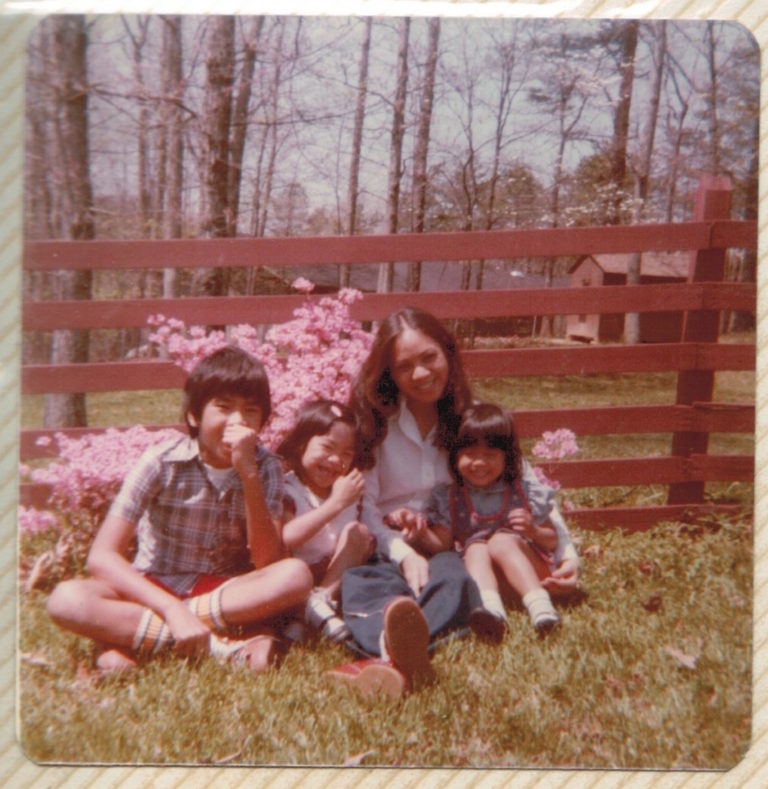

Image by Leo Hidalgo/Flickr, Attribution-NonCommercial.

Afflicting the Comfortable

In professor and poverty expert C. Nicole Mason’s new memoir, Born Bright: A Young Girl’s Journey From Nothing to Something in America, Mason tells the harrowing tale of how she deftly navigated the violence of structural poverty and systemic racism in Southern California in the ‘80s and ‘90s to end up in college. Like Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes or Jeanette Walls’ The Glass Castle, it makes painfully vivid what often happens under the radar: a child weathering the dysfunction of the adult world in the most courageous and innovative of ways.

Mason’s aim with her beautifully written memoir was not to formalize her particular victimization, but, in contrast, to point out just how ordinary the kind of challenges she faced were, and how lucky, not exceptional, she is to have survived them. She went to multiple failing schools, often missing more days than she attended. She was sometimes hungry and surrounded by drugs and violence from an early age. She was sexually abused by her stepfather and emotionally abandoned by her mother. She had no support when it came to applying to college — not just financially, but logistically. The fact that she ended up at Howard University is something of a miracle, actually.

As I was reading, I kept thinking about the radical nature of her underlying thesis: that she is not exceptional, just lucky, that her existence should not be held up as evidence of the so-called post-racial world, but as an anomaly in a country where poor kids’ chances at a stable life are decimated by substandard schools, a racist, classist justice system, wounded, violent caregivers, and financial instability perpetuated by lack of access to decent jobs or fair financial services.

The detail with which she writes about the indignities of being a poor kid brings the abstraction of poverty into focus:

On the way to school, we stopped halfway down the block to pick up a little girl who lived on the opposite side of the street from us. We arrived early and stood in the doorway as she ate Trix cereal and giggled at cartoons. The slurp of the milk and the crunch of the cereal were so familiar. My eyes tracked the motion of the spoon in her hand, from the bowl to her mouth. I desperately wanted some.

“Do y’all want a bowl?” the girl’s mother asked. I had been caught staring.

Before Amber could open her mouth to say yes, I answered no for the both of us.

C. Nicole Mason survived that hungry tummy, that pride, and so many other heavy crosses no tiny human should bear, but her survival is not reason for us to have faith in the inevitable march of progress for all. To the contrary, she recounts every painful detail in her new book (one that I can imagine being canonized) so that we might lose faith in that inevitability, so that we might question, once again, the accuracy of our own sight, the universality of our relative comfort.

Reading Born Bright was an exercise of bearing witness for me. In part, I was bearing witness to her: one real girl, trying to read the signs and symbols around her, craving more attention and access, mentoring herself where there were no mentors, leveraging the hell out of the supports that did come along (a helpful guidance counselor, for one). This was so important because too often poor kids are statistics to those of us who don’t know or interact with them. By investing in reading the story of one little girl, I was investing in my own capacity to look deeper than headlines.

In part, I was bearing witness to myself. Where I recoiled in shock, I took notice; clearly my reality is deeply disconnected from the one that this little girl lived and that’s important for me to register. Where I cringed at the adult behavior around her, I took notice; I asked myself to look at the wounds underneath that kind of violence, particularly when it came to her mother, who I must admit I felt a lot of anger towards. At first I asked, “Why isn’t she showing up for her little girl? Why doesn’t she believe her?” But then I asked, “Who didn’t show up for her?”

Finley Peter Dunne, an American humorist, once wrote that a journalist’s job is to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” That’s what Mason has done. She’s used the revealing details of her own ordinary life to wake me — wake us — up to an extraordinary truth: that we claim to be an ethical people while still tolerating, daily, the abuse and neglect of thousands of children based solely on the zip codes and families they were born into.

In this country, we tend to focus on what Booker T. Washington famously dubbed “the talented tenth” — the black kids who make it out of poverty and into fancy schools, the ones who end up with prestigious jobs and the capacity to blend into white, elite worlds. That’s far more comfortable than looking at the persistent plague of poverty because it jives perfectly with our American Dream ethos. It makes us feel less complicit. If Barack Obama and Condoleezza Rice exist, then, we reason, the legacies of slavery must be surmountable, maybe even fading. If Oprah and Robert F. Smith exist, then anyone has a chance at winning the life lottery even while racism persists.

While this may soothe the psyche, it’s morally repugnant.

As I turn the last page, I look up at my own three-year-old and two-month-old and wonder how I can make my own parenting less narcissistic. White, upper-middle-class parents in particular are led to believe that it is normal, even necessary, to spend our energy mostly thinking about how to make sure that our kids get the best of everything: the best food, the best schools, the best childcare. But what of the kids who aren’t related to us, who don’t look like us? What do I teach my girls if I model that my every waking second is directed towards improving their lives?

How can I parent like a reader? How can I parent like a witness? How can I parent like a citizen?

Share your reflection