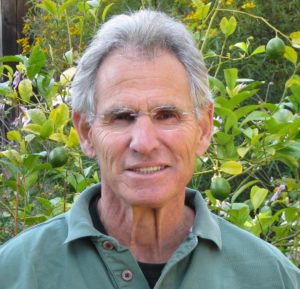

Jon Kabat-Zinn

Opening to Our Lives

Jon Kabat-Zinn has learned, through science and experience, about mindfulness as a way of life. This is wisdom with immediate relevance to the ordinary and extreme stresses of our time — from economic peril, to parenting, to life in a digital age.

Guest

Jon Kabat-Zinn is founding director of the Stress Reduction Clinic and the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. His books include Coming To Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness.

Transcript

December 27, 2012

MS. KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Jon Kabat-Zinn is a scientist, writer, and teacher who helped create the field of stress reduction. He’s clinically demonstrated the benefits of ancient traditions of mindfulness and meditation. And he’s adapted these for mainstream Western medicine and society — for people who are healthy or living with chronic illness, for Olympic athletes and corporate cultures. Jon Kabat-Zinn offers wise perspective on inhabiting the ordinary and extreme stresses of our lives. Technology may function 24/7, he points out; our minds and bodies do not. But he has practical and spiritual tools accessible to everyone — for slowing down time and “opening to our lives.”

MR. JON KABAT-ZINN: It doesn’t actually take any more time to say good-bye or hug you know, your children or whatever it is in the morning when you’re on your way to work. But the mind says, “I don’t have any time for this.” But actually that’s all you have time for, is this because there’s nothing else than this. So when your four-year-old can’t decide which dress she wants to wear, that’s not a problem for you, unless you make it a problem for you. That’s just the way four-year-olds are. And the more we can sort of learn these lessons the more we will not be in some sense running towards our death, but in a sense opening to our lives.

MS. TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. This is On Being, from APM, American Public Media.

MS. TIPPETT, HOST: Jon Kabat-Zinn is the founding director of the renowned Stress Reduction Clinic and the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He’s also gained a global audience with his books, including Full Catastrophe Living and Wherever You Go, There You Are. When I interviewed him in 2009, we focused in on my favorite book he’s written: Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness.

MS. TIPPETT: I’d like to start with you. You know I interview theologians and scientists and artists and physicians — all kinds of people. I always start the interview by asking whether there was a religious background to your life, to your childhood.

MR. JON KABAT-ZINN: Hmmm. Well I suppose there was some background that could be called religious. You know I was born into a family that ethnically Jewish but that didn’t practice at all. I was not bar mitzvahed and never set foot in synagogue until I was 13 and some of my friends from school were bar mitzvahed. So I was not brought up in the Jewish tradition.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: On the other hand, I grew up in New York City in Washington Heights in a very sort of diverse community in the late ’40s and early- to mid-50s. And mostly I played in the streets with kids who were Catholic and had their own ideas about Jews, and other faiths and so forth, and I didn’t take it personally because I didn’t identify with any of it. But as I got older, it had a very interesting texture to it, and I was certainly conscious of that growing up.

MS. TIPPETT: How and when did you start thinking about or did you discover meditation and mindfulness? How did that happen?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, sometimes I begin by saying that I was born into family where my father was a very highly recognized world-class molecular immunologist, and what was called in those days “immunochemist,” won lots of awards for his work, had a tremendous reputation — was a “scientist’s scientist” as many of his colleagues put it. Had one of his students win the Nobel Prize. And then my mother was as prolific as a painter as my father was in writing scientific papers and training graduate students and post-docs and so forth, but she was completely unrecognized. So I grew up in the classical C.P. Snow’s “two cultures”: the culture of science and the culture of art. And basically I was born into that. And so as a child I was, you know, it’s inevitable that you have your eyes open and are kind of taking the lay of the land. And some of it involved seeing these different ways of knowing the world, through the eyes of a painter and through the eyes, if you will, of a biological experimenter. And they are very different.

And so I think from a very, very early age on some level, long before I could actually articulate it, I was interested in the unity behind the divergences between those different ways of seeing epistemologies.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And that just developed as I got older, which is one reason why I was so interested in the arts as well as the sciences when I was in college, and the year that I spent at the lycée in Paris was like a renaissance year for me. So all of these threads — I mean, the reason I’m telling you this is that all of these were actually extremely germane to finding my way into the meditative practices and contemplative practices, because in a sense I realized in retrospect later that they were a potential path for unifying what …

MS. TIPPETT: I see.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … Wordsworth called “discordant elements.” That silence and reflection could actually tap into deep sources of understanding and wisdom that don’t come necessarily in the traditional ways to the intellect.

MS. TIPPETT: And then I think you’ve said that you actually started to meditate at MIT, right?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes, I did.

MS. TIPPETT: Which is such an interesting sentence.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: That in itself is kind of …

MS. TIPPETT: Especially 30 years ago or whatever, 35 years ago.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. And the story, which I wrote up in Coming to Our Senses in part, because I put a lot of my own personal story in Coming to Our Senses and some of it’s actually in various books, because I want people to understand that when they come to meditation that it doesn’t mean you give up being a person and you become some kind of, I don’t know, transparent weirdo of sorts. But that you change your relationship to who you think you are as a person and in particular to the story of who you are or think you are.

MS. TIPPETT: And it seems to me that you spend a fair amount of your time demystifying meditation and mindfulness, in fact, presenting it as you found it, as a spiritual technology that can be akin to some of the creativity and openness to experience that you love about science.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Oh, absolutely. And art. Yeah. In fact, I stay away from even the word spiritual. So it’s not so much that I’m into demystifying meditation, as it is, as I am into trying to make it so commonsensical to people that they will slap the side of their head and say, “Well, of course. Why the here didn’t I know that like 30 years ago?”

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: “That makes total sense.”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Because it’s often freighted, even the word “meditation” is freighted with so much cultural baggage and so much, really ideological baggage and sort of belief baggage that the essential beauty of it is often really not apparent to people until long after they have somehow wandered into the domain of it. And my feeling was if what the Buddha said was true and that this is a path that potentially leads to the freedom from suffering and if everybody on the planet is basically suffering, why shouldn’t it be accessible to virtually everybody on the planet as opposed to those people who self-identify as, say, Buddhists or as, you know, yogis or people who are into this or that?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And so I tried to create a kind of glide path into meditation that would be so commonsensical and accessible and based on what people really need and also fear and are challenged by, that we could at least empirically test whether, if it was framed in that kind of way, regular mainstream Americans would take to meditation. And, in fact, I think the proof after 30 years is pretty much in the pudding that we do.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. So let’s do that. Let’s talk about what you know as common-sense wisdom and let’s talk about it in the context of our culture right now where there’s a lot of stress …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: OK.

MS. TIPPETT: … and there’s perhaps a heightened awareness that we haven’t been as mindful or aware.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And so it’s a moment of interesting positive possibilities as well. So we’ve been talking to a number of people for this project we’re calling Repossessing Virtue, and one of the people we called up was Sharon Salzburg, who’s been on the program before.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m sure you know her.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. We’re close friends.

MS. TIPPETT: One of the things that’s clear to me as the economy started falling apart is the trust we had placed in the things that we assumed were logical and rational and in fact were highly irrational.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: So Sharon Salzburg makes a comment that in fact is so much more reality-based than our economic expectations and behavior for the last few years. She said, you know, as a Buddhist, “Change and suffering are inevitable parts of life.” And that’s something we kind of forgot in these boom years, and we are so shocked that things could change. Talk to me about what we’ve been doing as you understand that, both through the science that you do and the work that you do on stress.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: How you pay attention in your life actually can change your life and your biology and your brain.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: So when you don’t have any cause to question what’s going on, as you were suggesting in quoting from Sharon, and things are going in a direction that you describe for yourself as desirable — in other words, your 401(k) is increasing in value every year and so forth — it just seems like, yes, all is right with the world. And you can pay your mortgage payments and maybe buy a bigger house and on and on and on that this is the way it’s supposed to be. And we tell ourselves that this is the way it’s supposed to be. And then there are these rude awakenings that happen sometimes. It doesn’t have to be the collapse of the economy or the stock market. It can be as simple as, you know, something happening to one of your family members or yourself.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. She said the phone rings, you pick up the phone and you have some news about an illness …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And your whole life is different.

MS. TIPPETT: … and your whole life is different. Yeah.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. Whether somebody died or it’s a cancer diagnosis or whatever it is. But we live in a kind of somnambulant expectation that everything will go on the way it is. Do you know what I’m saying? And that is certifiably absurd. And so that, the stress if we loop it back to stress and the whole thing about mindfulness-based stress reduction, is that the stress really has to do with wanting things to stay the same when they are inevitably going to change. The law of impermanence basically rules the universe and so things are never constant; they’re continually changing. And if you want to hold them a particular way, you can do it for short periods of time at tremendous cost, but ultimately things change.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And if you don’t recognize that, then you’re going to create a lot of suffering for yourself and other people.

MS. TIPPETT: On our website, you can find that interview I mentioned to Jon Kabat-Zinn with Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzburg in our Repossessing Virtue series. That’s at onbeing.org.I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, exploring wisdom for living in a world of change with scientist and writer Jon Kabat-Zinn.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Mindfulness is not about thought, right? I mean, your book …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: … your very beautiful …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Oh, you mean the word “mindfulness” sounds like it’s about thought.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. It sounds like it’s about thought.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Good point.

MS. TIPPETT: Meditation, I think the stereotype is it’s about sitting …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Thinking.

MS. TIPPETT: … in your head.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: Your beautiful long book that you wrote just a couple of years, you know, Coming to Our Senses, and you even pointed out that for the Buddha the mind is also a sense and it is all about being embodied.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Exactly. Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: So talk to me about that and how that can make a difference in a moment like this where the world around us is so frightening.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, we really haven’t been educated to realize that there’s a certain faculty that we’re born with that is at least as powerful as any of the other faculties that we think about or know that we have, like the ability to think. We have never been trained in the ability to pay attention, for instance. We get yelled at in school for not paying attention …

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … or when the teacher thinks we’re not paying attention. Actually, we are paying attention, it’s just to something other than what’s on the blackboard or whatever. So attention and awareness are deep interior human capacities that never get any training or airtime or attention. What gets all the attention is thinking. And so when you begin to cultivate intimacy with these other capacities, it actually balances out our remarkable capacity for thinking and also for imagination and creativity. A lot of the creativity comes out of the stillness of awareness in not knowing. So rather than just sort of keeping tabs of what we know, it’s really helpful to be aware of how much we don’t know. And when we know what we don’t know, well, then that’s the cutting edge of which all science unfolds.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. You’ve also said that scientists make the best meditators.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Because they’re comfortable with that idea of wanting to know what they don’t know.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: But, you see, it’s all a question of thinking. I mean, the word “mindfulness,” for instance, I completely agree with you: Anybody who is naive to hearing it is going to think, “Oh, yeah. That’s some kind of cognitive manipulation.”

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: So I like to point out that in all Asian languages — at least I’ve been told this; I don’t know all Asian languages — but in all Asian languages the word for “mind” and the word for “heart” are the same word.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: So when you hear the word “mindfulness,” if you’re not in some sense automatically hearing the word “heartfulness” you’re misunderstanding it. And mindfulness in any event is not a concept; it’s a way of being. And it’s a way of being awake. It’s not a big deal; it’s just that we’re never taught that this is part of the human repertoire. So what does wakefulness mean? It means resting in a kind of awareness that is so stable that it’s not thrown off by the comings and goings of events within the field of awareness. So that you lose your balance when things go this way and things go that way, but you actually stay grounded when things go your way, as we put it.

And when things don’t go your way, it doesn’t mean that you have to rocket yourself or spiral into depression and hopelessness and a sense of despair. But very often if we take it personally and we feel like our successes say that we’re a good person and then, by extrapolation, our failures say that there’s something wrong with me, that I’m no good. And both of those are wrong. What goes up also comes down, whether we’re talking about the stock market or a ball that you throw up in the air. And if you mistake what you think of as the reality for the reality, then you’re going to suffer because you’re attaching the story of me, myself, and my successes and my failures to something that’s actually quite impersonal.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve come to think of meditation and mindfulness and yoga as spiritual technologies that these traditions have mined and kept alive and deepened. And as you say, they don’t just present themselves in the modern world to Buddhists. They present themselves as keys to sane living.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: And yet, you know, I’ve wanted to ask this question to someone for a long time. It seems to me you might be the correct person to ask. I mean, the Buddha left his wife and child behind …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Oh, I’m so glad you brought that up.

MS. TIPPETT: … and devoted himself utterly to this pursuit of enlightenment. Monastics — a lot of the studies — I don’t know how much you’ve been involved in these, but studies that I know you’re associated with where …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … they’ve studied stress on the brain and they’ve studied monastics and they find that they really change their minds. But, you know, they don’t pay the rent. They don’t live in fear of being laid off.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Absolutely right. Absolutely right. They are renunciates in a certain way.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: They’ve renounced the conventional world. But anybody who thinks that’s easy should try it for a bit.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And they find there’s as much stress on that side as there is on any other side. Greed, hatred, and delusion are equal opportunity employers.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: So just thinking of yourself as a spiritual person or renouncing the world, easier said than done. But that said, your point is very well taken and so the real challenge is how do we do it living in this world?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Without having to sort of abandon wife and children or husband and child or whatever and going off for the sake of our own small-minded, if you will, enlightenment? One of the things — I don’t know if you know this, but my wife and I wrote a book on mindful parenting …

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, I do. Yeah.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … about 12 years ago. And one of the things that we say in there is of all the spiritual practices, you know, no matter how severe the monastery and how arduous the particular practices associated with it, living with children is probably the most powerful spiritual practice that anybody could ever be engaged in if you open yourself to it that way. I like to look at them as when they’re little as little living Zen masters that are sort of parachuted into our lives to push all our buttons and see how we’re going to work with the challenges they throw at us in addition to, of course, having to put food on the table, pay the rent, build a career, have a loving relationship, you know …

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … that is sustained over time and isn’t merely mechanical or perfunctory. And this is like a really tall order. So I really think that in some way this is the best monastery. It’s not a conventional monastery, but, you know, this is the perfect environment in which to cultivate mindfulness and liberative, you know, clarity, wisdom, compassion, working with the tools at our disposal. Rather than thinking, “I’ll leave my family and go off and be in a cave and get enlightened and then I’ll come back and rescue everybody.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Jon Kabat-Zinn teaches and speaks widely. Here he is leading an introductory meditative experience at Google’s corporate headquarters in Mountain View, California, in 2007.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: OK. So what we know. We have a body, relatively speaking, and we’re here now. So let’s see if we can tune into now for no other reason than just for fun. OK? Just not to get anywhere, to be more relaxed, to become a great meditator, to break through, you know, some problems that you’re having, whatever it is, but to just see if you can hold this moment in awareness. You don’t even have to shift your posture; you just hold this moment in awareness.

Now, there’s a lot going on because, as I said, even if we limited it to five senses — if your eyes are open, they’re seeing. Your ears you can’t close so there’s hearing. OK? Nose you can’t close so there’s some kind of sensing going on through the nose, some aroma of rug and wall. There is whatever the sensations are in the mouth. And there is the contact of the back with the back of the chair and your butt with the chair and if you’re on the floor, you know. Let’s see — and there’s, of course, one aspect appropriate perception which is, interestingly enough, without any of it on our part — thank god, because otherwise we would’ve died long ago for just, like, forgetting, getting distracted — we’re breathing. So see if you can just feel yourself breathing.

So if the mind wanders you know what’s on your mind and bring it back. If it wanders 10,000 times you know what’s on your mind 10,000 times. And without judging, condemning, forcing, blaming, just come back to this moment, this breath. Each breath a new beginning. Each out breath a complete letting go. And, voilà, here you are again right here. No agenda. Just this moment. Just this breath. Just this sitting here. Outside of time, if you will.

MS. TIPPETT: The term that is used with kind of what you’ve brought to medicine — you and others — is the mind/body connection, the mind/body interface. But really that’s not quite big enough, is it? I mean, it still sounds like they’re two different things.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: See, again, there’s this kind of paradox when you use a term like “awareness,” which again sounds like a mental activity, but what you ask people to do and how they become aware is to drop into their bodies and their senses.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. Drop into being. See, we call ourselves human beings. That’s a big cliché, but we’re more like human doings.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: So we actually haven’t had that much experience in inhabiting our own being. It’s kind of almost foreign territory. And as soon as we do, we want to fill it up with something, even if it’s, say, looking at a sunset. And then you’ve got to talk about it instantly, “Oh, you’re seeing this. Is it as beautiful as I think it is?”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And all of sudden, you’re not seeing the sunset anymore; you’re in your thoughts about the sunset. So whatever it is, our thoughts very often wind up carrying us away from the heart of the matter. And what these, as you put it, technologies or intra-psychic technologies, whatever you want to call them, offer us is a chance to continually return to what’s deepest and best in ourselves. And it’s not something you have to get by going to Harvard or working in the vineyards for 20 years; you’ve already got it.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And the body is a big part of it. And so the practice of mindfulness, whether you’re doing it in some formal way, meditating in a sitting posture or lying down doing a body scan or doing mindful hatha yoga, but the real practice is living your life as it if really mattered from moment to moment. The real practice is life itself. And coming to all of those senses in hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, touching, and also we could say minding. Which is another way of saying awareness-ing. OK? And it puts us in touch with a whole different dimension than thinking. There’s nothing wrong with thinking.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: It can be incredibly creative and it can also be incredibly destructive. But awareness can’t be destructive.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a place in your book where you just really put a fine point on what’s at stake. You know, that any moment in which we’re not aware, any moment that we’re not attentive to, is lost. I mean, and there’s a …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. You’ve abandoned your own life.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. There’s a quote you have from Thoreau in Walden, “Only that day dawns to which we are awake.”

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … to which we are awake. “Only that day dawns to which we are awake.” It’s the third-to-the-last line in the whole book of Walden. And, you know, this is a realization that he had, that you can — and this was even in the 1840s in Concord, which we might think of as idyllic. You know, he was describing the residents of Concord and the farmers as living lives of quiet desperation.

So it’s not just the email and the Internet, you know, and the World Wide Web that are carrying ourselves away from ourselves. This is something …

MS. TIPPETT: It’s the human condition.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah. It’s the human condition.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: But I like to point out, if we have a moment for this, Krista, is that we call ourselves homo sapien sapiens. That’s the species name we’ve given ourselves. And that means from the Latin sapere, which means “to taste” or “to know.” The species that knows and knows that it knows. So that means really awareness and meta-awareness. And it would be nice if that were actually true, but I think it’s a little premature to call ourselves that. And now maybe we need to live ourselves into owning that name by cultivating awareness and awareness of awareness itself and let that be in some sense the guide as to what we’re going to invest in, how we’re going to make decisions about where we live, where we’re going to send our kids to school, how we’re going to be at the dinner table. Whether we’re going to take our bodies and our children and our parents for granted or whether we’re going to live life as if it really mattered moment by moment.

And that’s not some kind of prescription for more stuff that you need to do in order to be happy. This is getting out of your own way long enough to realize that you already have the potential for tremendous well-being and happiness right here, right now. Nothing else has to change.

One thing it does is it really slows down time. When you’re in the present moment, time really stops.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, that’s interesting, because time is something none of us have enough of now, isn’t it?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Exactly. Just take an example: in the morning when you’re on the way to work. It doesn’t actually take any more time to make eye contact or say good-bye or hug your children or whatever it is, but we often feel so rushed that we’re blasted out of the house.

MS. TIPPETT: I was going to say, I’ve been yelling at my children for 10 minutes to get in the car.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: “Good-bye. I’m out of here.” Or yell at them to get in the car.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m not sure they want me to make eye contact.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, exactly. And so we’re so stressed that we’re stressing out the children or whatever it is. But it actually — and the mind says, “I don’t have any time. I don’t have any time. I don’t have any time for this.” But actually that’s all you have time for, is this because there’s nothing else than this. So when your four-year-old can’t decide which dress she wants to wear that’s not a problem for you unless you make it a problem for you. That’s just the way four-year-olds are.

And the more we can sort of learn these lessons the more we will not be in some sense running towards our death, but in a sense opening to our lives. And there’s a huge distinction between the two. And all the scientific evidence is suggesting that when you choose life in the way I’m talking about, your brain changes in both form and function, your immune system changes, your body changes. I mean, we start to really take care of what’s most important and there are very, very tangible results at the level of the body, the mind, and the heart, and most importantly our relationships with the world and with our loved ones and with our own bodies.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Watch Jon Kabat-Zinn’s fascinating talk at Google headquarters on our blog at onbeing.org. While you’re there, you can listen to this show again. Also, find directions to subscribe to our podcast in iTunes and download it to your mobile device for easy listening while exercising or driving in your car.

And, check out our 10 most popular blog posts and podcasts of 2012. If you’ve missed any of these shows, here’s your chance to catch up with the best of the best — as chosen by you. That’s on our blog, again, onbeing.org.

You can also keep in touch with us at facebook.com/onbeing. Follow the show on Twitter @beingtweets. Follow me @kristatippett.

Coming up, Jon Kabat-Zinn on the practical and spiritual implications of having Stone Age minds and bodies in a digital world.

I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from APM, American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today I’m with scientist and writer Jon Kabat-Zinn. He’s helped bring mindfulness-based stress reduction into mainstream medicine and society from people living with chronic illness to Olympic athletes to corporate boardrooms. We’re exploring what he’s learned through science and life, about mindfulness in the face of the ordinary and extreme stresses of our time.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve been saying some very interesting things about the digital revolution. That we are saddled with a Stone Age mind in a digital world, and that has huge repercussions. Something interesting to me as I talk to people about taking stock of some of the larger implications of what’s gone wrong in our economy and how we want to live differently beyond this is people saying, “I need to take control of technology.” Not that technology is a bad thing, but that somehow we feel that it has taken over.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: What are you thinking about that?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, I’m struggling with it like everybody else.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: I mean, we’re the guinea pig generation.

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean by that?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, in my lifetime there was only the analog world and now at a certain point, in the late ’90s I think, you know, really for most of us, it became digital with the World Wide Web and, you know, all of that. So this is a gigantic experiment. It’s never happened before on the planet. Everybody that’s born more recently they’ve only experienced the digital world …

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … not the analog world, as least talking about our country. So we do, I agree with you. I think we need to let that be in some sense an object of attention. We need to hold that in awareness and see how much the technology is improving our lives versus how much the technology is turning us into slaves of the technology, which it is certainly doing in a certain way. Because the technology is seductive. I don’t know if you’ve noticed that, but it can be very seductive. And addictive. And after a while, between BlackBerrys and pagers and laptops and this and that, first of all, just let’s consider what we used to quaintly call the “workweek.”

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: There’s no end to the workweek.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: There’s no beginning to it. There’s no end to the workday or beginning of the workday. So we can work 24/7 everywhere. IBM brags about this in their advertisements. When IBM goes digital, the workplace is everywhere. Yeah. Great. Except that life isn’t merely working.

MS. TIPPETT: Technology makes this 24/7 reality possible but, in fact, our bodies — just our bodies, but our bodies and our minds and our spirits aren’t designed …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Exactly. They are analog.

MS. TIPPETT: … to do 24/7.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: That’s what I meant by a Stone Age body.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And the Stone Age mind in a Space Age world. So we’re in transition here, and I’m not knocking the technology.

MS. TIPPETT: No.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: I’m not saying sort of like we should go back — I’m not taking a Luddite position on this. I think that technology is incredibly beautiful, and it’s going to get more and more and more powerful and more and more beautiful. But there are issues associated with it that have to do with — the technology is in some sense getting more sophisticated than our understanding of ourselves as human beings …

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … without the technology. And what I’m saying is that the technology is going to wind up changing us as human beings. And people talk about, like, what the future of this technology is when things will be so small that actually your computers, you’ll swallow it and it will do things inside. Like, you know, you’ll swallow your doctor or whatever, and they’ll fix you from the inside.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Or, you know, nanotechnology and all of that kind of stuff and then robotics. You know, we’re moving towards a very strange world in some ways, at least so far that we don’t know what it’s going to be. But one piece of it hasn’t developed yet and that is our intimacy, our deep understanding of what it means to be human. We’re still in our infancy as a human species. And before we start to talk about wet/dry interfaces where you start putting chips inside of the skull, for instance, to regulate certain things or upgrade our memory or whatever it is that might seem so attractive, that we really in the next few generations need to reclaim the full dimensionality of our humanity. My point is that maybe the technology will be a kind of mirror in which we can look and remind ourselves that there are aspects of being human and being analog that we don’t want to give up to machines when they get smart enough to maybe pretend that they have feelings or look like they have feelings.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Or they’re so bloody faster at calculations and computations than we are that we begin to feel insecure or inadequate in the face of our computers.

MS. TIPPETT: When you talk about it this way, you know, when you talk about us being the first generation and being in kind of in an experiment, it brings me back to just a core Buddhist insight, that we have to have a compassionate relationship with those things that are difficult, right, with our fear.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: But also I’m thinking with the stress that this moment of rapid change, this new territory, creates just by virtue of being new territory.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Absolutely. Absolutely. And, you know, this is far too serious a matter to take too seriously. So it really has to be leavened with humor and a sense of humor.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. That’s good.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Really. I mean, it’s an ongoing engagement, so to speak. And since it’s happening in a sense I think all of us to whatever degree and each in our unique way are being called upon to find out who we are and to live that authentically in the service of this world not just for our own particular small-minded gain or benefit. And I see that happening, you know, on a very, very vast scale. Obviously, nobody can understand fully what’s going on at the moment, but the very idea that mindfulness would be of interest now as broadly as it is in the society, and that the number of papers with the word “mindfulness” in the title in the scientific literature is going exponential, and the amount of funding that is funding research in mindfulness at the NIH is going exponential, and the fact that it’s now …

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And the fact that medical education is training to encompass this.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: It’s also being brought into the military. It’s being brought into business. It’s being brought into professional sports. I mean, from the perspective of 30 years ago, this is basically inconceivable. And yet, it’s already happened. And I think it’s part of a much larger phenomenon from where maybe as a species, because of all the crises we’re facing, we are in some sense tapping into that deep human capacity for waking up at the last moment and doing something right.

MS. TIPPETT: And these resources that in fact have been cultivated in places for thousands of years.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Exactly. And learning how to tap into them in a big way.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, Jon Kabat-Zinn’s science of mindfulness.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I was having a conversation with someone who is involved in the field of neuroeconomics. Have you heard of that?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Mm-hmm. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. And one of the things they talk about is that there is a natural human inclination to empathy, but one of the things that dampens that is stress. I mean, they can see that happening in the brain.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Right. And they can run different scenarios and really stress people out and see how they behave.

MS. TIPPETT: And I kind of connected some dots, and I don’t know if this is just me, but I think one of the questions we’re asking ourselves in this culture right now is it seems like all along the line, not just in the top levels of finance, but all along the way, people were making decisions that were irresponsible …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … to themselves or to others. You know, mortgage lenders.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes. Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: And it made me wonder if one of the consequences of the rapid technological advance just of the last 10 years is this 24/7 reality, which is very stressful for us as human beings and that …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: … possibly just that had this very real and devastating implication of being — of making us make less moral decisions and then real economic consequences. And in that sense …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, I think you may have something there. I mean, I still think that actually greed played a huge role in it, that it was just like free money …

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: … and wasn’t so stressful. I mean, they were creating stress down the road for other people, but not so much for themselves. Yes, they are leading a stressful life, but it can also be — and this is one of the dangers and why it’s so addictive — is it’s intoxicating. You begin to feel powerful, sometimes extremely powerful because you can make so many decisions in such a rapid sequence and then see almost immediately the positive consequences of them for yourself.

And it’s the kind of thing where you really can get addicted to it. And I think then you lose all sense of moral judgment, compassion, even just clarity and become sort of entrained into a mind state that really is deluded. So the real challenge here is, as you posed it at the beginning, are we going to learn something that’s going to really set us on another path or will it just be another recycle of the same old, same old?

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And I think that’s a big question, isn’t it?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: It is.

MS. TIPPETT: And I suppose that’s where these kinds of …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: But that’s where mindful leadership, you see, comes in. It’s like you say Obama seems like a much more mindful president than any president that we’ve had so far, at least that I’ve had exposure to.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. That’s interesting, isn’t it?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And so who knows what that will mean? I mean, mindful doesn’t necessarily mean perfect. Doesn’t even necessarily mean great. It just means that there’s some degree of awareness and sort of a deep understanding of interconnectedness that is dealing with …

MS. TIPPETT: And emotional intelligence.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: And emotional intelligence that is, in fact, being brought to bear on these very, very intractable problems. That once the system gets into this kind of atrial fibrillation, it’s very, very hard to get it stabilized.

MS. TIPPETT: Let me ask you this. You’ve talked about this kind of thing and worked on the basics of mindfulness at places like Google or MIT, you worked with the U.S. rowing team, Congressional staff, other businesses. I loved something you said at Google, that the key to creativity is cultivating more spaciousness in the mind.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, actually, the spaciousness is already in the mind. We can’t cultivate it. What we can cultivate is intimacy with it so that we actually know how spacious and how luminous and how creative and how reliable our own minds are. Now that’d be good to start learning in kindergarten.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: You had your scientist father and your painter mother.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And somehow you feel that the perceived disconnect or the differences in them made you want to reconcile and maybe made you more open to something like mindfulness. You know, you said at the beginning that being a scientist and being a painter don’t have much in common, but in fact at some very deep levels they do have very intriguing …

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Oh, absolutely. I wasn’t saying they didn’t have much in common.

MS. TIPPETT: No.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: I’m just saying they speak different languages.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. But when you find those intriguing echoes between those kinds of pursuits.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Yes. Then you find the unity.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. How would you talk at this point about that, about that unity, what that looks like?

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Well, perhaps rather than talk about it in a cognitive way, I’ll give you a couple of lines of poetry from Derek Walcott and leave it at that.

MS. TIPPETT: All right.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: Because it’s, I think, better to point to it rather than to try to make some definitive prose statement about it which is bound to be inadequate and incomplete. So Derek Walcott is a Nobel laureate from the island of St. Lucia, a Nobel laureate in literature. One of my favorite poems of his is called “Love After Love,” and I’ll just give it to you if it’s OK.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. Please.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: It’s not very long, but it really hinges around just this issue of who we are and how much we split ourselves apart.

“The time will come,” he says, “the time will come when with elation you’ll greet yourself arriving at your own door, in your own mirror, and each will smile at the other’s welcome and say, Sit here. Eat. You will love again the stranger who was yourself. Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart to yourself, to the stranger who has loved you all your life, whom you have ignored for another, who knows you by heart. Take down the love letters from the bookshelf, the photographs, the desperate notes. Peel your own image from the mirror. Sit. Feast on your life.”

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: When you podcast this show on iTunes, you’ll also find a special download of that reading by Jon Kabat-Zinn, of Derek Walcott’s “Love after Love.”

Jon Kabat-Zinn is the founding director of the Stress Reduction Clinic and the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. His books include Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness and Mindfulness for Beginners.

Here in closing is an excerpt from a presentation he made at MIT in 2006. There in 1966, as he likes to tell it, he began to meditate against the backdrop of the Vietnam War. He’s returned several times in recent years, including once with the Dalai Lama for a conversation with scientists from various disciplines on investigating the mind.

MR. KABAT-ZINN: We call ourselves homo sapien sapiens, which means “to taste,” to sense,” or “to know.” This is one of, I think, the great tragedies of our species so far is that so much beauty, science, art, music, poetry comes out of the human mind. And so much mayhem comes out of the same human mind, same human heart. In a sense — because in some sense we don’t know how to run the apparatus that we’ve been given and sometimes it takes over. And on good days just blinds us and we sort of make mistakes. On bad days, it blinds us to other people’s pain, and we can create an enormous amount of pain in the world out of our own pain and of our own ignorance and out of our own ambitious greediness, I guess I’d call it, to want things to be different “so that I will feel better.” If we’re not careful, we wind up with the kind of conceit that we are the center of the universe. It’s an occupational hazard of being packaged in a body, that the whole universe is outside and you are obviously the center of it, and you relate to it through all your senses, including potentially this capacity for knowing. That, to me, is kind of a working definition of meditation.

What is meditation? It’s not necessarily stopping in the kind of usual way that we would think of stopping. Stopping is good and, of course, we’re all going to be stopped, sooner or later the ultimate stop. We work a lot with medical patients who have tremendous suffering. Our track record with the dead is not so good. [Laughter] So one of the sort of cardinal rules of thumb is that as long as you’re breathing, no matter what’s wrong with you, from our perspective, there’s more right with you than wrong with you.

But can we learn how to pour some energy into what’s already OK with us? Which you could call health in the most profound of ways, our own interface with not only the outer world but also the interior world of our own thoughts, our own emotions, our own sensory experience, in ways that would actually have some degree of balance, some degree of interrelationality, because all the senses are actually interrelational. And so, while you’re the center of the universe, OK, so is everybody else. So is everybody else. So that means in a sense there’s no center. Cosmologists know this. Topologists know this. There’s no center and there’s no periphery.

But the question is what if we were to take the name we gave our species seriously and actually train to familiarize ourselves with the full perspective, the full dimensionality of what it means to be really human? For learning, for growing, healing, and for that matter, transformation across the whole lifespan.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if you’re hearing the same echoes I am — between Jon Kabat-Zinn and our recent shows with MIT’s Sherry Turkle and the evolutionary spirituality of Teilhard de Chardin — a new desire we seem to have to reflect on our lives with and beyond technology.

You can listen, download, and share all of these shows through our podcast page on iTunes or at onbeing.org. We will keep this conversation going on the radio and in those digital spaces that are so stressing and enriching us these days.

I’m doing lot of reflecting and sharing of ideas and articles on Twitter. Follow that @kristatippett. Follow all things On Being @beingtweets.

On Being on air and online is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, Susan Leem, and Stefni Bell.

Special thanks for this program to Farrar, Straus & Giroux for permission to broadcast Derek Walcott’s poem “Love After Love,” as published in his Collected Poems 1948–1984.

Our senior producer is Dave McGuire. Trent Gilliss is our senior editor. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections