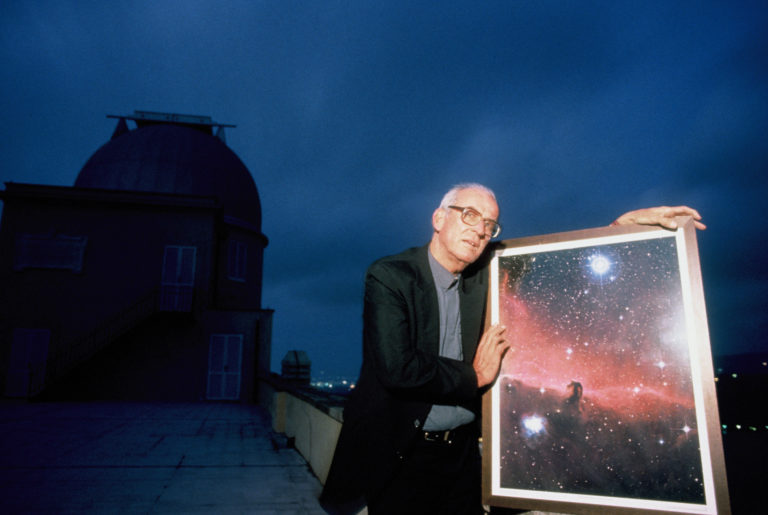

Martin Rees

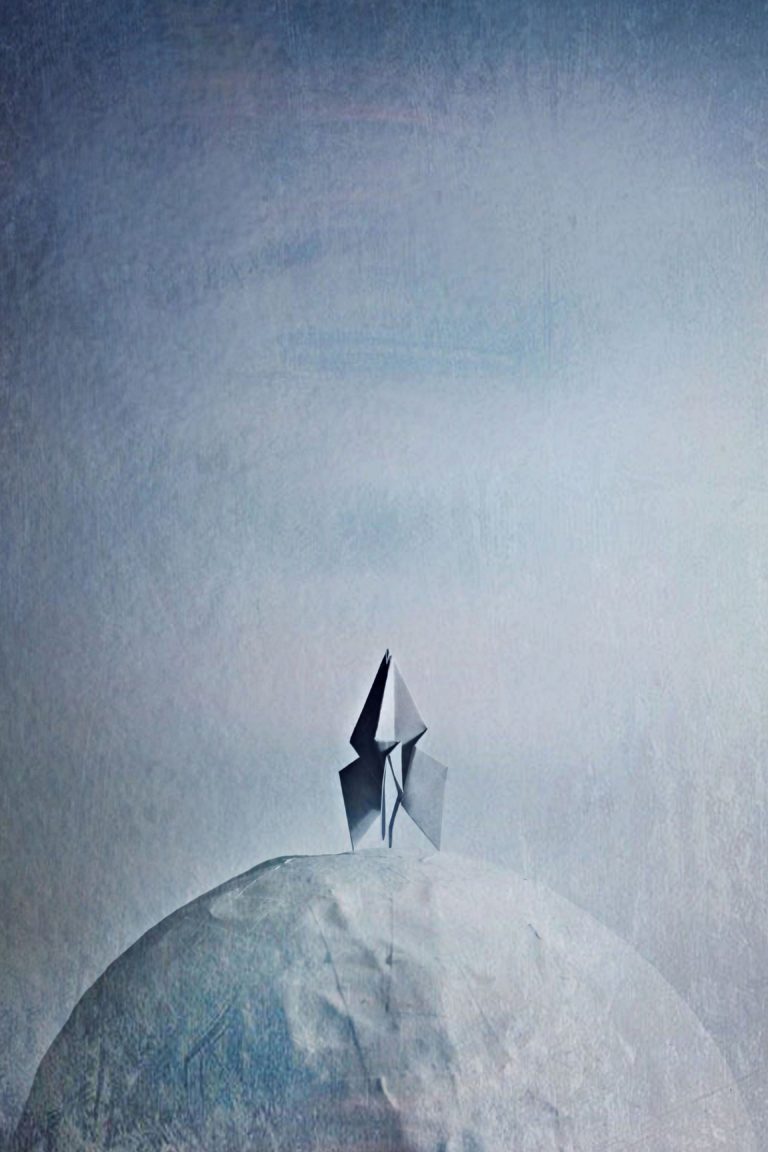

Cosmic Origami and What We Don't Know

Parallel realities and the deep structure of space-time sound like science fiction. These are matters of real scientific inquiry. Lord Martin Rees is an astrophysicist and self-professed atheist who paints a fascinating picture of how we might be changed by what we do not yet know.

Image by Jasenka Arbanas/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Martin Rees is Master of Trinity College and Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics at the University of Cambridge.

Transcript

November 21, 2013

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Some of the biggest philosophical and ethical questions of this century may be raised on scientific frontiers — as we gain a better understanding of the deep structure of space and time and the wilder “microworld.” Astrophysicist Martin Rees paints a fascinating picture of how we might be changed by what we do not yet know.

LORD MARTIN REES: Even empty space has a kind of structure, and we don’t understand that at all. In fact, uh, most of us would guess that empty space does have a structure but on a tiny, tiny scale. There’s fascinating ideas and one of the fascinating ideas is that if you could chop up space on a very tiny scale, you would find that what we think of as just a little point in space is actually a tightly wrapped origami of extra dimensions over and above the three that we are familiar with.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett this is On Being. Stay with us.

Parallel realities and the deep structure of space-time sound like science fiction. But these are matters of real scientific inquiry. Lord Martin Rees is a cosmologist and astrophysicist who spends his life contemplating such things. And I’m strangely comforted by his insistence that we ourselves, human beings, are the most complex cosmic phenomena by far. Though, Martin Rees says, we’re probably not the apex of evolution. He points at philosophical frontiers, and ethical frontiers, that citizens and scientists, religious and nonreligious, must enter together — and with humility all around.

[Music: “Kreutz” by Carl Stone]

LORD REES: If science teaches me anything, it teaches me that even simple things like an atom are fairly hard to understand. And that makes me skeptical of anyone who claims to have the last word or complete understanding of any deep aspect of reality.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being.

Martin Rees holds the honorary title of Astronomer Royal. From 2005 to 2010, he was president of Britain’s Royal Society — the august scientific fellowship to which Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, and Stephen Hawking have all belonged. And he recently drew criticism from some scientists and atheists when he accepted the 2011 Templeton Prize. Full disclosure — this program receives John Templeton Foundation funding for some of our shows on science and religion. The Templeton Prize honors “an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension.” Interestingly though, Martin Rees is atheist. And as I learned when I sat down to talk with him, he has little interest in science-religion battles or science-religion dialogue per se. He’s much happier reflecting on unexpected discoveries in his lifetime — and bringing these into relief as a subject for common life.

MS. TIPPETT: So tell me when and how cosmology captured your imagination. Can you trace that?

LORD REES: Well, it didn’t happen early I, um, decided I wanted to do some kind of science and by a series of lucky accidents actually I ended up doing astronomy and cosmology. They were lucky accidents in two respects. First, I was fortunate to get a very charismatic advisor.

And the second reason I was lucky was that this was, uh, way back in the mid-1960s, and that was the time when the subject was just opening up. The first good evidence that there was a Big Bang was coming online, the first evidence for black holes, etcetera. So it was a very good time to be entering a subject, because when the subject is new the experience of the old guys is at a heavy discount as it were. And, uh, see it’s easy for a young person who is committed to make an impact fairly quickly.

MS. TIPPETT: And you know one of the ways you talk about one of the — a focus of you’re, uh, you’re scientific passion one of the few things that occupies you is this deep structure of space and time, which is wonderfully intriguing language. And — and that’s also what you mean by the deep structure of space and time is something even that amidst those great developments of the 1960s no one had any idea right — of many aspects of this?

LORD REES: Right. Well one of the things we’ve learned is that in the universe there’s obviously stars and galaxies, which are made up of atoms, which as far as we know are just like the atoms we can study in lab. But there is also some stuff out there which is very important because it exerts a strong gravitational force, which is a kind of particle, which we don’t know about and haven’t yet discovered here on Earth.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: So the nature of the so-called dark matter is a big issue for physics and for astronomy at the moment, but there is also another other deeper mystery, which is related to the nature of space itself. There’s evidence, which has come about in the last 10 years or so that even empty space, when you take away all the dark matter and all the atoms, still exerts a kind of force. It exerts a sort of push or tension on everything.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

LORD REES: And this therefore means that even empty space has a kind of structure, and we don’t understand that at all. In fact, uh, most of us would guess that empty space does have a structure but on a tiny, tiny scale, a scale a billion, billion times smaller than an atomic nucleus.

MS. TIPPETT: Huh?

LORD REES: And we would have to understand, uh, space on that tiny scale to understand its structure. There’s fascinating ideas and one of the fascinating ideas is that if you could chop up space on a very tiny scale, you would find that what we think of as just a little point in space is actually a tightly wrapped origami of extra dimensions.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. Right. Right.

LORD REES: We’re used to the idea of three dimensions of space, backwards and forwards, left and right, up and down. But if you look at space on a tiny scale, you would find evidence for extra dimensions.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: The analogy is often given of this is that if you look at a, um, hose pipe from a long way away you think it’s a one-dimensional structure, a line, but if you get close up to it you realize it’s really, uh, got a thickness and is a three-dimensional structure. Likewise, we think that on this very, very tiny scale there may be extra dimensions over and above the three that we are familiar with. And that indicates the mathematical challenge of trying to understand space at the very deepest level.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a mathematical challenge and also imaginative challenge, right, I mean, it almost exceeds the capacities of human imagination to think about.

LORD REES: Um, well of course, the human imagination needs to be channeled by experimental observations.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

LORD REES: And the trouble here is we don’t really have enough observations. But, uh, just to add a footnote to what I just said …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: Um, many people believe that there are these extra dimensions, which we don’t perceive because they’re rolled up very tightly. There’s another idea, which is even more fascinating in my opinion, which is that, um, there may be extra dimensions which are not rolled up, and indeed this leads to the fascinating idea that there may be other universes, other regions of space/time, which are separate from ours, um, because they’re embedded in a common higher dimension.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: To give an analogy of this, I mean, if you imagine a whole lot of bugs crawling around on a big sheet of paper. They may think of that as their sort of two-dimensional universe. They can just go in two directions on it.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: Then if you imagine another sheet of paper parallel to the first one and other bugs on that, then they think they are in a separate two-dimensional space and they’re not aware of the third dimension. So they wouldn’t know that there is the other parallel sheet. And some people think that one dimension up we are in that sort of predicament. They think that there may be, as it were, another universe maybe just a few millimeters away from ours. But if those millimeters are measured in a fourth spatial dimension and we’re imprisoned in our three we wouldn’t know about it.

[Music: “A Mountain of Ice” by Helios]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: “Cosmic Origami and What We Don’t Know with Martin Rees,” with astrophysicist Martin Rees.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve also said that, uh, that in addition to the cosmic scales and the “microworld,” there’s a third frontier of the very complex. And you include, very interestingly, human beings in that — on that frontier of the very complex — the most complex entities we know of.

LORD REES: Well, indeed I think even a small insect is much more complicated than a star because a star is huge ball of gas and it’s crushed by gravity and is so hot that all chemicals are broken down into their atomic constituencies.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: There’s no complex structure, whereas even a small insect has a layer upon layer of structure — protein, cells, and all the rest of it. And so, the smallest living thing is indeed more complicated than a star. And also, to go back to your point, everything about humans is very complicated. In fact, it may seem ironic that I could talk with some confidence about, uh, a galaxy a billion light years away …

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

LORD REES: … and what it’s made of, whereas, I would hope that I could give you evidence so you take what I say seriously. On the other hand, you’re very foolish if you take seriously what anyone tells you about diet or child care, because they change their opinions as you know every year. It’s not that the people working in those fields are less competent it’s that anything to do with, uh, humans and their behavior and their environment is far more complicated than the cosmos or the “micro world.”

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. I want to ask you about something that you said. I want to understand this better: You’ve said that if Newton and Einstein are icons of unification. Darwin is this — is the icon of this complexity that we are discussing. You’ve also said that, uh, that Darwinian pace of evolution and extinction is speeding up. What do you mean by that and how — how do you measure that? I’ve never heard anyone say that.

LORD REES: Well of course, we know that humans have evolved by a Darwinian process of natural selection over a time of nearly 4 billion years, since the Earth was young. But one important thing which we learned from astronomy is that the time lying ahead is at least as long as the time that has elapsed up till now. The Sun is less than halfway through its life. The Earth has billions of years ahead of it, and the universe may go on forever. And I think this is very important to everyone because this makes me very skeptical about any claim that humans are in any sense the culmination of evolution.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: We are, of course, the most complex organism that has evolved, but since the time lying ahead is just as long, then post-human evolution here on Earth and far beyond could be far more complex and wonderful than the biosphere we have here under which we are a part.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

LORD REES: But the other point, which strengthens this claim that we are not the culmination is that any future evolution of humans is not going to be determined by natural selection on the very slow time scale that led to our own emergence from the common ancestor of us and the apes.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, how do we — how do we know that? How …

LORD REES: Well, because, uh, it’s going to be driven by technology and we know …

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

LORD REES: … that, uh …

MS. TIPPETT: So we are speeding it up?

LORD REES: We are speeding it up, and so any, uh, um, changes to humans will come about as a result of applications of genetics or cyborg technology, um, mad machines, symbiosis, and things like that. And this can happen on the time scale of technological advance, which is far, far shorter.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. It’s — it’s interesting to think about that, because, um, you know, one of the things I’ve discussed with other scientists and also people who know Darwin, uh, is that one of the things that’s hard about the theory of evolution for people to grasp is simply to think in terms of that magnitude of time. Right? That the glacial pace defies our ability to accept these ideas, but then we’re all living in this moment where, as you say, the pace of technology is not really faster it’s dizzying.

LORD REES: Yes, absolutely. I mean, it’s nice to imagine, you know, supposing that some aliens have been watching us for billions of years, uh, what would they have seen? They’d have seen very gradual changes, as ice ages came and went and a species evolved and the vegetation changed. But then suddenly, a few hundred years ago, they’d have detected much more rapid changes due to the impact of humans on the environment.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

LORD REES: And then they’d have detected radio waves coming from the Earth — the integrated effect of TVs and radars and all the rest of it. They’d have detected, uh, an anomalous sudden rise in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere because of human activities. And they would have detected amazingly, for the very first time in 4 billion years, little projectiles leaving the Earth and going into orbit around it …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: … the first spacecraft. And so, uh, they would have observed all these things happening in essentially a few centuries, which is just a …

MS. TIPPETT: Kind of a blip.

LORD REES: … tiny blip, because the Earth has existed for 45 million centuries.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

LORD REES: So things are really accelerating. And that makes it even harder to predict what could happen given the huge expanse that lies ahead.

MS. TIPPETT: So — so what we’re, you know, all of this is — is evoking, um, for me is also something that you, uh, I think are very articulate about, which is they way without overtly being philosophical or theological or ethical, science, especially modern science, especially something like cosmology, raises insights and questions that are relevant philosophically, ethically, theologically.

LORD REES: Well, very much so. I mean, I think we should distinguish that philosophy and theology on the one hand, from the ethics, because obviously all the advances in science lead to a range of applications, some of which are benign others less so of course.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: We entered this era with the nuclear age in particular, and we’re going to have more and more difficult choices as to how we apply science, so that we can benefit from it but avoid the down sides.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: But separate from the applications of science, there is also the general way in which our perception of our place in nature …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: … is changed by science and obviously — obviously there have been very important developments in the last decade leading to the awareness that most of the stars we can see in the sky aren’t just twinkly points of light. Most of them are orbited by a retinue of planets, just as the Sun is orbited by the Earth and the other planets we are familiar with: Mars, Venus, Jupiter, etcetera. And this of course makes the night sky much more interesting, but also opens up the question of whether on any of these other planets life got started …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: … as it did here on Earth. And whether having got started it evolved in any places to complex life of a kind that we could recognize as intelligent. I mean, this is, of course, a staple of science fiction, but these are issues which are now an important part of science.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. So not only thinking — giving us perspective on our place in the cosmos, but raising anew the question of whether we are alone in the universe?

LORD REES: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: Yes.

[Music: “Kreutz” by Carl Stone]

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve also made some pretty dramatic statements that you think mankind has a 50/50 chance of surviving the century. Someone said this is the scientific version of apocalyptic reasoning. Tell me — tell me what you mean by that.

LORD REES: Well, I didn’t quite say anything as scary as that.

MS. TIPPETT: You didn’t. All right. That’s what was reported.

LORD REES: What — what I said, uh, what I said a 50 percent chance of a severe setback to civilization.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. All right.

LORD REES: OK. I don’t think we’ll wipe ourselves out. I mean, that’s very unlikely, but I did say in a book a few years ago, which was called Our Final Century in Britain and Our Final Hour in America. Um, that says something about …

MS. TIPPETT: We like things to happen more — yes it does — our sense of time in history.

LORD REES: … the difference in the time span Britains and Americans think on, perhaps.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. Yep.

LORD REES: But, uh, what I — what I did say was that there were severe threats, um, and I did think it was only a 50/50 chance that we would get to the century having avoided them all. And of course one threat which we’ve been under for the last 50 years is of a nuclear catastrophe.

But another concern I have is that I think that the world is becoming less governable because individuals are far more empowered than they were in the past by technology. The kind of people who now design computer viruses may one day be able to design real viruses and in our interconnected world …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: … even computer viruses can be more and more dangerous. And so, uh, I’m worried that a few weirdoes or …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: … disaffected extremists can do far more damage in the future then they’ve been able to up ’til now because they are more empowered.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. So you know, I — I thought a lot about a statement that Einstein made in the early 20th century as he, you know, to his great dismay watched chemists and physicists create weapons of mass destruction, and he said that science in his generation — he likened it to a — a razor blade in the hands of a three year old. And you know, we — we can look back on this moment of splitting the atom and we can see that that had incredible destructive potential and it still does, also incredible healing and life-giving potential.

It occurs to me that — and I wonder what you think about this moment in time where we’re living through some of these, uh, choices and possibilities, as you say, like with climate, um, there’s a great kind of awareness of the double-edged sword of these things as they’re unfolding in real time. I think what you’re also saying though is that this doesn’t just need to be a moment of scientists, uh, taking seriously the implications of their work, but that — that citizens, that everyone has a stake in this and also has some power over technology that previously was not so dispersed.

LORD REES: Yes. Absolutely. Of course Einstein’s staple is even more relevant today.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: And, uh, I quote another one, it was H.G. Wells said that this century would be a race between education and catastrophe. And we’ve got to make sure that education wins. And, uh, indeed the stakes are higher than ever before. I mean, I think we shouldn’t be too gloomy, because despite the risks and the threats that have hung over us for the last 50 years, let’s not forget the benefits of the communication revolution and, of course, of improved health for most of the world’s people.

But of course, even now we can see a big gap between what actually happens and what could happen, because we know the world is about a billion living on less than a dollar or dollar and a half a day and without access to clean water etcetera, could easily have their predicament alleviated if the will were there.

MS. TIPPETT: You know in your Reith Lectures, you give some — in addition to these issues that you just named, these huge issues of poverty, I mean, you — you name some very practical questions that scientific advances are raising that — and, you know, you are advocating for a smarter, more thoughtful public dialogue about this. So, you know, how will lengthening life spans effect society? Who should access the readout of our personal genetic code? Should the law allow designer babies?

LORD REES: That’s right these are all questions which the public does need to decide, and I think it’s important that scientists, as science citizens, should raise them on the agenda because, of course, the other problem is that most of these issues, which are important for the world and for society, are long term. And in politics, the urgent always trumps the important.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. Yes.

LORD REES: Especially when the electoral cycle is short. And so I think one thing that scientists can do is to raise their profile and make sure that the public doesn’t forget these longer-term issues. But I think we have some good role models among scientists. I think among the most impressive individuals I’ve met in my life have been some of the great physicists who work …

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm, who — who do you think of?

LORD REES: Well, I mean, I — I mentioned two who I was privileged to know. One was Hans Bethe, who was a great physicist, who died a few years ago at the age of 98. And he was someone who did great work in nuclear physics. Back in the 1930s, he was head of theoretical division at Los Alamos during the World War II, the development of the first atomic bomb. But, uh, he went back to academia remained a productive scientist until he was over 90 years old. But at the same time he was engaged in politics. He felt it was his obligation to help to control the power he had help unleash, namely the …

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

LORD REES: … power of the nucleus. And he devoted his energies throughout his long life to this aim. As did also Jozef Rotblat, another scientist whom I was privileged to know, based in England. They I think set a wonderful example of citizen scientists. Of course, they didn’t have immense success. I mean, I think they’ve — they are having success because it’s now accepted that we should aim to cut down the number of nuclear weapons if possible to zero. In fact …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: … even President Obama, in his speech in Prague last year, said that.

MS. TIPPETT: Come full circle, mm-hmm.

LORD REES: So that is now a mainstream idea. But I think scientists should exert whatever influence they can, even though they won’t always succeed. And even though, of course, other opinions are also clearly valuable. To give an analogy, if you are parents you can’t necessarily control what happens to your teenage or adult children.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: Um, but you are a poor parent if you don’t care what happens to them.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: Likewise, you’re therefore a poor scientist if you don’t care about how your creations are applied.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

LORD REES: And so that’s why scientists have, I think, a special obligation to express concern and to warn or encourage the wider public about the applications of the ideas, which they understand best as anyone.

[Music: “Niedrige Decken” by Burnt Friedman & Jaki Liebezeit]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with astrophysicist Martin Rees through our website, onbeing.org. There you will also find Martin Rees’s Reith Lectures. They give a sweeping view of the past half century of scientific advance. They’re also compelling reading and listening for non-scientists. Again, that’s onbeing.org.

And on the Being Blog right now, as events in the Middle East continue to unfold, we’re featuring a video profile of two communities — an Arab village and a Jewish kibbutz. For years, they’ve shared a well, harvested crops together, and attended rituals of each others’ lives. Also, Melody Moezzi writes that the spiritual leader the Iranian people turn to is not a hard-line Islamist, but a Sufi mystic poet: Rumi. Find all this at OnBeing.org.

Coming up, Martin Rees on atheists and religious as allies in applying science to life.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Buildings and People” by Marconi Union]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: I’m in a big conversation with Lord Martin Rees, cosmologist, astrophysicist, and recent past president of Great Britain’s scientific Royal Society. He’s describing unfolding discoveries — and questions — on modern scientific frontiers: from the deep structure of space and time, to the wilder “microworld,” and the most complex thing he knows of all, human life.

MS. TIPPETT: You are atheist but very — have been very vocal about not seeing science and religion as adversarial aspects of human life. I also sense that you are kind of agnostic on the idea of whether that means there should be all kinds of dialogue. But one thing that occurs to me in this discussion we’re having now about a philosophical and moral, uh, quandaries that are presented by science is that to me it really heightens the challenge also for theologians, um, religious leaders who are keepers of this — these ancient traditions, which have moral reasoning at their heart to also apply those and bring — bring the depths of those into our public life in a different way.

LORD REES: Well, indeed I think obviously all religious leaders need to be mindful of, uh, what we have learned about the world and the environment and about life through the advances of science. And I should say that I am not a person who adheres to any religious dogma. And I think the reason I take that view is that if science teaches me anything, it teaches me that even simple things like an atom are fairly hard to understand. And that makes me skeptical of anyone who claims to have the last word or complete understanding of any deep aspect of reality.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: I think the most we can hope for is some incomplete and metaphorical understanding and to share the mystery and wonder whether we are believers or not.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: And so I find myself very out of tune with old dogmatic religions, which I suppose includes all the three Abrahamic religions. Although, of course, I can see a closer affinity with Confucianism and systems of thought like that.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, although, I did once speak with an Anglican theologian who is also a geneticist here in the United States, who — he’s an Anglican priest, and he said that he likens the creeds of the Church to operational hypothesis.

LORD REES: Some people do decide to behave as if some — something is true.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: And, uh, and they of course are entitled to do that.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. We have a lot of listeners who are atheists and agnostic, and you know, they have ethical lives and they have spiritual lives. I think it depends on how you define that, but they are asking these questions of meaning. It has felt in recent years that it was hard to, uh, that there wasn’t much middle ground. There’s middle ground in peoples lives but in our public life, right, there’s the new atheist revival or there’s religion. I think you — you are also arguing for some kind of different space for seeing the relationship between these things, or at least defusing the idea that the relationship is adversarial. I wonder if you would just speak to that.

LORD REES: Well, I’d say two things. I mean, first there are some very distinguished scientists who do have a traditional religious beliefs. I — I know a number of them. I find it hard to understand how they can adhere to these beliefs in the way they do, but plainly they do. They have these beliefs and we must respect them and we should not in any sense belief that they are less good scientists for that reason. So we — we should accept that there are many scientists who do have religious beliefs of all kind, as well as many who don’t. But the other point I’d make is that even many of us who don’t have religious beliefs favor the idea of, as it were, a peaceful coexistence.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

LORD REES: Um, in fact, Stephen Jay Gould had a rather pretentious name for this called, Nonoverlapping Magisteria.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

LORD REES: And this is really the idea that you can have a religious discourse and you can have a scientific discourse. And it’s rather interesting that there was a survey done of members of the Royal Society, which is a British Academy of Science.

MS. TIPPETT: August institution, which you led.

LORD REES: Of which I was recently president.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: And, uh, it was a rather incomplete survey and you might have caught a respondent, so I don’t know how reliable it is, but of those who responded only a small minority were believers in a personal God, in a traditional way. But more than half of them believed in peaceful coexistence. So in other words, the sort of strident views that one should be hostile to religion — a strident view which is espoused by a few high-profile scientists is one which they have of course deeply share, but they should not regard that as being typical of nonbelieving scientists.

Many nonbelieving scientists, like myself, do not wish to attack and deride religion in the same way. And indeed one of my disagreements with these people is that I regard fundamentalism, both Christian and Islamic, and New Age as being a real danger to the world. And I therefore, think we need all the allies we can muster against it. And I would see the mainstream religions, religions that have no problem whatever with science, as being our allies.

[Music: “Niedrige Decken” by Burnt Friedman & Jaki Liebezeit]

MS. TIPPETT: This is not so much any kind of theological or philosophical principle, but there’s a way in which — there’s a lot of wisdom in the history of scientific discovery, which is a template for life, even as you say, this complex system of life. So for example, what I’m thinking of there is that progress in science is very — is always implicated with failure or with the unsettling, the overt unsettling of what was thought to be real and true.

LORD REES: Absolutely, I think science doesn’t advance in a very systematic way. It advances with sometimes two steps forward and one step back.

MS. TIPPETT: And you know what I’m saying, that’s also how life is, but we kind of …

LORD REES: Oh absolutely, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: We — we pretend in many of our other academic disciplines that it’s all about — that progress is this arrow forward and science is very honest.

LORD REES: Yes, well, uh, I would agree with you that there’s a great similarity between the way scientists think and others do. I think there’s a lot of pretentious talk about the scientific method as though it’s something special. But I don’t think there is anything different between the way a scientist thinks and works and the way, say, a detective works …

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

LORD REES: … trying to solve a forensic case, you know. You — you’re trying to access the evidence and get things to fit in to a pattern and decide how to weigh seemingly contradictory bits of evidence etcetera.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. Right and that you may make — may go in wrong directions but in fact …

LORD REES: Oh absolutely and — and …

MS. TIPPETT: … but in fact — that those may reveal ways towards something that you couldn’t see before.

LORD REES: Absolutely, and — and of course, there are — there are sort of revolutions, which overthrow a whole body of ideas. I think actually people slightly overstate how often these revolutions happen.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: When we actually have to go back to the beginning. There are some, I mean, for instance, realizing that the Earth isn’t the center of the universe, but the Sun is — that was a big, big change. And I would say that the quantum theory was another big change. But mostly what happens in science is that new ideas are refinements and extensions of the old ones. For instance, I mean, Einstein didn’t prove Newton was wrong. Einstein provided a theory which had a wider range of applicability of Sir Newton and gave us a deeper insight in to what was going on to produce the gravitational force.

But Newton’s theory is still good enough to program rockets to fly to the planets. It’s not been proved wrong, and that’s more typical actually. Science advances and old ideas get absorbed into a more extensive field of broader applicability. And that incidentally is a good hope for science. Where people sometimes worry about science getting so complicated that, uh, that it’ll grind to a halt, because there is too much to learn. It’s true that the amount of data is growing very fast and we need computer methods to analyze it all. But the aim of science is to unify disparate ideas, so we don’t need to remember them all. I mean we don’t need to record the fall of every apple, because Newton told us they all fall the same way.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

LORD REES: And likewise, when you understand nature in increasingly general ways, then the number of separate things you have to remember goes down not up. So, that’s why I don’t think one should expect that science will grind to halt for that reason. It may grind to a halt for other reasons, like some problems being just too difficult for us. But it won’t grind to a halt because of information overload in my opinion.

[Music: “Jardin” by Gustavo Santaolalla]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today, “Cosmic Origami and What We Don’t Know with Martin Rees,” with astrophysicist Martin Rees.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you think so — you’ve said you don’t think science will grind to a halt because of complexity but — but I do have the impression from some conversations with scientists that it — it seems, and to many people’s surprise, here at the dawn of the 21st century where a couple decades ago it looked like a lot of — some of these big issues would be tied up. I mean, does it seem like there are more unknowns or bigger ones, um, at this moment — or maybe than you expected when you started your — your, uh, scientific career several decades ago.

LORD REES: Well, I think what happened in science is that, as it advances, the frontiers, as it were, get more extensive and new questions come into focus just beyond the frontiers. But I think, at the same time, some areas advance fast and others advance slow, and we can’t predict the rate of advance. I mean, this is true in technology for instance. I mean, when I was young, I thought that we’d have bases on the moon now and we’d all be flying in supersonic planes.

MS. TIPPETT: Did you?

LORD REES: And many people did. And of course, we’re not doing that because there was no economic or social motive to deploy the resources that way. On the other hand, I think, something like, um, an — an iPad, would have been thought magic even just 10 years ago.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

LORD REES: And so, and so the technology that has led to mobile phones and GPS and iPads and all that has evolved and disseminated worldwide far faster. So in technology, it’s easier to predict the trend than to predict the rates. But as far as science is concerned — I think, in my field we have made rapid progress in a number of areas. But the one in which the progress has been fastest is actually in discovering planets around other stars. This is the field that didn’t exist at all until 15 years ago and is now one of the most lively and rapidly developing fields of science.

So that’s developing faster, whereas some of the problems posed by subnuclear physics have been rather stagnating and haven’t made as much progress as we hoped.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you very often in your speeches and your writing have used this analogy of, um, science is frontiers of — as like the moments where ancient cartographers would come to the end of what they knew to be there.

LORD REES: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And they would inscribe, there be dragons.

LORD REES: Yes, yes. Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: It — it also occurs to me just as we’re speaking that right now it’s sort of — on television, for example there’s a lot of programming and a lot of it actually being produced in Britain as much as the U.S., um, is it like this Game of Thrones this new — there’s — there’s kind of semi-science fiction, which — which also evokes these places beyond which — where you know there might be dragons. And I wonder if — I don’t know, I’m really thinking out loud — if that is in a sense kind of modern people, um, somehow by osmosis as much as education perhaps picking up these renewed frontiers and mystery at the edges of human knowledge.

LORD REES: Well, I think science fiction and these computer games do in a sense nourish and extend the imagination and, you know, I tell my students that they’d probably do better to read good science fiction then second-rate science, because science fiction is more fun and no more likely to be wrong then the second-rate science. And — but I think you’re quite right in saying that many people are familiar through imaginative literature and computer games with ideas of worlds beyond are own, etcetera, etcetera. And I think this is, um, a good thing, because anything which broadens our horizons in space and time away from the parochial concerns which dominate the political agenda, I think, is a very good thing.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. And, I mean, even the notion of virtual reality perhaps making us be more receptive to some of these pretty far-out things that you describe about perhaps that the, uh, these origami — these rolled up worlds, parallel universes that has always felt like the stuff of science fiction but is looking more like there might be something to it.

LORD REES: Well, that’s right and I think, um, also the progress of science in the areas I work in is crucially dependant on, in effect, computer models in a virtual world or a virtual universe …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: … because we can’t do experiments. We can only do make observations, but we can do experiments in a virtual world by computer. For instance, um, we understand quite a lot about galaxies because we can observe them. And we can also, in our computers, work out what happens if they are crashed together, for instance …

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

LORD REES: … and crashing stars together, making stars explode and, uh, we can do all this in our computer speeded up a billion, billion times compared to the real rate at which these things happen. So we can actually study these quite quickly. And then we look in the sky and see if the output of our calculation resembles what we actually see. And I think if we look ahead, then we are going to see huge further advances in computer technology and robotics and miniaturization. And this is going to enhance our intuition in many ways. It’s an aid to thought.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: And so I think one of the reasons I’m optimistic about us continuing to develop a deeper understanding of the natural world is that we would be aided not just by obviously more precise and elaborate instruments, but by these interfaces between our own brain and some silicone brain as it were, which is going to help us. And these interactions become more close and more sophisticated. And I think that’s going to be a fairly rapid change if we just think of how much there’s been developed just in the last 10 years.

[Music: “Plastic People” by Four Tet]

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I sense — and I’d like to tease you out on this because I — it’s not something that you — or at least that I’ve found you’ve written about overtly, but you note that among cosmologists, people who deal with the universe on the scale that you do, astrophysicists, um, that the poles and I — you know, I think again these polls are what get us into trouble. But the polls are people who say, well you study this universe and it’s so unlikely that everything game together to create this hospitable biosphere that there must be some purpose behind it, whether they call that God or not. And then there’s another poll that says, uh, it’s a random accident. It’s an incredible, exquisite random accident. I sense that you want to assume a place that’s somewhere between those two things, but I’m not sure, uh …

LORD REES: Well, I — I regard this as a question which is a scientific question …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: … not a metaphysical question, albeit a very speculative scientific question. I think we do want to know how much is there, in physical reality as it were, beyond the part of the universe we can see with our telescopes. Does it go much further? Are there completely disconnected regions of space and time? And if so, are they all governed by the same physical laws or could it be that there are different physical laws, so that what we’ve called the universal laws are really just bylaws? And that I think is one of the important questions. And incidentally, I think when we have this unified theory of the very large and the very small and the nature of space, it will help to settle that question. Because one of the key questions is whether there is, as it were, only one form of space or many different forms of space.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

LORD REES: That’s an important question, which string theorists worry about. And that is very strongly linked to this question of whether the things like the strength of gravity and the mass of the electron are universal or whether they could in principle have different values elsewhere.

MS. TIPPETT: And do you rule out, um, the possibility of — or if — if this unfolded in this way would it, for you, rule out the possibility of purpose or of a — you know, a creative intelligence or what is it Einstein mined behind the universe.

LORD REES: Well, I — mean I think to be — I just don’t understand what could be meant by purpose. I think if there was a purpose, I wouldn’t expect human brains to be able to understand it. I think it is clear that humans are just a stage in the emergence of amazing complexity in the universe. And I just think it’s far too anthropomorphic to actually use the word purpose.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Um …

LORD REES: I mean, I — I think it seems to me that we, uh, are part of this world, many aspects of which are mysterious. Perhaps the most mysterious is that we exist and are conscious and able to wonder about how we came to be here. But, uh, I regard the rest as a mystery, and perhaps it will have to await the evolution of some species more advanced than humans to make more sense of it. So it is just a mystery to me.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. You just mentioned consciousness, which is — which is part of what makes us think about something like God.

LORD REES: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Or want to understand the nature of stars. Just curious, you know, that is — I see that as one of these huge frontiers, um, of our time. How do you as an astrophysicist, a cosmologist, observe that development and think about its possibilities? Does it inform what you do and how you make sense of it all?

LORD REES: Well, again, I think the brain is the most complicated thing we know about in the universe. And we are just beginning to understand it. And there are lots of ideas, of course, but that is in my view the sort of Everest problem, as it were — the highest summit in studying the complexions of our world. And how far we will get in solving that I don’t know, but there are many mysteries still obviously. But again, the point I want to emphasize, is that we should not be surprised that there are many mysteries, because we are just beginning and the world is very complicated and our brains may not be up to solving all of them.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. I love this story you told about — and I think this is how some thing can be gained in popular translation that then can be valuable to scientists. You told a story about Robert Wilson at Bell Labs detecting weak microwaves that are a relic of the Big Bang. But that he didn’t appreciate the full import of what he’d done until he read a journalist’s description of what he had detected as the “afterglow of creation.”

LORD REES: Yes, yes. Well, I mean, um, that raises two points. One is that, of course, scientists obviously are aware of the big problems, but they don’t tackle the big problems head on. They work on a problem which they think they can solve. Peter Medawar, one of my scientific heroes, said that no scientist gets credit for failing to solve problems beyond their competence; they earn at best the kind of contempt reserved for utopian politicians. So scientists tend to work on a sort of bite-sized small problem.

But the occupational risk then is that they forget that their small problem is worthwhile only because it’s helping to illuminate the big picture. And I thought that anecdote about Robert Wilson was rather nice because he made one of the greatest discoveries of the century But the way he did it was by tinkering with the antennae of a radio dish and making sure he got rid of all the background, etcetera. He was doing detailed technical things, and he was so focused obviously on doing that because that was his expertise that it didn’t really sink in what a great discovery he’d made.

And — and so I think that’s why it is important for scientist to engage with the public. Because if you talk to a general audience, then the questions they ask are, of course, the big questions. They don’t care about these tiny technical details.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm. Right.

LORD REES: And if we talk to the public, they remind us that the big questions are important and also they remind us that most of those big questions haven’t yet been solved.

[Music: “We Insist” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: Martin Rees is Fellow of Trinity College and Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics at the University of Cambridge. He’s the author of several books, including Our Cosmic Habitat.

To listen again or share this show with Martin Rees go to our website onbeing.org. On Facebook, we’re at facebook.com/onbeing. On Twitter, you can follow our show @beingtweets. And follow everything we do through our weekly email newsletter. Subscribe by clicking the newsletter link on any page at onbeing.org.

[Music: “Candor” by Balmorhea]

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mikel Elcessor and Megan Bender.

[Announcements]

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT:Speaking with Martin Rees reminded me of a conversation I had early on in this show with a geneticist who’s also an anglican priest, Lindon Eaves. It was an experience of the ongoing conversation he says he conducts all the time within himself.

MR. EAVES: I would say there are plenty of times when I just need to keep religion at bay in order to do my job properly. I mean, to be a thorough-going scientist I am compelled in the short term to see really good reasons for not believing the current model for reality because that’s how science perceives. That’s a conversation between the past and the future with a real belief that everything we’ve believed in the past may turn out to be wrong.

MS TIPPETT: [laugh] Which is really the opposite of a biblical worldview.

MR. EAVES: Certainly, if you take the sort of the conventional kind of religious approach, yes, it feels very different. But then I say, if you really look at human experience, the truth is that we’re all living a life of experiment. In every aspect of our lives.

I mean, you can either think of, lets say the creeds of the great traditions as it were, as telling you what you ought to think. Or you can say they are in some some sense comparable to the theories of science. They are the best distillations of where we’ve been. But we don’t approach reality treating those models as if they are the last word. We treat them as operational hypotheses.

MS.TIPPETT: Geneticist and Anglican priest Lindon Eaves. One of my favorite interviews ever. Hear more at onbeing.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections