Khaled Abou El Fadl and Harold M. Schulweis

Religion and Our World in Crisis

In this personal exchange between a Jewish rabbi and Islamic scholar, host Krista Tippett explores the integrity of religious faith and openness to the faiths of others. In a world in which religious experience is implicated in violence, two thinkers discuss how it is possible to love their own traditions and honor those of others.

This program was recorded live at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles in June 2003.

Image by David Monje/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

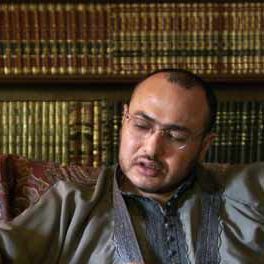

Khaled Abou El Fadl is Professor of Law at UCLA, and author of Tolerant Islam.

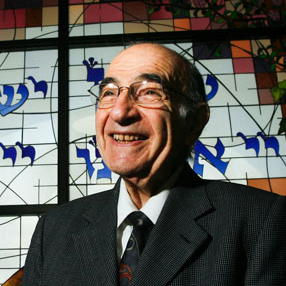

Harold M. Schulweis is senior rabbi of Valley Beth Shalom and founder of the Jewish Foundation for Rescuers.

Transcript

June 9, 2005

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I spoke with two men steeped in the ancient and modern dynamics of their faiths. Harold Schulweis is senior rabbi and spiritual leader of Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, California, and the author of many books, including Evil and the Morality of God, and Finding Each Other in Judaism. Khaled Abou El Fadl is a professor of law at UCLA and a renowned scholar of Islam. His most recent book is Islam and the Challenge of Democracy. As always on Speaking of Faith, in this live discussion, neither guest was asked to pronounce on behalf of his religion for all Jews or all Muslims. Each spoke in the first person at the intersection of theology and his particular human experiences. I began by turning to Khaled Abou El Fadl. In the years following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Egyptian-born Abou El Fadl has been hailed as one of the most daring contemporary Muslim voices. He has spoken out at personal risk, criticizing expressions of his own tradition that offend his understanding of Islamic faith. I wanted to draw him out on the Islamic ideas and values that give him sustenance and hope. Abou El Fadl says Islam can reclaim the best of its own tradition and work to support peace and tolerance by recovering its core moral value often overlooked in political discussions. The key to the future of his Islam, he says, lies in recovering the moral value of beauty. I asked Khaled Abou El Fadl what he means by that and why it matters to a world in crisis.

KHALED ABOU EL FADL: I think I would have to start by saying that beauty is to fall in love with God, to fall in love with the word of God, with the Qur’an, to read it and to feel that it peels away layers of obfuscation that I have spent numerous times building around myself. Beauty is to look around me and fully understand and feel therein is God, in all what I see around me, and to understand my place in this, that I am integral as God’s viceroy, as God’s agent on this earth, like everyone else is. And, at the same time, I am wonderfully irrelevant. And…

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean by that?

DR. EL FADL: That creation is much larger than me. I have been placed on this earth because I inherited the earth. It was entrusted to me by God. But at the same time, I don’t own it. I can’t own even a part of it. To experience these emotions — and I call them emotions — not at the level of philosophical thought, but to feel them, to vibrate with them, to sit in a room alone feeling utterly in the midst of companionship.

MS. TIPPETT: Like the presence of God, someone might say…

DR. EL FADL: The presence of God. And that to me is beauty.

MS. TIPPETT: You have written about this moral value of beauty in the context of essays about reclaiming the best of Islam, about addressing, you know, the problems of religion in the world, of, you know, terrorism. Make that connection for me.

DR. EL FADL: I have never seen God in an act of destructiveness, never. Qur’an talks about corrupting the earth and undoing what God has built. And, literally, the Qur’an talks about this reprehensible act, and that is corrupting the earth, and corruption is always taking what God has built, what God has created, and uncreating it, undoing it, dismantling it. And beauty is in this act of creation. And ugliness is in the act of uncreation, or the undoing of creation. And I’ve never seen beauty in destructiveness. And those who find God in terrorism, in all types of violence, there is something that in my universe, in my experience, something that has awfully gone wrong in the way they engage the objective manifestations of God.

MS. TIPPETT: I think when you use the word beauty, I’m also thinking goodness. What’s the Arabic word that you’re translating as beauty? I’m just curious.

DR. EL FADL: The word is jamal. There is a tradition that says God is beautiful and loves beauty. God describes God’s self in the text of the Qur’an consistently as the beautiful and gives hints as to what this beauty is. One of the extremely invigorating things for me was when God identifies God’s beauty, God’s own beauty, God talks about compassion, mercy, forgiveness, talks about the ability to balance, to understand the balance in a different context. And eventually, God willing, I am working on a philosophical text that explains what the conception of beauty that I advocate is, but I can tell you right now I will outgrow the experience of the text by the time I finish it.

MS. TIPPETT: Muslim legal scholar Khaled Abou El Fadl. Today on Speaking of Faith, a conversation with Abou El Fadl and Rabbi Harold Schulweis, recorded live at the Skirball Center in Los Angeles. Dr. Abou El Fadl has been describing his passion for beauty as a core moral value in Islam. I asked Rabbi Schulweis whether there was a corollary in his own Jewish vocabulary.

HAROLD SCHULWEIS: There is a concept called hadrat kodesh, which means the beauty of holiness. And that means that the beauty is not at all limited to forms and shapes, but in relationships to individuals and it ties into this notion of tikkun olam.

MS. TIPPETT: Repair the world. I didn’t say that, yes.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: The world is broken, and religion is responsible for part of that fragmentation, deeply responsible. I think it’s important for us to recognize we’re not living in an isolated world. First of all, that God did not create religion. God created a universe. And within that universe…

MS. TIPPETT: That — you know, let’s just pause with that.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s — God did not create religion.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: He did not create…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: For example, Adam was not Jewish.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. And neither was Abraham.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Eve was not a Muslim.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: It’s important to know this.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Because what it means is that God…

MS. TIPPETT: This is going back to the basics again.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: God doesn’t create religion but he creates a universe and within that universe, he creates this unique individual who is, indeed, beautiful in potentia, potentially tra — he has within him this image of God, which is capacity, potentiality to improve, to transform the world as it is. And from where did he create this clay? The midrash, which is the Jewish creative imaginative exegesis, said he created it not from the north or the east nor the west or the south, not from Mecca or Jerusalem or Washington. He created it out of black earth and white earth and red earth and yellow earth. And now the question is what is this human being going to do with shaping that world? So he didn’t create religion. But we create religion. And this is, it seems to me, our tremendous problem.

MS. TIPPETT: Now you were writing about the problem of evil, Evil and the Morality of God a few decades ago.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: That is now a word which has entered our public vocabulary, our political vocabulary, and I’m thinking that that’s not unrelated to what you just said about we’re here, what are we doing with being here?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Nothing is unrelated.

MS. TIPPETT: Nothing is unrelated. How have you been thinking about that concept theologically in recent years?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Well, in theological language, let me talk your language, as it were. As I understand Islam, Christianity and Judaism, in common, they are very wary of idolatry. And idolatry is the worship of a part as if it’s the whole. And every religion, it seems to me, if we’re going to be sharp and hard and honest about it, is guilty of that kind of idolatry. That idolatry says the truth is with me, exclusively, finally and absolutely, which means it’s not with you, which means that the world is now split and religion has helped split with its dichotomizing notion of the world between — the children of light, the children of darkness; Jacob vs. Esau; those who are saved and those who are damned; those who are elected, those who are rejected. Everybody knows that God loves me. Well, I was the first election. Oh, no, no, no. You were elected, but you were rejected. Ah, no, no, no. Because there is a later and latest revelation and love and that’s me. So like children, we struggle with each other, not recognizing a fundamental truth that in order to have that beauty that Khaled talks about, as I understand it, it’s a beauty of wholeness. And what we find in the facts of life, in a terrible, awful, history, is that religions have been divisive, have been fractionalizing, have been destructive, have been ugly. Ugly religion? How could that be? That is our struggle. So we need beauty. And beauty has within itself one thing, a tremendous capacity to embrace, not to leave out people. God is, after all, either the father of all of us or he’s the father of none of us. This I earnestly believe. This is this concept of oneness which Jews recite constantly. Notion: `Hear, O Israel, Lord our God, the Lord is one.’ Not one as opposed to two or one as opposed to three, but oneness in a sense that Khaled and I are, in fact, children of God. And I know that God wills lots of religions. That I’m convinced of.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, that is something that I found expressed in both of your writings is how at the heart of your tradition, and you are both steeped in your traditions, diversity is not just assumed but honored, and that’s not something we hear religious people talking about. I just want to read some verses from the Qur’an that you quote, Dr. Abou El Fadl. `If thy Lord had willed, he would have made humankind into a single nation, but they will not cease to be diverse for this God created them humankind.’ Or `In humankind, God has created you for male and female and made you into diverse nations and tribes so that you may come to know each other.’

DR. EL FADL: Well, the beginning of illumination for me was to utterly doubt my illumination. And this was really the start. There was some guy that I knew a long time ago and he was going out with a woman, and then someone was telling him, `She loves you.’ And then he said, `Yeah, I know.’ And I remember very distinctly that struck me that when a person believes they know they are loved, then it becomes a relationship of arrogance and possession. If you say about your wife or about your mother, `Yeah, she loves me,’ if that is the case with human beings, to what extent can you say, `I know that God loves me, I know that I am the chosen, the elected, the preferred, the saved’? And it seemed to me — this was when I was about 15 years old — it started looking increasingly that it was rather impolite towards God to assume so much. And for the first time — I had memorized the Qur’an as — as a child, and I memorized these verses that you quoted, and they just were part of what I memorized. It never struck me. But having started down this road of feeling embarrassed by God because I had become convinced that God loves me, it’s a contractual relationship, or that I’m entitled to it, because I’ve performed certain rituals, then I have it, and I can put it in my pocket and I can go about unto my merry way, and feeling how shameful that is. That’s when these verses, I think, struck me for the first time. It’s as if you have read something a million times, but then you come and you read it once and they take you by storm. And what caught my attention particularly, the end of this verse, `And for that, God created them.’ Now very…

MS. TIPPETT: `That they should come to know each other.’

DR. EL FADL: `That they should come…’ Now, it seems that destroying one another is rather inconsistent with knowing one another. The word in Arabic is ta’aruf (تعارف), as the Qur’an says. And to know one another. And ta’aruf just doesn’t mean that I’ve become acquainted with you passingly. It actually means that I know something about you in a real sense. So it is genuine knowledge. Now that for me is when my road or my journey towards skepticism with my fundamentalist friends really started. Because how am I constantly being told that the relationship is either to dominate or be dominated, either to have power or to be powerless when I am left with this heavy duty that I have to actually know those who are different. And even the Qur’an makes no exceptions for those you hate. And I must know those I hate? Now how am I going to do this if I’m very busy killing them?

MS. TIPPETT: Dr. Khaled Abou El Fadl, a renowned Muslim jurist and religious thinker. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, a conversation between Dr. Abou El Fadl and Rabbi Harold Schulweis.

Dr. Abou El Fadl has been talking about a passage in the Qur’an that he values, a teaching that God made nations diverse so that they may come to know each other. Steeped in the tradition of Jewish scholarship, Rabbi Schulweis extends this thought, saying that the Hebrew word for knowing is related to the word for loving.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: To know is to love and to love is to know. I want to just add one other thing. There’s a most remarkable parable, illustration, that’s used in the Talmud. The question is: How could it possibly be that 600,000 Israelites were on the bottom of a mountain when revelation took place, and God spoke with one voice to the entire group, but everyone was convinced that God addressed him or her individually? How could that be? And the answer that a Rabbi Levi gives is, `Because God appears like a mirror, and everyone looks into that mirror and, inevitably, a portion of his own self is reflected.’ But you have to understand that there are multiple visions, and you have to understand that there is no immaculate perception.

MS. TIPPETT: Immaculate perception. Right.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Everybody sees according to his particular history, according to his narrative. So what should be done? What should be done is we should find out from each other `What did you see?’ And when we gather together and form a collective kind of image, then you have a clearer picture as to what God is. So the mirror is one, but the reflections are many. The text is one, but the interpretations are many.

MS. TIPPETT: This matter of interpreting texts, religious texts are used in all kinds of violent ways. The Bible and the Qur’an have both — we can all think of examples. You say some really interesting things, Dr. Abou El Fadl, that the text — and you’re talking about sacred text — will “morally enrich the reader but only if the reader will morally enrich the text. The meaning of the religious text is not fixed simply by the literal meaning of its words but depends, too, on the moral construction given to it by the reader.” And now saying that, it seems so obvious, but it’s a very helpful way to think about how sacred texts are used.

DR. EL FADL: Well, I think that’s another part of this personal legacy that you encouraged us to, realizing that if I go to the text expecting the text, even sacred text, for the relationship to be one way from text to reader, it started striking me as a rather arrogant, lazy relationship. `I am being lazy. I am going to the text and say, “Load me on.”‘ And I don’t want to do much work in this dialectical engagement because I want the text to take over. And I know from other parts in the Qur’an repeatedly condemns those who are lazy. And I always thought, of course, lazy meant when my mother would tell me, `Get up and help me wash the dishes,’ or, you know. But there’s a far worse type of laziness, and that is making God nothing more than a crutch for the ego. And in order to avoid what I call in my writings `authoritarian act,’ when you go to the text, you expect the text to, in this lazy relationship, to load you on, to be a one-way dynamic, and you’ll be disappointed. You’ll be disappointed because the text is too honorable to serve and cater to lazy human beings. So what you end up doing then, you, in this authoritarian despotic act, you take the text and you force the text simply to mirror everything that you project onto the text. So the text becomes simply part of your ego, part of your array of tools that you use in pure self-service, exactly like a leg and arm and eye, even worse. And, again, this sense of shame before God, because once God becomes truly manifest in your life, it’s this relationship of embarrassment is the one that’s most distinctive in my mind. And I just exceedingly felt ashamed and embarrassed and that, `If I write a book and a reader does this with my book, I’d be pretty offended.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Yeah. Yeah, that’s a good point.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: The devil can quote scriptures, and if he knew enough Talmud, he would quote from Gemara, too. The truth of the matter is that what Khaled said is terribly important. And, fortunately, in our tradition, we have a written law — and I think this is true with you — as well as an oral law. And the oral law means `by community of interpretation.’ And that interpretation is not monolithic. If you look and open up a page of the Talmud — and I have a feeling that the same would be for the Sharia, Hadith — you will find constant wrangling as to what is the meaning of this? And both of these opinions, both the house of Shamai and the house of Hillel, are recorded. And the question that is asked is why do you want to record both of them? Because if you have a majority opinion, let the majority opinion be recorded, and let the minority opinion disappear. And the answer is you will never know whether, in the future, you will need that minority opinion. And so, according to one wonderful, creative, imaginative notion of the revelation, when Moses goes up to the mountain, he is taught 49 ways in which something is permissible and 49 ways in which that same thing is prohibited. And it’s not a contradiction. It is a recognition of the malleability and the reality of life and its complexity. What appeared to you to be ridiculous yesterday now takes on a new, profound relevance. So this, I think, is terribly important.

MS. TIPPETT: All right. But then to what extent are these texts at all authoritative, and how can we trust them as part of our common life as well?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: You can trust them, it seems to me — first of all, you have to do what Khaled talked about. You have to wrestle with it. You have to wrestle with your conscience.

MS. TIPPETT: And does that mean you don’t listen to anybody who’s quoting the text unless you believe they’ve wrestled with it?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Well, if that text that is quoted runs counter to your ethical sensibilities, you have to read it again…

MS. TIPPETT: For yourself.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: …and again and again because of the premise with which we both start. We start with the fact that the Bible wants peace, wants wholeness, wants love. And if you find a law or a verse that is going to introduce a hatred and violence, then you’re not reading it right. And you’ve got to read it again and again and again. And you’ve got to consult with other people to see to it. Because in my tradition, in the Jewish tradition, I know that there are many cases in which you have a verse in the Bible that is contested by the rabbis. There will be a verse that’s — well, take the `eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ And the rabbis say, `This is ridiculous. What do you mean an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth? How could you possibly implement that law?’ Supposing, for example, I knock your tooth out, which I would never do…

MS. TIPPETT: I hope.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: …and you would like to knock my tooth out. And supposing I am toothless, and what are you going to do? This is a kind of reductio ad absurdum in which you’re trying to say, `Wait a minute. Don’t read that text with a literal slavishness. It must mean something else,’ and thus is introduced into the law a notion of monetary compensation for damages, for pain, for unemployment, for medical repair, etc., etc. That’s the way in which people make that text live.

MS. TIPPETT: Rabbi Harold Schulweis in conversation with Muslim thinker and scholar Khaled Abou El Fadl. Their encounter was recorded live at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. After a short break, more from both of them. Go to our Web site, speakingoffaith.org, and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each program as well as previews and exclusive extras. While there, learn how to purchase MP3 downloads of each week’s program. That’s speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith from American Public Media, public radio’s conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, Religion and our World in Crisis, a profound exchange between Rabbi Harold Schulweis and Muslim thinker Khaled Abou El Fadl recorded live in Los Angeles. Jewish and Islamic traditions both incorporate the teachings of a central sacred text. Next in our conversation, Khaled Abou El Fadl described what he considers the authentic relationship between Muslims and the Qur’an.

DR. EL FADL: There is not just the text that you see. There is an intellect and a heart that engages the text, that becomes married with the text to produce a relationship. Now, if it is a slavish relationship of master and servant, you cannot have a relationship. I would argue systematically that what you have is a relationship, but it’s not a relationship of beauty because it is…

MS. TIPPETT: And you mean that master-slave would be the person reading the…

DR. EL FADL: Either the text is enslaved to the reader…

MS. TIPPETT: Or the other way around.

DR. EL FADL: …or the reader is enslaved to the text.

MS. TIPPETT: Is enslaved to some literal interpretation of the text.

DR. EL FADL: Why? Because I start out with the premise that since I assume that creation is beautiful, I also assume that creation should not be negated. And if God has created this extremely subtle, multilayered intellect, and God has created this extremely subtle and expansive heart, the heart, you know, intellect and heart and so on, and God has created the text, then I move on to say it is a fundamental imbalance and injustice either for the intellect or this heart to cancel out the text or for the text to cancel out the intellect. And the problem with slavish readings, the master-servant relationship, is that it cannot be undertaken without undoing part of God’s creation. So undoing, for instance, the intellect. And so you started a relationship by negating the most remarkable creation of God. How could that lead to beauty?

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Which is a fascinating way to come at this point that both of you make, and I think that this evening is a demonstration of it, the importance of our minds in faith and in religion as a constructive force. Rabbi Schulweis.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: It’s within the Bible. When I was a child, the first thing that made me fall in love with the Bible was Abraham’s criticism of God. I couldn’t fathom it. How dare a mortal, finite, fallible…’

MS. TIPPETT: What’s that moment?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: That’s the moment in which God decides to tell Abraham that he’s going to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah because they’re evil. And then Abraham says to God, `Shall the judge of all the earth not do justice? How can you possibly destroy the good and the evil at the same time?’ And Abraham then begins to negotiate with God. It’s a remarkable passage. `What if there are 50 people who are good?’ `OK, then we won’t destroy them.’ `How about 40?’ `How about 30?’ `How about 20?’ `How about 10?’ Now the remarkable thing about that text is not only that it’s early in the Bible, that it’s Abraham, who is the father of all the three traditions — of Christianity, Judaism and Islam — but that it’s not considered lese-majeste. It’s not considered to be treason. He is never chastised for it. On the contrary, he is praised for it because he has expressed within himself, through his intellect and morality, through his conscience, if you will, he is appealing to God in the name of God, and God loves that.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right. It’s this meeting of intellect and morality.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, another point that you make that feels important to me is that if a reader approaches sacred text with no moral commitment, they will find nothing there but — what do you say?–discreet, legalistic, technical insights. I mean, that’s also…

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Worse than that. If he reads the text by itself he will find some very ugly passages.

MS. TIPPETT: And this is what happens in our public life also when, I think, we take these sacred texts out of context and try to discuss them not in religious ways.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Not only out of cont — let me just point up a — from my point of view, the five books of Moses, which is the Torah, is not the last word, and that’s important to understand. It’s the first word, because after that you have a whole body of literature. Now, Khaled is a master in jurisprudence, so he knows in his tradition as I know in my tradition that after the Bible was written and closed, you now have the Mishnah, and you now have the Gemara, you have the Talmud. You have a variety of interpretation. And they never end because I give interpretations as part of that chain of continuity of questioning, interpreting and relating one verse with another verse and one authority with another authority until we finally come to the conclusion that these and these are the words of a living God. And that, it seems to me, is important, this, not to allow the Bible to become a desiccated, dry, literal piece of literature that is thrown down from above, in the old terms, and we accept it in an indolent fashion.

MS. TIPPETT: Rabbi and author Harold Schulweis. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, a conversation between Rabbi Schulweis and Muslim thinker Khaled Abou El Fadl recorded at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. We’re discussing how to love one’s own belief and honor that of others. Bill Davis, the CEO of Southern California Public Radio, presented questions from the audience.

BILL DAVIS: Since we’re speaking of creative tensions in religious identity, we’d like for both of you to address some fundamental messages in the respective religious texts that lend themselves to this tension. For example, in the Qur’an, the finality of Islam as a religion and Mohammed as prophet; and in Genesis, that God gave the land of Judea and Samaria to the Israelites or that Jews are the chosen people.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: You want to take that first, Khaled?

DR. EL FADL: No. Go ahead.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Well, let me put it this way. I would like — I would prefer a different vocabulary, not that we are the chosen people, any of us, but we are a choosing people. And we all choose, and we shape our concept of God and our understanding of the character of God in terms of our history, in terms of our insights, in terms of our intuition. But I certainly would reject the notion of chosenness. I honestly don’t believe that, because chosen is invariably — is associated with those who are rejected. And I could not fathom that notion. And, again, it reverts back to a kind of almost infantile sibling rivalry. Do we not think that God is big enough, large enough and loving enough to share that love and that compassion and that wisdom with all the peoples of the world? And this is where a larger platform — you’d have to have more than just two of us here. You’d have to have a Buddhist here. You’d have to have a Shintoist here. You’d have to enlarge it, and that enlargement, it seems to me, is what you mean by the grandeur and majesty of God and his beauty.

DR. EL FADL: I don’t know why, as a Muslim, I believe that the Qur’an is the last of the literal revelations of God. Why God chose to stop with the Qur’an and not send more and more books, I don’t know. And, frankly, it doesn’t concern me, it doesn’t trouble me because what I do know is that the so-called finality of the Qur’an is not the finality of either revelation or the divine. God doesn’t cease to speak to human beings simply because God has produced the last words or the words that God wants to produce. In the same way that I continue to engage my readers, even after I decide to finish, you know, a book and say, `OK, off to the publishers,’ it does not in any way mean that I’ve closed up the truth within the covers of my book and ended it there. And I think that those who understand the Qur’an as somehow coming in and locking in wisdom and saying, `OK, enough wisdom. We’ve got it now. Done,’ really missed the point, and they render so much of the majesty of God post-Qur’an irrelevant.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: One of the reporters asked God, `Since you wrote this Bible, have you written anything lately?’ Only a journalist would understand that. Mr. Davis: The next question is for both of you as well, and it is: Is it possible to address the root cause of discord between the three Abrahamic faiths?

MS. TIPPETT: A small question.

MR. DAVIS: It’s a small question, yes. And then an even smaller one: Is it possible that this discord can be erased?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: There’s a story about a man who looked through a window, and he saw people gyrating, flailing their hands and making all kinds of odd motions. And he came to the conclusion that he was looking into a madhouse, until a door opened and he walked into the room and he heard the music. And he realized that it was not a madhouse; they were dancing. But if we are deaf to the inner music of the other tradition, we will then see each other as mad people. When I first meet people of a different faith, a different catechism, I get to know the music and, therefore, the choreography. But we don’t do that. We look at each other from the outside. When you spoke originally, Khaled, about the beauty and about the emotion, the things that are not intellectual, we recognize that theology and dogma and catechism somehow or other hides from each other that depth, that human being. `Fear and trembling,’ all Muslims are scared, all Jews are scared, all Christians are frightened to death when they take a look at their lives. And at such a moment, it seems to me, they begin to understand the pulse of the other. And at that particular point, there’s a crack, and it’s not going to come from theological explanation. It’s going to come from the fact that the mosques have got to be opened, the churches have got to be opened, the synagogues have got to be opened. There has got to be an exchange between the people to understand that whole civilizational complex because once you know, you begin to love.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm. There’s that word again, knowing and loving.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Yes.

DR. EL FADL: In my own relationship with God, I don’t feel the need to negate or deny the other. I am filled with my relationship with God sufficiently that I don’t feel the need. I don’t feel that I can only feel bliss if others are denied it. And what strikes me is how often there are people who call themselves religious, but they have that need. For some reason, it’s as if they cannot enjoy the love of their love or their beloved unless they know that others are not loved. And it’s a childish and egotistical and ugly emotion that you need to know others are not loved. The Qur’an and the mention of fear and trembling — one of the verses in the Qur’an — and actually it’s repeated in the Qur’an about three times; it’s a verse that deserves a lot of reflection, and it has not been sufficiently reflected upon and engaged, in this dynamic — is one that talks about other people or faiths. And it says something to the effect, `After Jews and Christians and those who do good,’ and it goes on to explain that those who do good means do justice, `they will have their reward.’ But it goes on to say, `And they shall not fear.’ And many people go looking in the Qur’an for verses that tell them that everyone has to be Muslim without bothering with, `What does, really, Muslim mean in the first place? What does it mean to be in a relationship of some mission to God?’ But that everyone has to be theologically, technocratically Muslim. Otherwise they are not comforted. The thing that always strikes me is that, exactly the point that the rabbi was explaining, is that this fear and trembling is a part that we spend so much of our lives egotistically denying and putting on airs. We’re too macho, we’re too brave to admit to what extent we are insecure and anxious and afraid. And the Qur’an comes in and sends this message of assurance, this message of comfort from that. So to answer the question, I think much can be explained by thinking about exactly the element of anxiety, longing and fear as to why you will find Christians, Jews and Muslims often at each other’s necks when it need not be.

MS. TIPPETT: Does it matter that we’re having this conversation tonight? I mean, is this just a drop in the bucket of thousands of years of discord in a world that’s in terrible trouble?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: I think it’s important for preachers and teachers and scholars not only to read the right scripture. For example, I want your listening audience to remember, to look at Isaiah Chapter 19. You’re not going to find it quoted very often, but it’s one of the most important verses. It says, `Blessed be Egypt, my people, and Assyria, the work of my hands, and Israel, mine inheritance.’ That’s Isaiah 19. I want them also, I think that this is the obligation of preachers and teachers and scholars, to be able to cite the tremendous reservoir of beauty from our tradition. For example, in one of a great rabbinic texts, it says, `I call heaven and earth to witness that whether it be male or female, whether it be servant or master, whether it be Jew or gentile, the Holy Spirit resides in everyone according to his deeds.’ This is important. Malachi is important: `Why is that not heard? Have we not all one father? Has not one God created all of us? Why do we deal treacherously, one with the other?’ So we come from the huge tradition that it has to be lifted up and raised. And I must say that this has been, for me, a wonderful experience. I have not met Khaled before, but he speaks my language. I understand him. He would be welcome in my shul.

MS. TIPPETT: Do we have some more questions? Mr. Davis: I thought I’d finish with this one question, which is: How do each of you express your love for God each day?

RABBI SCHULWEIS: I think I can only express my love of God through love of his creation. And if I hate his creatures, it’s like hating his children, can’t love him.

MS. TIPPETT: I think you just took us back to beauty, where we started.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Yes.

DR. EL FADL: We try to capture in a word, or, you know, we say God, we say Allah, we say whatever other word. But it is beyond language, and it’s something that those who have experienced can attest to it, but those who have not are puzzled by it. I celebrate that love in living and in my ecstasy in seeing life. I do not engage in a lot of activity that other people enjoy. But I, for instance, I can’t ever imagine myself going skiing or something like that…

MS. TIPPETT: The way you say that, skiing.

Mr. El Fadl: …or just the physical constitution is not there, the temperament is not there. The — or playing some, you know, hard American football. But the joy in watching all of that, in honoring it is overwhelming, and it’s an overwhelming passion and an overwhelming truth.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s so many places we could go with this conversation, and I think that’s probably the mark of a good conversation, that it leaves you thinking and it leaves you with more to talk about. I think what I value is we’ve named the fact that religion creates so many problems. We’ve also named the fact that God didn’t invent religion. That may be the great idea of the night. And the differences between you, you know, the distinctive ways that you live in your traditions and that your traditions speak to these questions is also important. And I think what we’re speaking to are religious ways at healing some of the trouble that religion causes and, also, some of what religion is supposed to be doing in the world.

RABBI SCHULWEIS: Share with you, maybe for me, a parting thought. There was a famous rabbi of the 18th century who said he could never understand, truly, Leviticus 19:18, `Love thy neighbor as thyself,’ until he went to a tavern, a bar, and he heard two peasants talking to each other. And one peasant said to the other, `Do you love me?’ A little inebriated. And the other said, `Of course I love you.’ `Well, if you really love me, where does it hurt me?’ And the other said, `I don’t know where it hurts you.’ `Well, you don’t love me. If you loved me, you would know where it hurts.’ And the other replied, `If you loved me, you’d tell me where it hurts.’ One of the remarkable things about such a meeting, which I hope would be done in many places, many venues, is the fact that we find where it hurts. We are obliged to do whatever we can to alleviate that hurt, and that is what dialogue is.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to thank both of you so much, and thanks to all of you for coming.

[Applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Harold Schulweis is senior rabbi and spiritual leader at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, California, and the author of many books, including Finding Each Other in Judaism. Khaled Abou El Fadl is professor of law at the UCLA School of Law. His most recent book is Islam and the Challenge of Democracy.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this program. Please contact us through our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. There, learn how to purchase MP3 downloads of each week’s program and sign up for our free weekly e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each week’s program as well as previews and exclusive extras. That’s speakingoffaith.org. This program was produced by Mitch Hanley, Kate Moos, Brian Newhouse, Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss. Special thanks to Bill Davis, KPCC and the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. We say a fond farewell this week to Marge Ostroushko. She has been with us from the beginning. Her great energy, spirit and experience will remain at the heart of this program, and we will miss her. The executive producer of Speaking of Faith is Bill Buzenberg. I’m Krista Tippett. Next week, an exploration of the ethics and the inner life of dying in America. Please join us.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections