Paul Muldoon

A Conversation with Verse

The Irish poet and New Yorker poetry editor Paul Muldoon has won the Pulitzer Prize, written for other media from radio to song, and plays in a rock band. He visited us for a magical day at the On Being studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis, including a dinner salon and reading from his work.

Guest

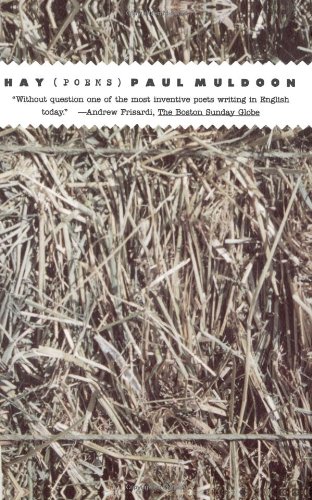

Paul Muldoon is the Howard G.B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities at Princeton University and is the poetry editor of the The New Yorker. He is the author of 12 major collections of poetry, including Horse Latitudes, Hay, and One Thousand Things Worth Knowing.

Transcript

December 22, 2015

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MR. PAUL MULDOON: “I’m interested in revelation, in what will be revealed through the poem, through me — not what I have to reveal, but what it has to reveal.”

MS. KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Today, a conversation with verse, with the Irish poet and New Yorker poetry editor Paul Muldoon. He’s won the Pulitzer Prize, written for other media from radio to song, and plays in a rock band, Rogue Oliphant. He visited us for a magical day at the On Being studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis, including a dinner salon and reading from his work — like this excerpt from his poem called “Pelt.”

MR. MULDOON:They piled

it on all day

till I gave way

to a contentment

I’d not felt in years,

not since that winter

I’d worn the world

against my skin,

worn it fur side in.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: Paul Muldoon holds the Howard G.B. Clark chair in the Humanities at Princeton University. He’s been with the The New Yorker since 2007. And he is the author of 12 major collections of poetry, including Horse Latitudes, Hay and his latest collection, One Thousand Things Worth Knowing.

MS. TIPPETT: So, you were born in County Armagh, in Northern Ireland, in a Catholic family, in the Moy. The Moy was the name of the village?

MR. MULDOON: The Moy is the name of the village. It’s the village nearby. It’s actually on the border of counties Armagh and Tyrone. So it’s about halfway across Northern Ireland.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, I see, OK. Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: And we were actually in County Armagh, but the Moy itself is in County Tyrone substantially.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. MULDOON: And then there’s a little village across from it, a hamlet really, called Charlemont. So a small place.

MS. TIPPETT: And to be born in that part of the world also was to be born in a place that loved poetry, and kind of lived and breathed story. And I wonder if you think in terms of the spiritual background of your life, expansively defined, would you think about poetry and story as a piece of that, as well?

MR. MULDOON: Well, I would say so, yes. I mean, I wouldn’t have been conscious of that as a child.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. MULDOON: But of course, we were brought up in a culture where, for example, of an evening, a knock might come to the door, and a neighbor would be there, and he would be hoping to come in, and he was welcomed in, and he’d have a cup of tea, at least. And then he — predominately he, but a few women came around, too — would perhaps sing a song, or recite a ballad or a poem. So that was — certainly we were conscious of the larger literary tradition, I mean the tradition in its widest sense, including the oral tradition. So that certainly was part of the back of our mind, too, or perhaps even the front of our mind. But way up front, I think, was the religious aspect. If one had said “spirituality,” that’s what we would’ve been talking about. It was organized religion.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: And Catholicism in particular.

MS. TIPPETT: You noted in another interview that the Celts had a god of eloquence, which I loved, Ogmios. I’m very interested in this question of what poetry gives voice to in us, what it works in human beings. And I’ve discussed this with poets along the way, and I — and musicians. How would you start to talk about what poetry as a form of expression, and also its forms of language, distinctively draws out?

MR. MULDOON: Well, it is a form of expression, of course. It is an expression of something within as well something without, and perhaps, indeed, the point at which the two combine. It’s very difficult to find a decent metaphor for this. One of the defining characteristics of a metaphor, of course, is that it breaks down fairly soon. You know, only up to a point …

MS. TIPPETT: You mean any metaphor?

MR. MULDOON: That’s right, any metaphor. Only up to a point is my love like a red, red rose.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: Only up to a point. So to find a decent way of thinking about it, you know, the expression I — let’s think of what I would say to my students. I mean, the expression of — it’s not as if one is setting out to express oneself. And I say that because, ideally, one has no sense of what is going to come out.

MS. TIPPETT: As a poet, you mean?

MR. MULDOON: As a poet. It’s not as if one has a point of view, I think, ideally. Which is not to say, of course, that there are poems that don’t present points of view, not to say that one has an idea, which is of course not to say that poems don’t express ideas. But that’s not where we begin. We begin again from ignorance, from, perhaps, the germ of something, from a hunch, from a notion that if we take a couple of elements in the world and set them down, something might — something interesting might happen. And gradually, as the poem, in this case, comes into being, what it’s trying to do in the world gradually becomes clear. And it’s only, in fact, as one comes out the other end of it, I think, ideally, that one realizes what it is.

Now, of course, there are other theories of art. I mean, Bertolt Brecht, for example, would say, “Well, actually we have to begin with the idea we’re going to make a political point.” And I absolutely understand that. It’s not the kind of art-making I’m interested in. I’m interested in revelation, in what will be revealed through the poem, through me — not what I have to reveal, but what it has to reveal, if that makes any sense. So I have no revelations at all. I know nothing. I’m not to be trusted on anything. [laughs] But the poem may know something, and may be trusted, actually, on what it has to express in the world, in my practice. Others may think about it differently.

MS. TIPPETT: And as much as you are, it sounds like, perhaps surprised by — there’s a process of discovery for you of what the poem is?

MR. MULDOON: Totally.

MS. TIPPETT: Right?

MR. MULDOON: There’s got to be a process of discovery.

MS. TIPPETT: And then, are you sometimes surprised by that work the poem does in the world, which you also could not have intended? Or how it lands in other people?

MR. MULDOON: Well, yes. I mean, part of the job, of course, is to try to figure out what its impact will be.

MS. TIPPETT: As you’re writing?

MR. MULDOON: As one’s writing.

MS. TIPPETT: All right.

MR. MULDOON: Because if you think about it — again, it’s hard to find a decent analogy for this — but let’s just take it that there are two people involved in the writing of the poem. There’s the writer, who is appealing to her unconscious, to her profound sense of unknowing. And then there’s the reader, who, as the poem comes into being, as I say, as one word puts itself after another, is trying to figure out what the impact of those words in that order might be from a position of knowing. Right? And it’s the negotiation between these two, the unknowing and the knowing, that, crudely put, would represent the positions of the writer and the reader. So if the first reader of the poem is the writer herself, in a strange way the poem is, indeed, only finished, only completely — becomes completely what it might be when that other person comes to it.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, one thing you said — I mean, you, as I say, you’ve done many different kinds of writing in your life.

MR. MULDOON: I have tried.

MS. TIPPETT: Right? And you’ve written for radio, for example, and you’ve written for television, and you’ve written for music. One thing you’ve said about poetry that is distinct from other kinds of writing that intrigues me is that poetry doesn’t build to the big idea like many other kinds of writing, but it starts there, that the poem starts where many kinds of writing would be winding up.

MR. MULDOON: I did say something like that. Of course, one has — I have to think of all the things one has said, including all the daft things one has said, I’m sure. That — I think I recognize what you’re alluding to.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that may have been — there’s a lovely interview in The Paris Review. I think it may have been that interview. And I can just — yeah, I can just ask you, like, how would you talk about how writing a poem is distinct from all those other kinds of writing?

MR. MULDOON: Well, actually, I think it’s often most useful not to think of it as being all that distinct. I think one of the problems with the general perception of poetry is that we think it’s special. And if anything, I think we’d be better served if we thought it was much more like prose fiction. Much more like theater criticism or film criticism than occupying this kind of special realm, Poetryland, you know?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: Poetryville, where all bets are off, anything can happen. And again, I used to say to my students, and still do, if they listen to me — which is unlikely, of course — that I expect the poem to be at least as interesting as the film review in the next column. I expect it to — or at least, in general, there’s no particular reason why it wouldn’t have a beginning, middle, and an end, generally in that order, though of course there are times when that’s not what it needs. And that it make sense, unless for some reason it doesn’t quite.

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] Right.

MR. MULDOON: You know? And that as much thought has gone into it as has gone into a film review or the leader in the local newspaper.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: The op-ed piece. And that it actually — and one comes out the other end of it thinking, “Huh, that was interesting, I’m glad I was in there. I actually learned something in there.” Not necessarily about whether or not the economy is healthy, but perhaps something about the — just a new way of looking at something that one hasn’t quite seen before. A way of looking at a wheelbarrow, a way of looking at a plum in an icebox, some modest little shift in the world, but a shift, a revelation. And, basically, if there isn’t some kind of revelation, it hasn’t been worth one’s while to be in there.

[music: “Plucky” by Atusi Assiv]

MR. MULDOON: At least they weren’t speaking French

when my father sat with his brothers and sisters, two of each, on a ramshackle bench

at the end of a lane marked by two white stones

and made mouth music as they waited, chilled to the bone

Fol-de-rol, fol-de-rol, fol-de-rol-di-oh

for the bus meant to bring their parents back from town.

It came and went. Nothing. One sister was weighed down

By the youngest child. A grocery bag from a town more distant still, in troth.

What started as a cough

Fol-de-rol, fol-de-rol, fol-de-rol-di-oh

would briefly push him forward to some minor renown

then shove him back, oddly summery, down

along the trench

to that far-flung realm where, at least, they weren’t speaking French.

[music: “Plucky” by Atusi Assiv]

MS. TIPPETT: That’s Paul Muldoon reading an excerpt from his poem “At Least They Weren’t Speaking French” at the On Being studios on Loring Park. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

MS. TIPPETT: I think also what you’re alluding to, in a general way, also, is we’re not sure what the place of poetry is in a culture like this. I mean, it’s not the culture you grew up in, where it was lived and breathed and not, as you say, not the domain of Poetryworld, but of ordinary people in ordinary life. You tell a story somewhere about being with your son — your children, that children are natural poets, that somehow that this is with us. You told a story about your son driving along on the highway and saying, “Those lights are like tadpoles.” And we’ve all had that experience.

MR. MULDOON: I think I’ve given one interview too many, I really do. [laughs]

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I may stop …

MR. MULDOON: I vaguely remember that.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, this is one way — but all right, I’ll stop quoting you at yourself.

MR. MULDOON: No, no, no, not at all. I think it is …

MS. TIPPETT: But this idea that, somehow — how does it get lost? What’s your analysis of that?

MR. MULDOON: I’m afraid that, too often, it gets educated out of us.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: I mean, that is something we’ve heard once or twice, maybe more than once or twice. But I really believe this, that the natural capacity that an eight-year-old or a nine-year-old has for coming up with, unselfconsciously, coming up with novel ways of seeing the world, I mean, ways that actually inform us about how the world is. They’re fanciful in some sense, but they’re actually instructive, I think. And one of the reasons why the child — we’ve heard this from William Wordsworth — “The child is father to the man.” And I think, in some sense, she is. Because she is capable of that unprogrammed, unthinking way of seeing the world. No preconceptions, no misconceptions. And there comes a point, actually, where I think we begin to educate that out of them. At some point, we’ll say, “Oh, that’s lovely, that’s very nice.” But at some point, we probably said, “Well, you know, actually, you know, your tadpole analogy doesn’t really hold up. Get serious, get real, grow up.” And that capacity to be innocent and open, for want of better terms, ignorant again …

MS. TIPPETT: To see unexpected likenesses, metaphors.

MR. MULDOON: That’s right. And we continue to do that. But we tend — whether or not we write poetry, we continue to see these unexpected connections. And that, of course — it’s odd that it doesn’t have more of a place in the world, because that idea of the connection is quite central, of course, to who we are and how we operate. We love to make connections.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: And it’s what makes us feel good in the world. It’s what sends our endorphins buzzing around or whatever they do.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, yeah.

MR. MULDOON: So, somehow, in the poetry business, let’s say, other things begin to push in. One of them is that poetry of a certain kind is introduced into the head. What passes for poetry tends to end up as merely Dr. Seuss. Now, I love Dr. Seuss. I think he’s fabulous. I think he’s fabulous. But if you ask an eight-year-old to write a poem, she’ll come up with the tadpoles. You ask a 15-year-old to write a poem, and it’s sort of sub-sub-sub-Seuss.

MS. TIPPETT: Interesting.

MR. MULDOON: And something has happened. And I think a large part of this falls on the shoulders of educators in the broadest sense — the parents, the teachers. “This is poetry.” And of course it’s one form of poetry. But my own view is that children should be — insofar as we have any [laughs] control over them at all, and of course, as parents, we know we have less and less, as it should be — but in some sense, I think we should be introducing them to Robert Frost, and Lord Byron, and Tennyson, and Marianne Moore, and Elizabeth Bishop, and Emily dinkinson, and John Donne. We should be giving them not, quote-unquote, children’s poetry, but poetry.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: I think it’s much, much more effective to give them Mozart and Handel and whoever. I mean, is that grown-up music, children’s music? It’s music.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: Give them music. And I do think that we are what we eat. And if you are given a completely Seussian diet — as I say, I love Seuss, but if that’s all you’re eating, there are going to be problems. And that compounds the problem. There are other aspects. Again, poetry is, perhaps, often overly taught. When the teacher comes around to teaching poetry, I think in many schools, not all, she herself is actually quite nervous about poetry. She has to show the child the intricacies of the poem, the great unknown territory of the poem that, without the teacher, the child would get lost and wouldn’t last a day, would die of exposure in the poem…

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] Right, right, right, right.

MR. MULDOON: …without this fantastically prepared guide through the poem. And I think as teachers we all run the risk of wanting to show how smart we are, and it’s part of what happens, then, is that the child is convinced that a poem is never about what it seems to be about. It’s always about something else. It’s always encoded in some way.

MS. TIPPETT: Inexplicable.

MR. MULDOON: Inexplicable. It’s never about what it is, what it seems to be about.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s beyond us.

MR. MULDOON: It’s beyond us. And the fact of the matter is it is not beyond us. It’s right there. And what has tended to happen, and one of the reasons why there may be a little difficulty with the reading of poetry — in most cultures, actually, not only this — is that we have neglected to accept that to listen to music, you have to learn to listen to music. Now, we learn to listen to music by having the radio on 24 hours a day, by being bombarded by it in the mall, everywhere. So we’re actually quite au fait with how music works.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: We’re absolutely au fait with how film works. When we go to see the new, whatever, blockbuster, we are very well equipped to watch it, and we know what it’s alluding to, if anything. We know its structure. We recognize a flashback. We are able to come out of it and say, “You know, along with Rotten Tomatoes, I give that 80.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. MULDOON: “Along with Siskel and Ebert, it’s two thumbs up.”

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: Or “two thumbs down.” With poetry, we have not had that exposure. It’s as simple as that.

MS. TIPPETT: And you’re the poetry editor of The New Yorker.

MR. MULDOON: So I’m told.

MS. TIPPETT: Which infiltrates poetry in along with other kinds of writing and thinking and reviewing. As you said, it’s next to the film review.

MR. MULDOON: It is, and that’s one of the great things about that magazine.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. It’s very rare in America.

MR. MULDOON: It’s a fabulous magazine in many ways, including that way, and — we have a difficulty, though. We have a difficulty. And the difficulty is that we’re able to carry only 100 poems a year.

MS. TIPPETT: What does “able” mean? Because of room constraints?

MR. MULDOON: Yes. And, you know, there are two poems a week in the magazine usually. I’d say 100 a year. And we know all too well that there are more than 100 good poems being written in this country. Many more. Many, many more. So what I think would be fabulous would be if The New York Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, the L.A. Times, whatever, The Boston Globe, if these newspapers were able — if they could just have at least a poem, if not every day, every couple of days, once a week. It would — actually, they wouldn’t have to pay anything for it. They’d need to pay somebody to keep an eye on it, I suppose. But it would be — to get the sense that poetry is not special.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: That it’s there as a — just another feature and factor and fact of life.

MS. TIPPETT: Amidst all of our other ways of communicating, writing …

MR. MULDOON: Amidst all of — or being.

MS. TIPPETT: And being.

MR. MULDOON: It would be lovely to think that people might be discussing the poem in the paper the way they’d be discussing the Mets score.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: You know?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: Having said that, I really don’t want to be part of too many more discussions of, you know, the demise of poetry, the poor state that poetry is in. I mean, frankly, there are a lot of people writing poetry. There aren’t enough reading it. But it’s not necessarily an art form that is at death’s door. I just don’t subscribe to it.

MS. TIPPETT: I don’t think so, either. My experience, when we put poetry on the air in this radio show, is that people respond to it like they were starved for it all along, and they didn’t know it. It’s not even just — it’s not a discovery. They understand it wasn’t even optional.

MR. MULDOON: Well, I think that’s why it’s really a responsibility of the media outlets, as we call them, I guess — it seems like a crass term — but it’s our responsibility to give people that opportunity.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I want to tell you, I’m one of these people who cannot abandon the printed page. I still do all my reading in books.

MR. MULDOON: Same here.

MS. TIPPETT: However — and even my magazines. But I stumbled upon the fact that when you read The New Yorker on the iPad, you can listen to the poet reading the poem, which is brilliant. So it’s one of the few places I’m now going, to this mobile device, for the reading, because it’s both of those layers of the poem, which is so wonderful.

MR. MULDOON: Well, you know, it’s — I’m delighted you enjoy that. And that, indeed, is the ideal way to experience a poem is a combination of being able to read it and being about to hear it. Because there’s always something of interest in how, in particular, the person through whom it came into the world delivers it into the world. There’s something revelatory, again, about having that experience. And we’re — our first experience of poetry was, if we were lucky, was an auditory one. And while not all poems absolutely function as aural experiences — of course they don’t, there are many that operate more for the eye — most of them do. And, mostly, there’s something rewarding to be had from that experience, I think.

[music: “My Funny Valentine” by Ahn Trio]

MR. MULDOON: One good turn deserves a bird in the hand. [laughter]

A bird in the hand is better than no bread.

To have your cake is to pay Paul. [laughter]

Make hay while you can still hit the nail on the head. [laughter]

For want of a nail the sky might fall.

People in glass houses can’t see the wood

for the new broom. [laughter]

Rome wasn’t built between two stools.

Empty vessels wait for no man.

A hair of the dog is a friend indeed. [laughter]

There’s no fool like the fool

who’s shot his bolt. There’s no smoke after the horse is gone. [laughter]

Thank you. [laughter] [applause]

[music: “Silk Tears” by Simon Shaheen & Qantara]

MS. TIPPETT: Find Paul Muldoon reading this poem, “Symposium,” and others at onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Silk Tears” by Simon Shaheen & Qantara]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a conversation with verse with the poet Paul Muldoon. He’s the poetry editor of The New Yorker magazine, and a professor at Princeton University. He spent a day of conversation, food, and public reading at our studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis.

MS. TIPPETT: I lived for a while in divided Berlin in the 1980s, when the wall divided the city, and experienced a place where poets were heroes. People didn’t have a lot of what makes life meaningful or comfortable handed to them, but they did carve out lives of dignity and beauty and integrity. And in those spheres, poets were such important people. Poetry had a — it was cherished, and it was also dangerous, and these poets sometimes got expelled. And I know that — I was last year at a gathering where there were poets from places like Sierra Leone. I mean, it’s true across human history that in dark times, often, that this need in us for poetry, I think, rises to the surface, becomes more evident. Now, you are often called a poet of “the Troubles,” that you came out of Northern Ireland’s trauma. I wonder how this might speak to where this country is right now, in this early 21st century with so many large, open questions.

MR. MULDOON: I’m glad you think so.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: Not everybody thinks that.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh.

MR. MULDOON: A lot of people think the deal is done here, that America has arrived at the condition of being America.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, well, we’re human beings, so the deal is never done, right? [laughs]

MR. MULDOON: Well, I think so.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: But other people — for example, on the poetry front, I think a lot of people continue to think, well, poetry actually happens in one of these more interesting places.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Well, so my question to you is — and you’re working with students, you’re working with young people, so here. How do you think about the role of poetry in hard times and in moments of upheaval, because this is a moment of upheaval, whether we are reckoning with it or not?

MR. MULDOON: Do you mean in the U.S.?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, in the U.S., it’s true.

MR. MULDOON: Well, yes, I mean, as I say, for people to recognize that it is, I think, is probably — I think a lot of people are reluctant. Despite all the evidence, despite what they see on the TV news, if they watch the TV news — and there are many reasons why they could do well not to watch the TV news, because so much of it is bunkum, and so little of it is …

MS. TIPPETT: And demoralizing and paralyzing.

MR. MULDOON: So little of it is news. But one would like to think that poetry and the other arts would help us, to some extent, make sense of these things. And I’m sure there is actually a certain amount of writing now that represents, for example, the black experience in this country in a way that is very refreshing, and is very welcome. Will that stop policemen shooting black men at will, it seems, in some cases? I don’t know. One of the interesting things about poetry and poets is that we are often called upon to do the work, put crudely, that should be done by other agencies. You know, we don’t necessarily — generally, at least — ask painters, or philosophers, or composers, or many other forms of artiste to help us solve our societal problems.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. [laughs]

MR. MULDOON: And it’s partly because, of course, we think there’s — and understandably so — that poets are, indeed, special cases, and that they have some kind of extraordinary insight into how things work, which in ways they do. But I don’t know if we should be expected to come in and solve society’s problems. It’s part of an idea that’s been presented by poets themselves, of course, as well as readers, that, somehow, poetry may be a form of salve, of salvation, that it’s a form of succour, S-U-C-C-O-U-R…

MS. TIPPETT: O-R.

MR. MULDOON: …succour, in the world.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, but I wonder if that moment of desperation where literalistic, can-do, pragmatic Americans come into that moment of acknowledging one’s helplessness and ignorance…

MR. MULDOON: I’d love to see it.

MS. TIPPETT: …and turn to poetry as one of the resources.

MR. MULDOON: As one of the resources?

MS. TIPPETT: As one of the resources for courage, and bringing some beauty, and perhaps some playfulness, and some reflection of the unconscious.

MR. MULDOON: I think that’s right. It would be great if that were to happen. There’s a little bit of a problem, though, which is, in the popular imagination, poetry is all salve. It’s all beauty, things of beauty, beauty in the world. And unfortunately for those who hold that position, if one actually looks at poetry, one realizes that, more often than not, it’s a representation of ugliness, of the difficulties of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: The complexity …

MR. MULDOON: The complexity of the world. And I think it is necessarily so, because that, unfortunately, is the larger part of what we meet. And, again, I think it’s too much for us to go to poetry, or any of the other art forms, expecting them to bring us merely beauty.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, or to be merely uplifting.

MR. MULDOON: And to be merely uplifting.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: I read somewhere recently about — I think it was Bruce Springsteen who was talking about how many of — I hope I’m not misquoting him — I think was himself talking about how many of his songs are constructed, and they begin with some sense of desolation, and then some sense of uplift, or whatever. But desolation is part of the deal.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that’s a good example, too, because I don’t think this — whatever the uplift is doesn’t negate the desolation, right? It’s still there.

MR. MULDOON: That’s right. That’s right. And I think, as human beings, we have to live amidst this terrific morass, mess of information, and these various upheavals in the world, the various assaults on us — physical, intellectual — that push in on our lives. And to find ways of — a phrase I use sometimes — being equal to that, being equal to that pressure. It’s very difficult. But we have to do it.

[music: “The Crow in the Sun” by Daithi Sproule]

MR. MULDOON: In Armagh or Tyrone

I fell between two stones.

In Armagh or Tyrone

on a morning in June

I fell between two stones.

In Armagh or Tyrone

on a morning in June

in 1951

I fell between two stones.

In Armagh or Tyrone

on a morning in June

in 1951

I fell between two stones

that raised me as their own.

[music: “The Crow in the Sun” by Daithi Sproule]

MS. TIPPETT: Paul Muldoon with an excerpt from his poem “The Outlier.” I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

MS. TIPPETT: Song and music are important to you. You have a rock band, is that right?

MR. MULDOON: Well, I do try to write lyrics, and I’ve tried to write lyrics for various bands. Bands come and go. And I just, I love music. And I was — like many of a certain age, 64 now — when I heard “When I’m 64” from the Beatles, it’s, I suppose, like everyone else, perhaps, themselves, they were thinking, that’s a long way down the road.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. [laughs]

MR. MULDOON: But the truth is that has been part of our — part of our being, actually. And, in fact, rock ‘n’ roll is as much, I would imagine — I would be surprised if it weren’t the case, if it’s not as much an inspiration to my writing life as Theodore Roethke, or any of the other writers whose names begin with R, [laughs] Robert Frost. We’re almost indivisible from it. It’ll be very hard to distinguish oneself from all those noises that have been in the air for so long.

MS. TIPPETT: I think you make such an important point that poetry and song are so much — to the extent that there’s a border between them, it’s very porous. And, in fact, that — here I am quoting you at yourself again.

MR. MULDOON: That’s all right. Go ahead.

MS. TIPPETT: But someplace else, you talked somewhere about the fact that there’s kind of a modern disdain of poetry that rhymes. It’s not necessarily in fashion, or it goes out of fashion again and again. But that, in fact, in song, what we have is rhyming poetry, and that that continually keeps humanity in touch with that, whether the official world of poetry is doing it or not. It’s so interesting. It’s a way to think about how poetry is, in fact, woven into our lives in ways that we don’t imagine.

MR. MULDOON: Of course it is. And poetry comes in all sorts of forms, all kinds of forms, all shapes, all manner of ways. And I think if we take into account all the manifestations of poetry in the world — including some in prose fiction, by the way, and nonfiction — with the ways in which it goes back to some of its earliest sources, the riddle, the prayer, the charm, the incantation, which, of course, were all forms of poetry in some societies, and continue to be, I think, in many. If one accepts, in one’s expansiveness, rock ‘n’ roll, and rap, and country music.

MS. TIPPETT: This is wonderful. I want to just ask a couple more questions. It’s …

MR. MULDOON: Do you think you have stuff? I have no idea what…

MS. TIPPETT: Absolutely, absolutely.

MR. MULDOON: …if you have stuff you might like. I have no idea.

MS. TIPPETT: So much. I wanted to — you can see I always have far too many notes.

MR. MULDOON: No, no, not at all, that’s good.

MS. TIPPETT: I reached out to a friend who is in Northern Ireland, who actually heads the Corrymeela Community.

MR. MULDOON: Oh, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And he’s a poet, in addition to being a peacemaker. And I wanted to read you — where is it — what he said to me. I told him I was interviewing you, and he said — and this, I think, goes back to what you said a moment ago about what the poet can be expected to do and shouldn’t be expected to do. He said, “Muldoon has never been a poet that I turn to to soothe the heart, more to trouble the waters and to electrify the possibilities of form and limits.”

MR. MULDOON: Well, he’s a wise man because…

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] Obviously.

MR. MULDOON: …if he wants something to soothe the heart, he needs to go somewhere else.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: Perhaps to the scriptures, or any of the great texts of the great organized religions.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MULDOON: They’re in the business, some of the time, of doing that. Though I’d say that vast tracts of the Hebrew Bible, or the Old Testament, as some refer to it, are hardly likely to soothe the heart.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Well, desolation is big in those texts, as well.

MR. MULDOON: Absolutely, yes, absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. MULDOON: I wouldn’t go there for comfort, necessarily, either.

MS. TIPPETT: No.

MR. MULDOON: I’d go for a cup of cocoa.

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] He was telling me that in the Irish language, the words for poem and poet have different etymologies.

MR. MULDOON: Yes, I mean, the word for file — the word for “poet” is file.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, for “poet,” right.

MR. MULDOON: Of course, the word “poet,” itself, from the Greek, means “a maker.” So it’s possible that the “f-” bit of it is related to “fact,” “factoring,” or something, “making,” “fabricating” as a kind of Indo-European — I don’t know. I’m probably making that up. But the word for a poem is dán, D-A-N. And there’s another word in Irish, dán, which means fate. And it could be that there’s a connection between those two.

MS. TIPPETT: Between the poem connected to fate, having a fatefulness …

MR. MULDOON: Fate, or being — you know, one of the things I’m fascinated by — and as I say, I’m not certain of this etymology — but I am nonetheless interested in the idea of that sense that we have when we read a poem that there’s something inevitable about it, that it was fated to be like this. It was never meant to be any other way. This is the only way it can be. It can’t be translated. We can’t give a précis of it. We can’t really describe it in terms other than its own. It was always meant to be. It came to us through a poet, and it’s like this. And so that sense of the fatedness, the inevitability, and perhaps even the eternity of the poem.

MS. TIPPETT: Let me just ask you …

MR. MULDOON: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: This is a large question…

MR. MULDOON: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: …and I’m not asking you to answer it, but …

MR. MULDOON: I’ll give you a little answer.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. The question is, how would you think, how would you start to talk about — because this is an answer that would have no end — what your life as a poet, now that you’re 64, as the song predicted, [laughs] but you never thought it would be about you — what has your life taught you about, revealed to you, about what it means to be human? How would you start to start to think about that? Maybe what you’re continuing to learn.

MR. MULDOON: What it means to be human?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. That large, existential question.

MR. MULDOON: Well, of course when one’s 16 and looking at the 64-year-old, one imagines that he knows something, is certain of something, that his experience really adds up to something, that his experience may be brought to bear on some — not any task, particularly whatever area of focus might be, if he has one. And in my case, the thing I know now, and I’m sure this is true of many, is how — not even how little I know, but how I know nothing, in fact. You know? And I thought, I know nothing about anything. And the things that we thought indeed were verities, I think I’m right in saying that, you know, ranging from Pluto being a planet…

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] Right.

MR. MULDOON: …through E equalling MC squared, about which there seems to be some question, never mind the notion of the universe, which is a phrase we used when we were — from time to time. In fact, I think there was a Catholic newspaper called The Universe. At that stage, I’m pretty sure I’m right in saying we had no idea that it should really be called “the universes,” the millions, or is it billions, of universes. So I think to try to take that in is almost impossible, yet, I suppose, we must try, on this tiny planet, which I have sailed around, circumnavigated — to be set down here, however, to try to, one would hope, do our best while we’re here. And I think, really, our impulse is to do our best, however often we might lose sight of it, and try to be kind-ish to one another while we’re still here.

[music: “Hypnotized” by Ani DiFranco]

MR. MULDOON: The day our son is due is the very day

the redknots are meant to touch down

on their long haul

from Chile to the Arctic Circle,

where they’ll nest on the tundra

within a few feet

Of where they were hatched.

Forty or fifty thousand of them

are meant to drop in along Delaware Bay.

They time their arrival on these shores

to coincide with the horseshoe crabs

laying their eggs in the sand.

Smallish birds to begin with,

the redknots have now lost half their weight.

Eating the eggs of the horseshoe crabs

is what gives them the strength to go on,

forty or fifty thousand of them getting up all at once

as if for a rock concert encore.

[music: “Fitzcarraldo” by The Frames]

MS. TIPPETT: Paul Muldoon reading his poem “Redknots.” You can hear or watch him reading this and other poems at onbeing.org.

Paul Muldoon holds the Howard G.B. Clark chair in the Humanities at Princeton University. He’s been poetry editor of The New Yorker since 2007. And he is the author of 12 major collections of poetry, including Horse Latitudes, Hay, and his latest collection, One Thousand Things Worth Knowing.

[music: “Fitzcarraldo” by The Frames]

MS. TIPPETT: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Annie Parsons, Tony Birleffi, Marie Sambilay, and Tracy Ayers.

Special thanks this week to Mark Conway and the College of St. Benedict’s Literary Arts Institute, and to Farrar, Straus, and Giroux for permission to use Paul Muldoon’s poetry.

Our major funding partners are:

The Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the front lines of social change worldwide at fordfoundation.org.

The Fetzer Institute, fostering awareness of the power of love and forgiveness to transform our world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, contributing to organizations that weave reverence, reciprocity, and resilience into the fabric of modern life.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

And, the Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections