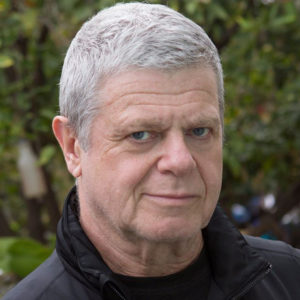

Gustavo Santaolalla

How Movie Music Moves Us

Movies, for some of us, are a form of modern church. The Argentinian composer and musician Gustavo Santaolalla creates cinematic landscapes — movie soundtracks that become soundtracks for life. He’s won back-to-back Academy Awards for his original scores for Brokeback Mountain and Babel. We experience his humanity and creative philosophy behind a kind of music that moves us like no other.

Guest

Gustavo Santaolalla has composed film scores for over a dozen features including Amores Perros, The Motorcycle Diaries, Brokeback Mountain, Babel, On the Road, and Wild Tales. He also composed the opening score for the hit Netflix series Making of a Murderer. His latest solo album is called Camino. In 2015 he was inducted into the Latin Songwriters Hall of Fame.

Transcript

August 25, 2016

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Soundtracks of movies become soundtracks of our culture. Movies, for some of us, are a form of modern church. So though you may not immediately recognize the name Gustavo Santaolalla, you’ve probably heard the cinematic landscapes he’s created for films like Babel and Brokeback Mountain, for which he’s won Academy Awards. This is the opening track from the film The Motorcycle Diaries. We experience Gustavo Santaolalla’s human and creative philosophy behind a kind of music that moves us like no other.

MR. GUSTAVO SANTAOLALLA: I, in general, like not to have too much music in the movies. I like the music to become relevant at certain points. When you have a really dramatic scene or when something is really happening on the screen, why would you put some music to it? I mean, you can turn something dramatic into something melodramatic very easily.

[music: “Apertura” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Apertura” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: Gustavo Santaolalla grew up in Argentina in the time of the military junta and the trauma that became known as the Dirty War. After moving to Los Angeles, he became a record producer, a sometime solo performer, and he’s composed the scores for over a dozen feature films. In all of this, he sustains a creative tension between his Argentinian identity and the global contours of modern film and modern life. I spoke with him in 2015, the year he was inducted into the Latin Songwriters Hall of Fame.

MS. TIPPETT: So tell me, just as we begin, how would you describe the spiritual background of your childhood, however you understand that now?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Absolutely. I was raised in the province of Buenos Aires. I wasn’t raised in the city. I was probably, like, an hour away from the city in a very bucolic place — I mean, dirt roads and birds and insects and gardens and wonderful trees. My parents were Catholic. I mean, my mom is still Catholic. My dad passed away when I was young. And I was raised Catholic. And so I always found a connection between music and kind of that spiritual life that came to me, basically, through me going to church and what I was learning there. I started playing guitar when I was 5 years old.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So it was a very early age. And I could really connect the music and that art to my spirit. And I was an altar boy. I mean, I did all the things. And I was very interested in the church, actually. I thought of becoming a priest when I was a little kid. But by the time I was 11, I went into a spiritual crisis…

MS. TIPPETT: I’d say that’s young for a spiritual crisis. You were a prodigy in your spiritual crisis. [laughs]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: [laughs] Well. And so I went to the priest and told him my questions. And they called my parents, and they — I don’t know. I think they’d been planning to exorcise me or something. And my father, who was an amazing guy, just told me, “Listen, if you don’t feel it anymore, you shouldn’t do it.” And that was it. I was never called upon that subject anymore by my parents, and they just let me continue with my own search, which I still do until this day. And then I went into different searches in my life. I actually lived in a commune between 18 and 24, and I led a pretty monastic life. I mean, we’re talking about years — the hippie years and other type of also of communes. But we…

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve seen that described as a yogic commune that you were in.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Absolutely. Yes, and we did comparative studies of religion.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: It was a great — yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And you were a band, right? But you were…

MR. SANTAOLALLA: We were in a big band, but the band I was — for a while there — number one.

MS. TIPPETT: And I see that — like a fusion of rock and Latin American folk.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Absolutely. Arco Iris was the name of the band, “Rainbow.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And so — but I led a truly monastic life. Not only, I mean, I didn’t do any drugs or alcohol. I didn’t drink — eat any meat. I mean, I was vegetarian in Argentina at a time where people looked at you like, “Is this guy OK? Is he sick? I mean, how can he not eat meat?” But also, I was celibate.

MS. TIPPETT: Really.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I mean, all those years. Yes. Yes. I mean, in the pinnacle of success with my rock band, I practiced kundalini yoga and transmute my energy.

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And it was a great learning experience, and lots of stuff that I learned there I took with me for the rest of my life.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Let me just ask you about — so that was your first band when you were 16.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: But I’ve seen two interesting musical influences from your early life. And one of them is tango — that you grew up listening to tango just around the house.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And the other was The Beatles. [laughs]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Of course. Well, the Beatles are like my — of course I was listening to music before the Beatles came into our light. But really, they made the difference, and they were a guiding force and still are. I mean, I believe they’re kind of like my musical parents, you know? But tango — it was the music that was around the house, and it was around everywhere because you can hear tango on the buses or on the radio at home. My father used to sing every morning, meanwhile he shaved. He will sing tangos — he will stop the shaving to finish a phrase of a tango.

[music: “Chiqué” by Quinteto Baffa-De Lio]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So it was around me and part of sort of my sonic landscape since I was a kid. At the beginning, really, I didn’t get it when I was a kid. But when I became more and more involved, and I had my band, I always had tremendous respect for the musicians and for the genre. I mean, the genre is such an unbelievable style of music. I mean, it’s the style of music that can be so sophisticated and yet so popular.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. Both of those things at the same time.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: At the same time. Yeah. So I always was very, very respectful about it. And because I am a sort of an advocate of the concept of identity — and I always felt that it was very important for me to show who I am and where do I come from in everything that I do — I knew that at a certain point, tango was going to come into my life. I just had to wait. And I think, in my case, although there are some great young tango performers and artists involved with the culture — in my case, I think age played an important role. I think…

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean by that?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Well, I think tango taps into subjects in such a passionate — and with such a — experienced in life that you have to really have lived some time to really appreciate it. I always find very, almost I would say ridiculous — when you see a little kid on T.V. singing a tango, I just think that…

MS. TIPPETT: That they can’t get it? That they can’t possibly understand it?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: No. Because I think you need to have some true, heavy experiences. I mean, you have to have experienced life to be able to interpret properly that genre.

[music: “Vieja Viola” by Aníbal Arias Y Lágrima Ríos]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So in my case, it really worked that way. That’s when I decided to explore in the genre. And since I’m not an academically-trained musician, I don’t know how to read or write music. My way, really, to learn, is by doing it, playing it, or listening to it, or being close to somebody that is a master so I can learn something from that way. And so I did a project called Café de los maestros that involved, I think, the greatest tango players alive at the moment. Unfortunately, that project came out in 2005, and most of the people that participated on that are now gone. And so it was great to actually capture them still vital, still doing great music. And it was a very, very rewarding experience.

[music: “La Cumparsita” by Carlos Lázzari Y Orquesta]

MS. TIPPETT: This music is from that Café de los maestros album featuring legendary masters of tango from the 1940s and ‘50s. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. My guest, Gustavo Santaolalla, is best known in the U.S. for his Oscar-winning soundtracks to movies like Babel and Brokeback Mountain.

[music: “La Cumparsita” by Carlos Lázzari Y Orquesta]

MS. TIPPETT: I think what you just said about tango, that it holds depths of human experience — one thing that people experience in your music, and probably most people have experienced that through the music you’ve written for movies, Brokeback Mountain, Babel, or Motorcycle Diaries, is this scope of human experience. Laughter and joy and pain and heartbreak and loss — that all those things are there together. And I do want to ask you if you think that that was also informed by growing up in Argentina when you did. I mean, you talked about identity as this theme that runs throughout your life, and your spiritual search, and your music.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And I just wonder if you’d say a little bit more about that root of your own identity.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yeah. I think there’s a combination of many things. I mean, as I grew older and did more — lots of times I’ve been able to articulate things years after I’ve played them.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: For example, now I can talk about my use of silence and space in the music. But it was totally something that was unconscious. And that was the way I heard that it should be played, not that it was something that I was doing on purpose or there was a logistic behind that decision. It was very intuitive, just like everything that I do.

MS. TIPPETT: Can you…

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I think — yes?

MS. TIPPETT: Can you think about something you wrote or — where you observed the silence or space later on? A piece of music?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I think Brokeback Mountain is a great example, you know?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Like some of those — the first theme that plays when the movie opens.

[music: “Opening” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: [sings] So, there’s all those spaces. I mean, I love that moment where you’re kind of suspended. And it’s not the silence that occurs at the very end of a tune, but it’s the silence that occurs between two notes. I like to think that playing a lot of notes is something that is easier to achieve. You just practice a lot, and you get to play a lot of notes. Not playing, it’s a little bit more difficult sometimes, you know?

[music: “Opening” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Going back to the subject of identity, I feel that there’s a point that — even all of those influences — I mean, obviously they come to play a role, but then there’s something more deep that really relates to who you are as a human being and obviously that all those elements, those cultural elements — your upbringing — all of that plays a role. But there is something that comes from within and that connects to something that I don’t understand. Any artist that is really honest, I think, will agree that there’s a point that you don’t really know who is doing what you’re doing. I mean, you are doing it, but there’s something, there’s a connection with something else that is beyond your understanding. And finding who you are in that connection, that’s another deeper part of your identity that I’m working on now.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. That’s really interesting, and it’s also something that’s really hard to talk about, right? To put words around?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Absolutely. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Because I hear you — you’re talking about something relational, and whether you want to call that God or…

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes, I don’t like — I mean, I’m kind of like an agnostic now. I do feel that there is something that is bigger and stronger than me, than each one of these elements that we are part of.

MS. TIPPETT: And that somehow that’s in the creative process — that you experience that through the creative process.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I believe so. I believe so. It’s something that is really beyond me. And I think, because of the connection with heart, with feelings, it’s not something that is just neurological. But I feel that whatever I do has to be connected with the heart. As much as rational as I can put into something and say, “I’m going to use this instrument,” or, “For this movie, I believe this.” That it’s part of rationalizing what I’m going to do. The moment that I’m creating, and then I’m there confronted with whatever comes out of my hands or whatever I am playing, it’s something really that connects with my heart.

[music: “Pampa” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: I feel like there’s also — there’s very much, in your musical career, this transcending boundaries of identity. I mean, certainly geographic and cultural, right? And again, it’s all through your musical career. It’s certainly there in the scores you’ve done for movies. Brokeback Mountain could not be more American. Babel had this Middle Eastern component. Motorcycle Diaries — Latin America. And it seems like that is a special part of your kind of inspiration. How does that fit into kind of your — I don’t know — philosophy of music or what music can do?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Well, I do believe that part of — you have an identity. The first identity is related probably to your family.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Then you have an identity with your block, the block that you live in, then your neighborhood, then the city, then the country, then the region of the world, and then finally the world. There is an identity of us planetary beings. And specifically, also in those examples, Brokeback Mountain and Babel and Motorcycle Diaries, I did want to obviously express in the music the backdrop that this music was set up against. But at the same time, I wanted to give it a universal feeling, I think.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: In Brokeback Mountain, for example, I know that there is an influence of Atahualpa Yupanqui, who was an amazing guitar player and singer-songwriter from Argentina. Probably nobody knows this, but I know that there is an influence. And I’m pretty sure if somebody from Texas would have done the music, it would have been different, you know? And yet it, it fit. The music, it fit. And nobody said, “Oh, this sounds like — this doesn’t sound like music that could be in an Americana movie.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: It fits, but yet, it has that, for me, that global component that I also like to feel that I have in my — that sort of universal feeling to it. No matter if it’s tinted with South American flavor or with an Americana flavor or with a Middle Eastern flavor, it still has a universal appeal.

[music: “The Wings” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: When you talked a minute ago about the different layers of identity that pertain to all of us, from the very personal to the global, I think, even though in the 21st century we live in a globalized world where our fate is tied in very concrete ways to people across the globe, that heart connection to that reality is not always easy to muster, right? We haven’t all made that leap in our minds and hearts.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I’m sorry, you said our fate is connected?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, our fate. I mean, we genuinely are tied to the fate of people around the world.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: We’re all connected.

MS. TIPPETT: But we don’t always — it can also be an abstraction. And it seems to me that through music, you actually have access to that, to those overlapping identities in a way that…

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I agree with you because I think music is a different art form. I’ve been told this by some of these great directors that I had the opportunity to work with. And not just one of them, but it was three of them, the great ones: Alejandro González Iñárritu, Walter Salles and Ang Lee. They manifested how sometimes they feel envy about a musician because, for their art, there’s so many steps involved in the process of making a film, from getting the camera, and shooting a scene, and editing, and looking at it. And whereas you grab a guitar, and you can just create a moment, and then it goes. Boom, that’s it. If you play something live, you will play it and — where did it go? But it could evoke, in that moment, all kinds of emotions. I think music has that — it’s embedded in the DNA of music is this universal connection. It is part of what music has that I don’t think all arts have.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. You’ve told a story about when you were doing the score for Babel. You said you were looking for an instrument that worked as a connector. And you didn’t want it to end up sounding like it was a National Geographic documentary.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Correct.

MS. TIPPETT: Right? Tell that story because I think that’s a great example of also how you’re not doing this in a linear, simplistic way.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes, because an instrument can be a great storyteller. And I thought about it for Babel specifically because the film takes place in three different locations: in Africa, in Southern California, in Mexico, Mexican border, and in Japan. So I found in the oud, that instrument. And the oud is the ancestor of the lute, therefore the ancestor of the guitar, something very related to me personally. So the oud was perfect for this Arabic feel that I wanted to have in the Moroccan part of the film. But although, I don’t play the oud like a traditional oud player because they play with a plectrum. I play with my fingers. It’s a totally different groove. But it still is the instrument. I didn’t want it to sound 100 percent truly folkloric from that part. I just wanted to evoke that feeling. And that instrument, because it was an ancestor of the guitar and connected to the guitar, for me, was perfect for Mexico…

[music: “Bus Ride” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: Right, because it has kind of tentacles to these other cultures then.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Of course. And it had a resonance, especially when I played it the way I played it, with a koto, which is a string instrument from Japan. So I found that this instrument could connect the stories and it was a great helper for me.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s this line, I think, you’ve said is an Argentinian idea that — “Paint your little village, and you will be painting the world.”

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Mm-hmm. I think that’s what we’ve been talking about.

[music: “Two Worlds, One Heart” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this show with Gustavo Santaolalla through our website, onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “The Book of Life Theme 2” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a conversation with the Argentinian film composer and musician, Gustavo Santaolalla. He often brings the ronroco, a small Andean instrument from the mandolin family, into his music and his award-winning film scores for Brokeback Mountain and Babel. This is him playing the ronroco and the guitar in his score for the animated film, The Book of Life.

[music: “The Book of Life Theme 2” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: Gustavo Santaolalla is based in Los Angeles, but he grew up making music as the Dirty War began in Argentina, in which so many people disappeared at the hands of a military junta. He’s remained steeped in a Latin American sensibility even as he scores films that evoke the global contours of modern life.

MS. TIPPETT: I wanted to ask you about what you’ve learned about how music works with movies and in movies to deepen and complete that experience. But I’m wondering, as I’m listening to you speak, whether, in fact, the music in movies is part of what draws us on an emotional level into that, makes this experience that we’re watching — the story — connect on another level to our own internal lives.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes. I’m going to talk from my own particular experience because there’s so many ways to tap into this, and there’s people that do a different type of work and still is amazing, people that work with huge orchestras and with movies that have music and music and music and music. I mean, I’ve done some of that too, but in general, my approach has been always more minimal and with a discreet use of music. I find that music in movies — I, in general, like not to have too much music in the movies. I like the music to become relevant at certain points. When you have a really dramatic scene or when something is really happening on the screen, why would you put some music too it, you know? You can turn something dramatic into something melodramatic very easily.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I find that also very disturbing sometimes in documentaries when you have something that is a very strong reality or a very…

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And you put music to it, and then it kind of trivializes what you’re seeing.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, it can almost emotionally manipulative.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Exactly. So I always like to be more discreet with the music to try to let the scene finish and then come in with the music to kind of support and let you as a spectator emotionally get that scene sink into you by the help of the music — but once that scene is done. So I really dislike when I see — I mean, I could picture myself watching a director and editor in a room looking at a scene that is not working and saying, “Let’s put some music.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: “Let’s see if we can solve this with the music.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And I just don’t like that, and I see that a lot.

MS. TIPPETT: But also, I was really intrigued to learn that you — do you always write the music before the film is shot?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I don’t, but that’s my favorite way of working.

MS. TIPPETT: But that’s so surprising, I think, to an outsider. I mean, one would never imagine that’s even possible.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Well, the biggest example of that is Brokeback. I did the whole score of that movie just from the script and one meeting with Ang Lee.

MS. TIPPETT: Really?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Before they shot one frame. And obviously it was the genius of Ang Lee to say, “We’re going to put this piece here. We’re going to put here, this. We’re going to repeat it here.” But he had — by the moment he sat down to edit the film, he had a basket full of music that was inspired by the story, the characters, and by talking to him just once. But I had a great meeting with him.

I like to work that way, more in an abstract — and then obviously, adjusted to a particular scene or edited to the image or work, and if you need to extend a part or something. But the themes, the mood of the music of the film, I like to do it that way. And I feel like — for example, Ang will listen to the music during the shooting and play the music to the actors. I know Alejandro González Iñárritu, in some of the hospital scenes in 21 Grams, he played the music on the set because he was going to replace the sound anyhow.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, isn’t that interesting? Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So he could kind of create a mood by playing the music. And so I think the music also becomes kind of a part of the fabric of the film in a different way.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, rather than an accompaniment, it’s part of the fabric.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And usually, I have to say, in the way that the industry works is that the musician or the composer comes at the very end when the movie is already edited with some temp music, which is music from other people, from other movies. And then the composer kind of has to chase that temp. And it’s not really very creative to be honest.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I just don’t like to work that way. I don’t do many films. I am very, very picky about selecting the films that I get involved with. But I feel very proud of them, and I like the way that I’ve been able to work in them.

[music: “Roman Candles” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: I saw online a really interesting conversation that you were part of with John Williams. And you brought up the subject of the music in Psycho and in Jaws, which of course he did.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Well, he didn’t do Psycho.

MS. TIPPETT: No, no. Jaws. Right. Jaws.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Jaws. Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And just say a little bit more about what you hear happening in those two pieces of music — or just choose one of them — what it is and how that’s composed and played, how that’s hooking into the human psyche. [laughs]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Well, I think — I mean, the element of obsessiveness the choice of timbres being — low brass that John used or the ones that are used in Psycho, which are really high strings, by Bernard Herrmann. And something that connects, I think, with a heartbeat in a way — how when we get anxious, our heartbeat kind of accelerates.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: There’s a connection with that anxiety. It produces, not only tension, but anxiety.

[music: “Main Title/First Victim” by John Williams & Orchestra and “The Knife” by Bernard Herrmann]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I think that that’s really interesting about those two pieces that because tension — there’s a lot of pieces that create tension. But these pieces not only create tension; they create a high level of anxiety.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I mean, they mastered it. There’s other pieces in history, but I think those two are iconic.

[music: “Main Title/First Victim” by John Williams & Orchestra and “The Knife” by Bernard Herrmann]

MS. TIPPETT: To go a little bit deeper with that, I feel like for you, from a very early age and all the way through your life with music, you live with a conviction that music has the power to transform people, that it is a transformative medium. And I wonder if you could say — what does music work in us that makes it transformative when it is?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: First of all, I think anything that steers your emotions have the potential to transform you.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And I think music has that power. It’s something that really — even if it’s something that we can’t necessarily articulate, there is a process, for me, of — when you are confronted with a work of art and with a great piece of music — of learning something different about the world, about life, about yourself. And I think that transforms you.

MS. TIPPETT: You often speak of yourself as an artist, not a musician, an artist who works with music. And you’ve also said that art is a way of reorganizing reality.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yeah. When you think about music — the scale. It’s twelve notes. I mean, seven notes with the semi-tones and stuff. Basically, it’s the way I organize those notes that will be my melody. And the way the other guy will organize those will be his melody. And the way you organize three notes, it will be a chord, or four notes, a chord. And so a painter that decides that he interprets a sunset in a particular way. But it’s really putting reality — a peculiar way of looking at reality. It’s reorganizing it in a very peculiar way. That peculiar way is what gives you the tag, the brand. It’s like Picasso. He has a particular way of reorganizing reality and the vision of reality, his vision of reality.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And I think that’s what is so exciting. And it’s something, once again, that transform us and also exorcise us. Art has that possibility. So if somebody is feeling very sad and writes a piece of music, it’s a way of exorcising that and turning, transforming that sadness into something now, reorganizing those feelings in a way that are now materialized in a piece of music.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. That’s a form of transformation as well.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: You are more recently working on the soundtrack for a video game. And I want to ask you about that because, I mean, when I look — this is called The Last of Us. And when I looked up the description of it, it says “action-adventure survival horror video game.” [laughs] And it has the caution “blood and gore, intense violence, sexual themes, strong language.” [laughs]

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Absolutely. It’s all of the above. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: And I wonder how you think about — I sense that, for you, there’s a purposefulness in everything you do, in your music. And how do you think about the meaning or the transformation that’s happening with something like this video game? And granted, I’m giving you Wikipedia definition of it, and I have not really seen it. So I’m curious about your experience of that.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Well, the video game represented, for me, to start with a challenge, to do something in a different media that I never worked before. That was already very attractive to me. I’m not a gamer myself, but I have a 15-year-old son that is a gamer.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: All kinds of games. So I thought that this was fantastic. This was a game that, even if it has some of the elements and the codes that are related to these type of games, it really brought to the table a whole bunch of different things and spaces. And I’m very interested in that sort of virtual world. And I see it at home with my son and how it can be very distracting, in a way, but also can be very enjoyable and very useful in a certain sense because you have to develop certain abilities — como se dice, abilidades — certain skills.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: That are interesting strategies and logistics that make your brain work in a different way. Anything else — it should be done with moderation, right? [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: If not, you can become a zombie yourself, you know?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. That whole genre of action-adventure survival horror is everywhere, especially for these — for new generations. There’s something about this…

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Probably something that reflects the outside reality.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: It’s a way to put it together. It’s another way of reorganizing reality.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: [laughs] We live in a society that is, unfortunately, full of zombies and horror and awful things. And fortunately, we just can go into a console and take care of them.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s right. [laughs]

[music: “The Last of Us” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: This is from Gustavo Santaolalla’s score for the popular video game, The Last of Us. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. My guest, Gustavo Santaolalla, is best known in the U.S. for his movie soundtracks. He’s won two Academy awards for the scores for Babel and Brokeback Mountain.

[music: “The Last of Us” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: One thing we haven’t talked about yet is Motorcycle Diaries, which was about Che Guevara. And my colleague Lily, who’s Colombian, talks about how especially people in Latin America saw that and reacted to that. And just the question about your own identity which we talked about in the beginning as an Argentinian, as a Latin American, as a global citizen — just was that story, and was working with music with that story, meaningful for you in a special way?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: It was very meaningful because I will say that I come from that generation, where — all those moments were happening at the same time — at the same time that the Beatles were happening, Che Guevara was in full force. So I mean, lots of things. And Eastern philosophies were coming. And I come from that generation, so he’s a man that definitely has marked us. The fact also that he’s Argentinian, and the fact that he was a guy that, until the very end, stayed true to his beliefs. And he was a revolutionary. He was a guy that thought that it was necessary to implement the use of weapons to sometimes get what he viewed was a better world. I particularly loved working in Motorcycle Diaries because it tapped into a moment in his life in which he wasn’t still “Che.” He was Ernesto Guevara.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: He was a guy that became a doctor. And he wanted to really go out and look at the world. This is a time in the ‘50s and stuff — very related to also people like Kerouac and people that really wanted to go on that road to try to find answers for themselves. It was a self-discovery trip. And so that trip that he took with Granado was something that really, I think, kind of shaped and formed the “Che” to come. You know what I mean?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: All those experiences that he lived in those first trips marked him profoundly. I think like when you read the story of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, when he finally went out of the palace and went out to the outside world and looked at what was happening, he came back he was totally transformed. He knew he wanted to do something, you know? And I think of Ernesto in same way. I think that that was very important for him to decide what he was going to do and what he was going to devote the rest of his life.

[music: “Leaving Miramar” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve traveled a long way from your childhood in Argentina. You travelled a long way musically and geographically. You left, you’ve gone back. It seems to me that you’ve always thought about identity. It’s kind of been a theme through your life, and also had music as a source of spirit and meaning. And I wonder, what have you learned about — what do now that you that you didn’t know when you left Argentina at 24? What are some of the insights that have come with time and experience that you might not have guessed then?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: I mean, one of obviously transformative experience is having kids, to have children. And all of my children were born here in the United States. They’re bilingual, and they go to Argentina at least once a year, and they have travelled extensively. So they have that. I tend also for them to have that global quality. But I think that’s something definitely that, when I came from Argentina, I didn’t know. And that’s something that obviously transforms you as a human being. It’s the biggest decentralizing factor that you can encounter in your life is having a kid. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] I like that. That’s a good way to put it.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So I learned, also, because I travel so much around the world, I kind of been able to support some of my ideas, the ideas that — we talked before that — how diverse we are and how similar we are. Because I’ve been around the world, and I had the opportunity to travel, not in all the world, but quite a bit of a road. I’ve been in big places like China, or India, or Japan, several times in Africa, and Europe, and Greece, and Turkey, and Israel. I think one of the reaffirming things that we always knew — I mean, in a way, I think everything that we learn is actually we’re relearning it.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Say some more.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: We already knew. We already knew, but now we are confronted with something, and we connect with the knowledge that we already have. And that’s part of the process of learning.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And so living in Argentina gave me a lot of that. I mean, I left Argentina in a really bad moment.

MS. TIPPETT: You left Argentina right as the Dirty War was starting, right?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yeah. In the middle of the Dirty War.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. In the middle. Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So, as you know, we have 30,000 people disappeared. It was really horrible, and we’re still suffering from that. I mean, we’re still — fortunately, in the last ten years, most of the people who have been involved in those heinous crimes have been brought to justice and put in jail — a lot of them — which didn’t happen before because they had amnesties and all these awful things that just — to get away with it. But now, most of them are in jail. But we still feel the repercussions of what happened. I mean, we have organizations like Madres de plaza de mayo and we have Abuelas de plaza de mayo, which — Abuelas is actually is an organization that is trying to identify and find grandkids of people that were disappeared.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: We know we have 500 of them, and we only have recouped like around 120 now. Recouped, precisely, that’s how they call it — finding their identity, finding who their parents were and what happened to them. And that’s basically — in some cases, some of those kids have been raised by nice families, and some kids have been raised by the same people that actually killed their parents.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So in that context, I came from Argentina to look at the world and realize why also these things happen, and how injustice goes rampant around the world, and what can I do to make a difference? And how can the work that you do affect people and transform people like what we were talking before. I think it is very important. And with all — the other thing that also I learned — and I think time was very helpful — is how to deal with these great recognitions that you can get through your career.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: And how can you put that in context and realize that, actually, the awards are never given to you as a person. They’re given to your work, to start with.

MS. TIPPETT: And internalizing that distinction.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: Yes, and your work is not only the fruit of your job. So that’s one. And the other one is that, usually when you’re there in the podium getting an award and stuff, that’s also the culmination of a phase or a work that involved other people, not only yourself.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: So I mean, I think all of those things I learned with time and age. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. So let me just ask you this big question. In some ways, we’ve been talking about this the whole time, but this life you’ve lived, where you were born, where you’ve gone, and your life in music, how do you think that’s formed your sense of what it means to be human? How do you think about that question?

MR. SANTAOLALLA: It’s a funny thing because I felt that I had control of my life. And I do have control of my life. But at the same time, I’m very aware that I don’t. I think this is something that happens to everybody. But I’ve been also proved so many times that something else was, coincidences, whatever it is, but situations that actually I didn’t have anything to — or something to do, but not really any logistics behind, you know?

The way I came into making music for movies, for example. I’ve always been told that my music was very visual, but my first coming really to some type of recognition was because I did the music for Amores Perros. And I almost didn’t do that music because I was so busy making records at the time. I never saw a script. I never saw a rough cut. And it was Alejandro’s first — was a first-time director. And I was so busy, I said — tomorrow — called and say, “Please, I’m not going to be able to do this.” I’m in the middle of the night, I woke up, and I start thinking, “What if this guy is a genius?” So that’s how that happened. He turned me onto Walter Salles. And suddenly, I was doing Motorcycle Diaries, and suddenly when we present Motorcycle Diaries at Sundance, I was doing Brokeback Mountain. And I remember the first time I was nominated for a Grammy, I lost. I thought, this is it. This my career.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. SANTAOLALLA: This was my big opportunity, and I missed it. And then life proved me differently. And so I’m very — in a way, I try to control what I do. But at the same time, I like to dance with whatever rhythm life proposes to me.

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] OK.

[music: “Cordon de Plata” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: Gustavo Santaolalla has composed film scores for over a dozen features including Amores Perros, The Motorcycle Diaries, Brokeback Mountain, Babel, On the Road, and Wild Tales. He also composed the opening score for the hit Netflix series Making of a Murderer. His latest solo album is called Camino.

[music: “Cordon de Plata” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: In case you missed it, we launched a shorter form podcast this year — Becoming Wise — vignettes in the mystery and art of living. These are sharable, 7-12 minute dips into wise and luminous lives and nourishing ideas urgent for our time – people like Brene Brown, Elie Wiesel, Seth Godin, and Maria Popova. And you can download all 20 episodes from the inaugural season right now, wherever podcasts are found.

[music: “Un Cielo para Los Dos” by Lágrima Ríos with Gustavo Santaolalla]

STAFF: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Annie Parsons, Marie Sambilay, Bethanie Kloecker, Selena Carlson, Dupe Oyebolu and Ariana Nedelman.

MS. TIPPETT: On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners are:

The Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the front lines of social change worldwide, at Fordfoundation.org.

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build a spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined

And, the Osprey Foundation – a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

![Cover of Babel (Gustavo Sanaolalla) [2 CD]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51bX8Wc-puL.jpg)

Reflections