Susan Cheever and Kevin Griffin

The Spirituality of Addiction and Recovery

Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson once said that the program he helped create is, “utter simplicity which encases a complete mystery.” Our guests reflect on the Twelve Steps and how they resonate in their personal stories and in Buddhist and Christian teachings.

Image by Matthew Henry/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

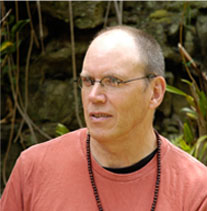

Kevin Griffin is a Buddhist dharma leader and writer. He's the author of One Breath at a Time: Buddhism and the Twelve Steps.

Susan Cheever is the author of several books, including My Name Is Bill, a biography of the co-founder of AA.

Transcript

May 15, 2008

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson once said that the program he helped create is “utter simplicity which encases a complete mystery.” This hour, we’ll explore the spiritual foundations of addiction and recovery. Kevin Griffin reflects on the consonance of Buddhist teachings and the Twelve Steps in his experience. Susan Cheever has written a biography of Bill Wilson, and she knows addiction and recovery in her own life and that of her father, the late fiction writer John Cheever.

MS. SUSAN CHEEVER: There’s something mysterious at the heart of Alcoholics Anonymous, and whether you call it God or not, there’s something mysterious there that makes people whole again.

MR. KEVIN GRIFFIN: Addiction was just an extreme case of exactly what the Buddha was saying was the cause of all our problems.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Over 20 million Americans — nearly one in 10 over the age of 12 — suffer from alcohol or drug addiction. A comparable number battle other forms of addiction, sometimes simultaneously, including gambling, sex, and food. Until the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous in the 1930s, addiction was a nearly always fatal affliction, immune to the best methods of psychology or medicine. In seven decades since, the Twelve Step program of AA has saved or repaired the lives of millions across the world. And it has done so in part by analyzing addiction as a spiritual malady. The Twelve Steps’ insights into the human condition and its disciplines for spiritual healing translate across the world’s cultures and traditions.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “The Spirituality of Addiction and Recovery.”

Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson once said that the program he help create is “utter simplicity, which incases a complete mystery.” AA formed organically from the experiences of alcoholics themselves, forged in fellowship with each other, and condensed in 12 steps and 12 traditions. In 1939, the movement’s first 100 or so members laid out what they had learned in a guiding text, The Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Here’s a recording of Bill Wilson, who died in 1971, reading from a chapter called “How It Works”:

MR. BILL WILSON: (recording of the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous) “If you have decided you want what we have, and are willing to go to any length to get it, then you are ready to take certain steps. At some of these we’ve balked. We thought we could find an easier, softer way. But we could not. With all the earnestness at our command, we beg of you to be fearless and thorough from the very start. Some of us have tried to hold on to our old ideas, and the result was nil until we let go absolutely. Remember that we deal with alcohol — cunning, baffling, powerful. Without help, it is too much for us. But there is one who has all power. That one is God.”

MS. TIPPETT: In such language, it’s possible to imagine a quasi-religious movement. Later in this hour, I’ll speak with Kevin Griffin, who’s found life-giving resonance between the Twelve Steps and Buddhism

My first guest, Susan Cheever, has written widely about her own experience with addiction and recovery, and that of her father, the late fiction writer John Cheever. She’s also written a biography of Bill Wilson. I interviewed her shortly after the 2004 release of that book. Even as she describes the significant Christian influence in the formative years of AA, Susan Cheever also points out that Bill Wilson was never a conventionally religious person. He grew up in an age in which churches were a driving force in the temperance movement behind Prohibition, a legal ban on alcohol in the United States that lasted from 1920 to 1933.

But in that same era, in the New England of Bill Wilson’s childhood, the writings of American icons like Thoreau and Emerson were subtly affecting traditional ideas about God and faith. Susan Cheever suggests that these shifts in the American religious imagination made the accessible spirituality of AA possible.

MS. CHEEVER: What was happening in the 1850s and ’60s, before the Civil War in New England, contributed in a very direct way to what Bill breathed in and out with the Vermont air at the turn of the century. And I think the whole sort of overturning of the idea of God as an authoritarian male figure, that the divine could exist in the song of a wood thrush or the reflections in a pond, and that it could especially — this was especially Emerson’s point — that it could exist in other human beings.

And, of course, one of the things that Bill Wilson, in his genius when it comes to spirituality, understood was that it’s a mistake to prescribe faith for another person, that you can say to another person, ‘You must have some kind of faith,’ as Alcoholics Anonymous sort of does, but you cannot say to another person, ‘You must have faith in X.’ It can reside wherever you say it resides as long as it’s not you.

MS. TIPPETT: What does that say about the spirituality of addiction itself?

MS. CHEEVER: There’s a wonderful letter. In 1961, Bill Wilson wrote a letter to Carl Jung, and Jung had treated a man who ended up being one of the original men in Alcoholics Anonymous. And this man, Roland, had often talked about Jung, and Jung writes back to Bill, and he says, ‘That’s right.’ He says, ‘I despaired of treating alcoholics, because I knew that they couldn’t get better unless they had some kind of religious experience.’ He called it religious. And then he came out with this wonderful phrase. He said, it has to be “spiritum contra spiritus.”

MS. TIPPETT: He draws that semantic kinship between spirits, as in alcohol, and the human spirit, but more than a semantic kinship.

MS. CHEEVER: Exactly. You know, many, many people in Alcoholics Anonymous will say that alcoholism, that drinking is a low-level search for God. In other words, that the role of the spirit in the abuse of spirits is profound in its multiplicity. And I think, you know, Bill Wilson understood that very well. He was a man who had turned against religion, who had walked out of church, who did not want to be told what to do, who had walked out of church specifically because they asked him to take a temperance pledge. And he just thought it was a bunch of hooey. However, he was a man who was extremely open to ideas.

MS. TIPPETT: So the identification of this as a spiritual malady was more important than prescribing a spiritual treatment?

MS. CHEEVER: Exactly. I mean, he says somewhere in the writing that he’s not going to give any alcoholic any rules, that everything he writes — I think it’s in the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, which he wrote, you know, later — is just suggestions. You know, he’s just a profoundly tolerant human being. And, you know, you see it in his personal life in the way he dealt with his family, but you also see it — you know, the program of Alcoholics Anonymous is imbued with this tolerance. It reeks of it. The openness of it is so astonishing to me, and that’s why, you know, I don’t mean to be dancing around, but it’s hard to pin down what faith is in terms of what Bill Wilson laid out as the program of Alcoholics Anonymous because he was so canny about not laying it down. I mean, he really wanted to make it a moving target.

MS. TIPPETT: You mentioned this in passing that he did have this very dramatic experience of what I think he called God, of blazing light, right?

MS. CHEEVER: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: And a mountaintop. And didn’t he stop drinking on that day?

MS. CHEEVER: Yes. There’s no question that in his story, he was a man desperate to stay away from a drink. And over this period of about 10 or 15 years, he put together, one piece at a time, trial and error — mostly error — the things that helped him stay away from a drink. So he would get, for instance, that if he spoke to another alcoholic he had a better chance of not drinking. And then he would think, ‘Oh, now I have it,’ and then he’d drink again, right?

Or he would get, as he got from Dr. Duncan Silkworth, the idea that alcoholism was a disease, that it wasn’t a willpower problem, that he was allergic to alcohol, and that was why he couldn’t drink. And he’d think, ‘OK, now I’ve got it,’ you know? And then he’d drink again. But slowly he was getting it. And the last piece, which he got during his fourth hospitalization at Towns Hospital on Central Park West, was a direct, extremely dramatic experience of God, where Bill Wilson, just feeling helpless and, you know, hopeless, fell to his knees and cried out, “God help me.” And he had, you know, the room was suffused with light, a divine light. And he said, “So this is the God of the preachers.” I mean, for him, there’s no question that he had, like St. Paul on the road to Damascus, that he had a religious epiphany and that after that experience he never drank again. But, as I keep saying, and I hate to repeat myself, he understood that that wasn’t going to happen to everybody.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, and I will say I’m a little bit surprised to — I’ve been interviewing a few people for this trying to think about the spirituality of recovery.

MS. CHEEVER: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: And I have actually heard two other stories that are very similar to that one. One of them was an Indian man, who — I mean who also — where the room opened up and it was not God it was his ancestors, but it was of a mystical experience that was very dramatic and a moment of healing in a way from which he never could turn back again. I mean, did you have a dramatic experience before you got into recovery, anything like that?

MS. CHEEVER: I don’t — I didn’t, no, I mean I didn’t have, I mean, I would certainly remember if I had that, that quality of experience.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, yeah.

MS. CHEEVER: But no, I don’t think I’ve ever had a direct experience of the divine. Indirect sure, but — I mean, I think of faith, for me at least, as not something I have. It’s something I aim toward, I struggle towards. It’s something I try to point myself toward, but it’s not something I ever, ever have, you know, the way I have my keys in my pocket. But that doesn’t make it any less real.

Author Susan Cheever. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, we are exploring spirituality, addiction, and recovery.

MS. TIPPETT: Author Susan Cheever. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, we are exploring spirituality, addiction, and recovery.

Susan Cheever has struggled with addiction in her life, as did her father, the late fiction writer John Cheever. Her biography of AA co-founder Bill Wilson is called My Name is Bill. That title refers to the core principle of anonymity that guides Twelve Step philosophy. It begins at every local meeting, where people tell their stories and listen to others identifying by first name only. And such basic practices, as Susan Cheever tells it, have also changed her sense of the meaning of faith.

MS. CHEEVER: You know, Alcoholics Anonymous is a very intimate way of living. And I think that for anybody who has faith, when they go into Alcoholics Anonymous that faith becomes much more intimate. In other words, it’s one thing entirely to believe in a God who controls all, and it’s another thing to believe in a God who really cares whether or not you drink that tequila shot. And it makes whatever your God is, whoever your God is, it makes it very, very personal and intimate. And I think that’s, you know, one of the amazing things that Bill was able to do. He was able to take faith with a capital F, and God with a capital G, and bring it right into people’s hearts and minds so that that faith becomes, you know, whether you’re an alcoholic or you’re addicted to food or you’re addicted to heroin, God comes between your mouth and your hand. And that’s just so amazing, because usually faith is something out there waiting for you, you know? Or, I mean, usually these things are thought of, or conventionally these things are thought of as very much outside the scope of what happens between your mouth and your hand.

MS. TIPPETT: What is it about alcohol that can force people so close to this intimacy that you’re describing?

MS. CHEEVER: You know what? I think it’s not just alcohol. I think it’s all addiction. There is something about addiction, you know, just thinking about my own life, it comes from fear. This is just from me. You know, this is not from any other addict. But it’s kind of fear-based. You know, there’s kind of lack of trust. I mean, I certainly can talk about it right now in terms of food. I will say I’m going to eat two soy cutlets for lunch and then around about 5:00, I think, ‘Huh! There’s never going to be any more food in my life. I’m going to starve to death, and the cupboard’s going to be bare, and there’s going to be nothing in the fridge, and the markets are going to be shut.’ And you see this fear, you know, when people hear there’s a hurricane coming, they line up at the supermarket as if — you know, I think that fear is very much present in human life. But, so then, instead of waiting for dinner, I have to have whatever I have to. Do you see what I’m saying?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Yeah.

MS. CHEEVER: It’s a lack of trust. It’s an inability to just think, ‘You know what? It’s going to be all right.’ And, like, who was that, St. Julian?

MS. TIPPETT: Julian of Norwich.

MS. CHEEVER: Who said, “All will be well.”

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MS. CHEEVER: “All things will be well.”

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MS. CHEEVER: It’s the opposite of that. It’s a kind of panic. It’s, ‘There’s never going to be any more food.’ ‘There’s never going to be another drink.’ ‘There’s never going to be enough for me.’ And in my experience, addiction comes out of that, that wanting, that hunger. And that’s very intimate. In other words, you won’t get a lot of people on the radio even copping to this stuff. And, you know, therefore, to put that into remission, or to calm it down, you have to have a faith or a system or whatever you’re going to call it that’s very intimate as well, because it’s private, it’s personal. And I think — you know, I often wonder why we live in a culture that is so blind to alcoholism and I think that’s one of the reasons, it’s so private, it’s so personal what a person drinks or what they don’t drink.

And I think that’s partly also the basis, you know, of Bill’s understanding of the importance of anonymity is that anonymity sort of protects that incredibly intimate private nature of addiction and, you know, the treatment for addiction, of that change of heart. You know the human heart is such a, such a private and frightening place. But I also think that it — to me, one of the greatest — I don’t know what the word is — one of the greatest foundations of spirituality is what Bill called anonymity and, you know, what Christ called humility. And I’m sure that Buddha also had a name for it.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to ask you about a couple of the other spiritual disciplines that are a part of AA, of the Twelve Steps.

MS. CHEEVER: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Storytelling, you know, why — why is that a spiritual discipline? And you are a storyteller, so I really want to hear your thoughts on it.

MS. CHEEVER: I think storytelling is the whole game. You know, if I say to you, ‘You’re an alcoholic,’ you’re going to say, ‘Goodbye.’ If I say to you, you know, ‘This happened to me, and this happened to me, and this happened to me, and this happened to me, and then this happened to me,’ there might be something in that list of things that happened to me where you go, ‘You know what? That happened to me, too.’ And that’s, you know, the best way of communication that we have.

MS. TIPPETT: So what’s spiritual in that?

MS. CHEEVER: Well, to me, you know, the most spiritual thing anybody can do is connect with another human being. And that’s how we connect: storytelling. Sometimes we’re connecting with ourselves, but I think in Alcoholics Anonymous, the energy of this and the ability that we all have, the incredible eloquence that we all have about our own lives is harnessed in the service of connecting one alcoholic to another.

MS. TIPPETT: And that gets at another discipline or aspect of Alcoholics Anonymous, a recovery that you can also find in all the religious traditions, just this value of community, of relationship, in AA.

MS. CHEEVER: Well, I think what people get in AA is for an alcoholic who has not been able to stop drinking, to be able to stop drinking is one of the most miraculous things that anybody ever sees. And it isn’t just miraculous for the alcoholic, it’s miraculous for the alcoholic’s family and everyone around them. I mean, people in Alcoholics Anonymous do have a change of heart. And it’s ultimately mysterious. In other words, we can break it down and talk about storytelling, and this and that, but ultimately something happens to people who go to Alcoholics Anonymous with all its lack of rules and regulations that enables them to stop drinking a day at a time.

And that really, I mean, this was my first exposure to Alcoholics Anonymous was when my father went. And he didn’t want to go. He’d been to meetings. He didn’t like them, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And finally he went to rehab, and he came out a different person. When he went into rehab, he was just this sour — he was ready to die. He just sat around criticizing all the time. You could just tell he was miserable. And so he made everybody else miserable. And he came out of rehab and started going to AA meetings, and he was a completely different person. He was totally engaged with the world. He suddenly wanted to learn how to work the dishwasher so that he could take care of himself. You know, he was funny, he was empathetic, he was concerned. You know, he was involved in other people’s lives. I mean, he had a change of heart that blew us all away.

And so, to my mind, you know, there’s a countervailing force to addiction. And you see it at work in people who go into Alcoholics Anonymous and go into recovery. And, you know, maybe the brain chemistry changes. I’m sure it does. And maybe it has something to do with the power of the group. I’m sure it does. But there’s something mysterious at the heart of Alcoholics Anonymous, and whether you call it God or not, there’s something mysterious there that makes people whole again. And to my mind, that’s a pretty good argument for faith.

MS. TIPPETT: Susan Cheever is the author of many books, including My Name is Bill: Bill Wilson — His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. Her new book, Desire: Where Sex Meets Addiction, will be published this fall. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, author and Buddhist meditation teacher Kevin Griffin. He has found the Twelve Steps and core Buddhist insights to echo and inform one another to profound effect.

Read passages from Susan Cheever’s father, the late author John Cheever’s writings about his addiction and recovery at speakingoffaith.org. Also find there the renowned psychiatrist Carl Jung’s letter to Bill Wilson, about spirituality and the treatment of alcoholism. Download free MP3s of this program and my entire unedited interview with Susan Cheever. And we’ve just won a Webby, the Oscars of the Internet. Five-word acceptance speeches are a tradition at the awards ceremony that our online editor, Trent Gilliss, will attend in June. Send us your ideas for what those five words should be. Go to SOF Observed, our staff blog, and comment on Trent’s post about winning the Webby. Help us out at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, exploring the spirituality of addiction and recovery

My next guest, Buddhist meditation teacher Kevin Griffin, has found Twelve Steps spirituality and Buddhist insights to echo and inform one another to profound effect. He’s written, “I need the wisdom of the Buddha to absorb the realities and mysteries of life; and I need the voices of a thousand alcoholics and addicts to keep me on track today.”

Like my first Susan Cheever, Kevin Griffin has chosen to break from the Twelve Step tradition of anonymity by writing and speaking publicly and in the media about his experience of recovery. He grew up in Northern California in the 1960s and ’70s and became a musician at a young age, a story he tells in part in his book One Breathe at a Time: Buddhism and the Twelve Steps. Kevin Griffin struggled with addictions to alcohol, drugs, and sex until he was 35 years old. Even as, for some of those years he was a health-conscious vegetarian and a spiritually engaged person.

MR. GRIFFIN: In some ways my spiritual search was another search for a fix.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: For another drug. And I’ve seen people use it that way, not just me, you know, people who, you know, who don’t relate as alcoholics or addicts, who get very caught up in having particular kinds of experiences. What I realized after I got sober was that I was overlooking the fundamental morality foundation of any kind of spiritual growth. And that came partly out of my own willful ignorance and partly because the way Buddhism was being presented in our culture in the ’70s, was they were not emphasizing that aspect of it. Many of the people who got into Buddhism early on got there through LSD.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right. And, I mean, putting your story in the context of those times is — there’s also this line that you talk about walking, even music like “Strawberry Fields” or Jimi Hendrix, those almost kinds of transcendent spiritual experiences that were connected with drugs and kind of exalted and very powerful, right?

MR. GRIFFIN: Well, yeah. I mean, “Strawberry Fields nothing is real,” I mean that’s a very powerful, spiritual statement, and it’s in the context of music that’s kind of trying to induce that hallucinogenic state.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. GRIFFIN: So there was a lot of confusion about it. There still is.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, and so talk to me about, tell me a little bit of the story about your turning point. I know that it’s not one moment; it’s a long passage of life. But what happened to start it to move you — what happened to really finally move you towards recovery, towards sobriety?

MR. GRIFFIN: Well, so I was trying to find my way out of suffering, basically. I identified that suffering mostly around depression, but it was certainly — really more complicated than that.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. GRIFFIN: And, yeah, basically I felt like I tried everything and nothing worked, you know, going so far as to go on a three-month silent retreat. If that doesn’t fix you, what will, kind of. So that I then lost myself by turning myself over to this kind of homeless guru, and that’s when I really kind of bottomed out, which was three years before I got sober. And I started to kind of rebuild my life, and it is mysterious in a way. I met somebody who was sober, a musician, and I was playing with him. And that gave me a vision of sobriety, where I thought, ‘Oh, OK. He’s kind of cool,’ you know, ’cause you think that anybody who is into a 12-step program is just either a looser or, you know, some…

MS. TIPPETT: That’s what you thought, back then?

MR. GRIFFIN: Yeah, and — and the only person I’d ever known who was sober was a friend of my parents, you know, so I didn’t have any associations with my generation.

MS. TIPPETT: Did you get into an AA, a 12-step group?

MR. GRIFFIN: Well, I don’t really talk about that specifically what program I got into. I know that’s kind of drawing a ridiculous line, but I acknowledge that I have broken my anonymity on a public level.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: And it just — I don’t say the words, and it’s almost like superstition.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. All right. That’s fine. Then I will honor that as kind of part of the mystery somehow. So you’ve written an analysis of desire is at the root of the compatibility between Buddhism and the Twelve Steps, talk to me about that.

MR. GRIFFIN: Well, it comes down to the Second Noble Truth in Buddhism. So the First Noble Truth is the truth of suffering, the unsatisfactoriness of life. And then the Buddhist says the cause of that is our desire, or our clinging, our craving. So he’s pointing at something that is exactly what addiction is about and it — the more I started to look at that the more I realized that really addiction wasn’t something outside the of normal human behavior, it was just an extreme case of exactly what the Buddha was saying was the cause of all our problems.

MS. TIPPETT: A magnification of that.

MR. GRIFFIN: Yeah, I mean, I talk about it as being a continuum of craving and attachment that in this sort of middle zone, we call it normal. And then when you get out to more the edges of that continuum, we call that addiction. But it’s essentially the same thing. In a way, the spirituality of recovery is that we get to see that so clearly.

MS. TIPPETT: Buddhist teacher and author Kevin Griffin. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Spirituality of Addiction and Recovery.”

In his book One Breath at a Time, Kevin Griffin describes the first three of the Twelve Steps as the surrender steps. Here again is the voice of Bill Wilson, recorded in 1963, summarizing these three steps that he helped lay out in the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous.

MR. BILL WILSON: (recording of the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous) “One, we admitted we were powerless over alcohol, that our lives had become unmanageable; two, came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity; three, made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.”

MS. TIPPETT: And what’s really fascinating to me as I read your work is how you — you live with — if I can put it this way with these different sacred texts, which is the teachings of the Buddha and the Big Book.

MR. GRIFFIN: Mm-hmm.

MS. TIPPETT: Something that I’m quite aware of is how there are some real problems with the language of the Twelve Steps in a modern Western imagination, right?

MR. GRIFFIN: You noticed that.

MS. TIPPETT: And well — and you know, and you talk about how Buddhist will sometime balk, but other people balk as well.

MR. GRIFFIN: Oh, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, just the basic in Step One, we admitted we were powerless. Twenty-first-century Americans don’t admit that they are powerless over anything.

MR. GRIFFIN: Yeah, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And you write and I think this is really part of it that’s for many of us now, I think powerlessness equals passivity or giving up, but that’s now how you’ve come to experience it.

MR. GRIFFIN: No, I think that anybody who sits down and closes their eyes and tries to follow their breath immediately sees that they are not in control of their mind and body. And if you want to call that powerless or just not in control, it doesn’t really matter so much.

MS. TIPPETT: And that is more palatable somehow: “not in control.”

MR. GRIFFIN: Yes, yeah it is, and I think that partly the language of the steps is meant to be dramatic—

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. GRIFFIN: —so they really get your attention, but I got to a point where I kind of just reflected on how what happened to me when alcohol got in my body. And what happened was that the craving overcame me. And sometime before it got in my body, the obsession overcame. And to say am I actually powerless, can I do nothing — no that’s not true. It’s not that I couldn’t do anything, it’s just that the force of energy is so strong in that direction that it’s unlikely that I will do anything. So it’s a problematic word in certain ways. Now, there’s the Buddhist teaching about sickness, old age, and death, something else that, you know, our—

MS. TIPPETT: Americans don’t —

MR. GRIFFIN: —culture doesn’t like to think about.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Don’t really accept.

MR. GRIFFIN: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, or even just the basic principle that suffering is a central experience of life. That’s not the way Americans describe life.

MR. GRIFFIN: Oh, yeah. Yeah, and suffering is the common translation of the word dukkha, which — as is true of many of the terms in Buddhism — our English translation doesn’t quite grasp it, so we have to use a variety of words. So unsatisfactoriness is actually kind of more accurate in a lot of ways, in the sense that there’s no moment at which you arrive at total satisfaction in your life. You have a moment of intense pleasure and then it’s gone. It doesn’t continue then, you know, it’s, as I like to say, after sex a cigarette, you know.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: I mean, you know, sex wasn’t enough? I mean my goodness.

MS. TIPPETT: You use also, this example of the tradition commercial at the end of the Super Bowl.

MR. GRIFFIN: Right. You’ve won the MVP award for the Super Bowl, and now, “I’m going to Disneyland.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: Like it wasn’t enough to reach the pinnacle of your profession, but in fact the only place to go after that is the place where dreams are made, you know, because you’ve already achieved everything in reality.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: I mean, it’s never enough. And that’s the real powerlessness of life, I think, you know, that it’s never enough. You never have what you want, and the fact is that that’s because desire tells you that once you satisfy it, you’ll be OK. And that’s just not true. It’s this lie that we keep believing. I mean, I also want to say, very quickly, that when we set up the idea that not having desires is the way to be happy, then we just create another goal and another way of beating ourselves up. ‘Oh, I’ve still got desire, what’s wrong with me?’ And, you know, desire is a natural human quality, you know, we wouldn’t survive if we didn’t have desire. So it’s — that’s what’s great to me about spiritual teachings is that when you get down to it, there’s always a paradox there. And it’s never just this, OK just do this and then, and then everything is OK. And that’s the argument that I have with fundamentalism, including fundamentalist Twelve Step.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: Which there is plenty of, and fundamentalist Buddhist. You know, there isn’t this one answer that satisfies us in every situation. That’s why we have to be mindful. That’s why we have to be awake.

MS. TIPPETT: And then of course the other language that comes into steps two and three of the Twelve Steps is about the higher power: “We came to believe that power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” And Step Three: “Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.” I think the language of higher power is again, as you said, it’s dramatic and it doesn’t quite seem to fit a modern imagination. But I wonder if it was especially challenging for you as a Buddhist?

MR. GRIFFIN: I don’t know, I don’t know, for me it’s about deepening and moving forward in my spiritual path, my spiritual growth. And so I think it’s more than the words. I think the words are pointing to the problem, which is that people loose their way, their sense of connectedness of surrender, you know, of being — I guess having faith or being OK, um, and trusting in the process. And the higher power — there’s a lot of ways we can talk about higher power, one of the main ways I talk about higher power is the law of cause and effect, also known as karma. So if you act in ways that are going to lead to more harmony and happiness in your life, you are going to have more of that. If you act in unskillful ways and immoral ways, you’re going to get those results. And when you turn your will in your life over it means that instead of following your own reactive self-centered, selfish, greedy mind, you are saying there is a better way to live. So for me, it’s not religious or even about God, although I do believe that what I call God includes karma and karma is a big part of what I call God.

MS. TIPPETT: Author and Buddhist teacher Kevin Griffin. He describes the fourth through ninth of the 12 steps of recovery as a stage of “investigation and responsibility.” This begins with Step Four, as the Big Book puts it, to make “a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.” Kevin Griffin says that his own process of taking a moral inventory back through his life also became an exercise in better understanding some of the core spiritual teachings of Buddhism.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, you talked about, when you were there going back through broken relationships and violence and recklessness and you wrote, “Each of these memories was like a slap in the face, an awakening to another view of the world.” And then you write, “This was slowly, painfully the beginning of compassion developing in me.” Now, explain that.

MR. GRIFFIN: So when we can admit deeply to our own failings, then we can start to potentially accept the failings of others, and that’s what I meant by that. That it’s harder to judge others when you’ve seen how your own weaknesses and the mistakes that you’ve made and really been honest about them. Then you can see someone else — instead of saying, ‘Oh, what an idiot,’ or worse language, saying ‘Oh, that’s really sad that they are doing that to themselves and that they are doing that to the world or to me even.’ Because they are creating this suffering for themselves and indeed they are expressing their own suffering. You know, I had a boss one time, who — I was driving magazine deliveries, and his bookkeeper was really an angry person and was really difficult to be around. And I remember saying to my boss one time, ‘Oh, he’s such a pain.’ You know what he said, ‘You know what I do, when I hear him talking like that, I think that’s the way he talks to himself. He’s walking around with that voice in his own head and then I feel compassion for him, rather than being angry with him.’ I thought that was a very wise thing.

MS. TIPPETT: That is very wise. It’s hard to live that way though.

MR. GRIFFIN: Well, of course, I mean, that’s why you have mindfulness to try to remind you the root of the word mindfulness — the word we translated mindfulness from: sati. The root of that word has to do with memory and, you know, I often say to people it’s easy to be mindful in a moment if you just remember to do it. The hard part is to remember to be mindful. Concentration, that’s difficult to sustain, mindfulness easy, you should know

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. GRIFFIN: To say, ‘Oh, be mindful. OK, yeah. All right. Here I am sitting in the studio I see the microphone, you know, here I am, I feel that.’ But how do I remember to do that all the time? That’s the hard part. So that’s why we practice, that’s what practice is all about, right, is to embed that habitual tendency to remember.

MS. TIPPETT: And this also does get at I think a hard question about — you talk about your experience and this is an experience many people have had of implementing this practice of seeing, seeing the destructive patterns of their own behavior and then in that act of seeing becoming aware, beginning to change, unraveling the habits. And yet we’re learning more about biological roots of addiction, we know more about mental illness and even just the stubbornness of human behavior that may have to do with how our neurons fire. I just, I wonder do you, do you believe, do you feel that most of us or all of us in some part of ourselves are capable of this kind change, or how do you wrestle with that?

MR. GRIFFIN: Hmm. Well, one day at a time

MS. TIPPETT: Hmmm.

MR. GRIFFIN: You know, and I’ll say that there are some things and they talk about this, I think Bill Wilson talks about this in The Twelve … and Twelve — there are some things that we can really change. And like I don’t have the obsession to drink any more or to take drugs. Occasionally, I might think it would be nice to have a cold beer, you know, but I don’t have the obsession anymore. So that has really been uprooted, but there are other things, as you say, that are perhaps, yeah, somehow more hardwired into us. Certainly, I mean, I think sex addiction is really, I mean, what a challenge, you know, that’s an energy that you have in you and you don’t just turn that off, you don’t just — I mean there’s nothing to put down. You know, you can’t just stop going to the liquor store.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: You know, it’s with in you, and the same with food addiction. I mean, people, who have food addiction, have to eat their drug of choice three times a day.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: You know, I mean what a challenge. So there’s two different ways we can look at this. There are things that change, that really do get uprooted, and then there’s things that we learn to live with. And living with, I mean, that’s the First Noble Truth, you know, that there’s suffering and that you don’t get to turn it off. And so it’s how we hold the experience, it’s how we live with it. I mean, that’s the grace of spiritual life, is how we live with our struggles, with our suffering. I mean, that’s why happiness is not about pleasure.

MS. TIPPETT: Kevin Griffin. Here again is the voice of AA co-founder Bill Wilson reading the final three of the Twelve Steps.

MR. BILL WILSON: (recording of the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous) “Ten, continue to take personal inventory, and when we were wrong promptly admitted it; eleven, sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for the knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out; twelve, having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.”

MS. TIPPETT: For you, as a Buddhist in recovery, there is this very intriguing echo between the real meaning of the name Buddha, which is to be awake, and then Bill Wilson several thousand years later is talking about spiritual awakening. It is very interesting to see you make that connection.

MR. GRIFFIN: Yeah, mean it’s one of the easy ones to make. It’s very clear isn’t it, um, and you know awake is a metaphor. So part of our work is to figure out what awake is and how I bring that about.

MS. TIPPETT: And the awakening, it comes at the end rather than at the beginning. I think in our culture we think you have this breakthrough and then everything flows from there. But this is, this is an awakening at the end of an incredible amount of hard work and really not at the end, because then the cycle starts all over again.

MR. GRIFFIN: Yeah, you know, there are different models about awakening and, you know, Jack Kornfield has that book After the Ecstasy, the Laundry, which is sort of the model you are talking about, you know, where you have this kind of breakthrough experience and then you kind of try to integrate that into your regular life. And the people have that. I haven’t, unfortunately.

MS. TIPPETT: You don’t do the laundry yet?

MR. GRIFFIN: No, I — yeah, I do the laundry, I don’t know about the ecstasy part

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. GRIFFIN: I>mean, I didn’t’ — I didn’t have a breakthrough experience is what I’m saying, and I have known people who’ve had these moments before they even started spiritual practice, where they had some kind of enlightenment experience or satori or whatever you call it. And ultimately the problem with having the big breakthrough moment is that it actually doesn’t solve anything. I was teaching this weekend and saying that, you know, right now as I’m teaching, I’m teaching you about things that I’m not experiencing right now. I’ve had the experience of them, you know, I’ve had these experiences of deep emptiness or stillness or tremendous sense of connectedness or ecstasy, but right now I’m just sharing about them and having had that experience I can refer back to it. And that’s the value of it actually that, you know, what I thought when I got involved with spiritual practice was I’m going to have this enlightenment experience and that’s just going to carry me. I’m going to float on that for the rest of my life, everything is going to be solved for me.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. GRIFFIN: But it really — it’s just a reference point. And if you forget that reference point, then you can just fall back into the same habits just as easily.

MS. TIPPETT: Let me just ask this I think by way of ending. What do you understand about Buddhism that you might not have understood or at least so deeply or richly without the Twelve Steps, and what do you understand about the Twelve Steps that you think you see more clearly because of your Buddhist practice?

MR. GRIFFIN: What I saw through my Twelve Step work was that isolated intensive meditation practice was not going to fix my life. The Twelve Step program has helped me to get my feet on the ground and see that what they call in Buddhism sila, the ethics, is the foundation the moral — the morality is the foundation of spiritual growth. I did not see that when I met Buddhism.

For the Twelve Steps, what I see is that Buddhist practices, especially, give me access to the spiritual experience the direct conscious contact that we’ve talk about. It’s not theoretical anymore. It’s not just saying a prayer or going to a meeting. It’s really having that authentic sense of touching something beyond yourself, something, you know, powerful and meaningful.

MS. TIPPETT: Kevin Griffin is a writer and meditation teacher. His book is One Breath at a Time: Buddhism and the Twelve Steps. Earlier in this hour, you heard author Susan Cheever. In closing, final words of Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill Wilson reading from the chapter called “How It Works,” in the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous. This was recorded for AA World Services in 1963.

MR. BILL WILSON: (recording of the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous) “Many of us exclaimed, ‘What an order. I can’t go through with it.’ Do not be discouraged no one among us has been able to maintain anything like perfect adherence to these principles. We are not saints. The point is that we are willing to grow along spiritual lines. The principles we have set down are guides to progress. We claim spiritual progress rather than spiritual perfection.”

MS. TIPPETT: In my unedited interview with Kevin Griffin, he delves in greater detail into Buddhist philosophy and the Twelve Steps. Download free MP3s of this program and all our unheard cuts at speakingoffaith.org.

And we’re providing more detailed insight into our production processes on SOF Observed, our staff blog. Preview audio of our upcoming program on Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. All this at speakingoffaith.org

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck, Shiraz Janjua, and Rob McGinley Myers, and with help from Alda Balthrop-Lewis. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with Web producer Andrew Dayton. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

[Announcements]

Next week, “Approaching Prayer” — with musician Anoushka Shankar, translator Stephen Mitchell, and theologian Roberta Bondi. Please join us for the next Speaking of Faith.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections